Introduction

There are many memorial museums constructed on sites of violence, concentration camps from the Holocaust; Tuol Sleng, a school converted into a prison under Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge; prison used as sites for torture and murder under Argentina’s military rule – and many more. The Ethiopian Army’s use of the Tigrayan memorial museum as a prison and torture site is the first example we are aware of where a memorial museum, dedicated to documenting past violence, was converted into a site for new violence.

Located in the heart of Mekelle, the Tigray Martyrs Memorial Museum (TMMM) was constructed as a tribute to those who died in Ethiopia’s past conflicts, particularly people who fought with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) against Ethiopia’s military regime, the Derg, which ruled from 1974 to 1991. Dominating the exterior is a towering memorial and statues depicting the rise of the TPLF’s rise. The TMMM is mandated to preserve, promote and educate the history of the people of Tigray.

The extensive campus includes meeting spaces, a library, and the museum itself, set amid gardens and lawn, which provide a place for reflection and remembrance. The museum exhibitions focused on the social and political role of the TPLF alongside the war story: their communications, humanitarian programs, educational work, political debates, agricultural developments, cooking, conferences, and health programs appeared between scenes of military units. The development of the party, the armed movement, and the nation were interwoven as a single story. This was a “people’s war,” the narrative asserts: military strategy included social and political development.

The center began construction in 1992 [1984, Ethiopian calendar], one year after the TPLF defeated the Derg. The museum was officially established in 2008 [2001, Ethiopian calendar], governed by the Board of Trustees and approved by the Council of the State of Tigray under Proclamation No. 160/2001.

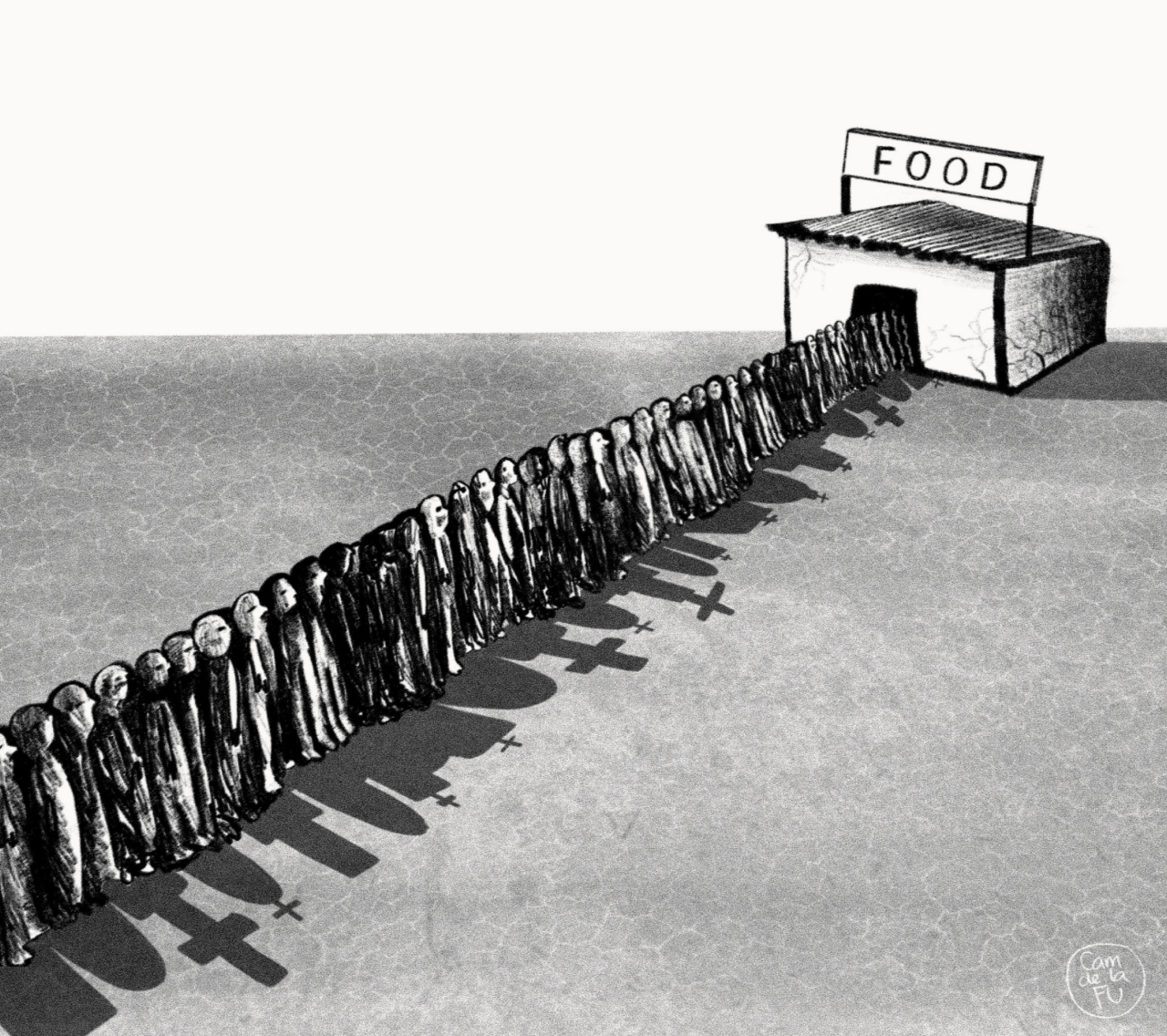

War returned to Tigray in 2020 – 2022, when the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF), aided by soldiers from Eritrea and Amharic militia, fought against Tigrayan Defense Forces (TDF). The ENDF stationed soldiers at the museum. They destroyed much of the museum and used the site as a temporary detention center for captured Tigrayan civilians, many of whom were tortured and suffered sexual violence.

To provide a deeper understanding of what occurred during the ENDF’s occupation of the museum, on October 8, 2024, we interviewed Yemane Gebrehiwot, a curator and program coordinator at the museum, who was among the first people to re-enter the museum after ENDF soldiers left.

This interview by jointly conducted by Birhan Gebrekirstos Mezgbo and Bridget Conley. Photographs of the TMMM, including some from 2017, during peacetime, and many documenting evidence of violence perpetrated by the ENDF during the occupation are available at this gallery.

Question

Can you tell us about when the museum opened and what its mission is?

Yemane:

The museum was established in 2001 in Ethiopia calendar, or 2009 in the western calendar. Its purpose is to preserve, educate and promote understanding of the 17-year struggle against the Derg regime, and it commemorates the freedom fighters. As you know, during the 17-year Civil War in Ethiopia to remove the Derg regime, we lost over 60,000 freedom fighters. After the overthrow of the Derg regime in 1991, the Tigray government established this center as a museum to honor the fighters who lost their lives for freedom and to represent the entire community. The freedom struggle was not only for the Tigrayan people, but for all Ethiopian nations and nationalities. The museum was built by the active participation of Tigrayan community, including those in the diaspora and from local farmers—each household contributed to its establishment.

The center includes various components, like the museum exhibitions, artwork that reflects the story of martyrs, and a large monument with different figures representing the struggle. The museum displays photographs, armaments, and books that were used during the struggle, including political and educational materials. As you know, during the Tigrayan Peoples Liberation Front’s [TPLF] struggle, there were different departments, such as the Department of Education for the local community located at the liberated areas and for the freedom fighters join the struggle, the Political Department that was the mastermind of the struggle by crafting the political ideology of the struggle, the Economic Department, which worked to empower the community economically, Public relation department and other activities that plays crucial role for success. The main goal of the museum is to represent the journey of the struggle and preserve the history to pass on to the next generation. Because of this, our collection includes of documents, pictures of the fighters (including women), artifacts, communication materials like radios, and old uniforms. As a museum expert, I, along with my colleagues, analyze this history, explain the details about the museum to both local and international visitors, and assist those who wish to study and research the period and sacrifices made for justice and freedom by the Tigrayan people.

Question:

Moving now into the period of the recent war. When did military forces take over the museum? And I wonder if you could also say which military forces occupied the museum?

Yemane:

Yes, the war started on November 4, 2020, and after around 19 to 20 days, the Ethiopian army besieged Mekelle. On November 28, Mekelle fell under the control of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces [ENDF], which took control of the museum on the first day, as controlling major institutions was their primary target from the beginning.

Question:

During the time they were there, did you hear any stories about what was going on, or did you know anything about what they were doing at the museum?

Yemane:

After they occupied the museum, they suspended all the civil servants, and no one had the right to enter. It was used as a central military command for eight months. During that time, we had no idea what was happening inside, but people living around the area observed various burning activities. They could tell from the smoke in the air. They also occasionally heard gunshots. However, we had no detailed information, neither as staff of the office or as simply as members of the community

Question:

When were you able to go back to the museum?

Yemane:

After eight months of occupation, on June 28, Mekelle was controlled by the Tigrayan military [Tigrayan Defense Forces, TDF]. The ENDF evacuated the city, and after that, we entered the compound. It was very disturbing. There was so much destruction and other unsettling scenes inside, making it clear that many troubling activities had occurred there [see evidence in the photogallery]. People from every part of the city rushed to see what had happened to the museum, as they were anxious about losing their preserved history and a vital part of their communal identity. And I also observe days after the withdrawal of the ENDF from the museum, visits to the museum by local communities, religious leaders, government officials and other interested individuals increased as they came to observe the situation. Witnessing the actions of the soldiers was disturbing and unacceptable to everyone.

Question:

Can you talk more about what you saw inside the museum after the ENDF left?

Yemane:

There was leftover food, alcohol bottles, military clothes, and materials from the museum’s collection scattered around. I also saw burned pictures, books, and destroyed heritage items, along with civilian clothing and destroyed vehicles. There were materials used for torture, including electric cables, chains, and chairs used for detention and torture. I personally found torture devices like electric cables for shocks, chains, and different civilian photographs, residential IDs and bank account books, as well as military documents left behind.

Question:

Where were those things found? Were they in the main hallway, or were they in some of the smaller rooms? What spaces do you think were used for torture?

Yemane:

The torture devices were found in various places within the compound, including inside the library and the hall. The hall itself was used for multiple purposes, such as cooking, sleeping, and even as a toilet and dump site for their leftovers. The chains and other torture materials were scattered throughout the compound, but the majority were located on the ground inside the museum hall. There were three main areas where torture occurred: the first was in the center of the museum hall on the circular ground, the second was in the basement, and the third was inside the library.

Question:

You saw wires that were used for electric shock. What other evidence did you find that violence took place in the museum?

Yemane:

We collected the torture materials that we found with the museum. Later [after July 12, 2021, when some 10,000 ENDF soldiers captured by the TDF during the eight month fighting were held in Mekelle as prisoners of war] and we had the chance to speak directly with the coordinators of the center to find soldiers who had occupied the museum and to collect detail information .

We found the ENDF military leftover documents that shows which division was stationed there. According the documents we found, it was divisions 24 and 32. From the testimonies of the people held prisoners there, we learned that they were using the museum as a temporary detention center. We also met a woman who had been raped inside and shared her testimony with us and with the Tigrayan Genocide Inquiry Commission experts. She told us she witnessed four other women being raped as well. She mentioned a priest who was tortured and a former Tigrayan commander who had been detained in the museum before being transferred to a different area, South Ethiopia Arba Minch city, after two weeks. She also described the presence of other civilian prisoners who were dehumanized by the soldiers. She also witnessed a woman being forced to use the body of a martyr as firewood to prepare food as a means of torture.

Question:

Were you able to get a sense of how many people were held there as prisoners and tortured?

Yemane:

I don’t have an exact number, the Tigrayan Genocide Inquiry Commision is studying this area, so maybe they can have the number, but I don’t have exact number. As far as we know, it wasn’t a permanent detention center, but was used as a temporary holding place where prisoners were either transferred to a permanent detention center or to another temporary one. The survivor of sexual violence who shared her story with us stated that she was assaulted by the ENDF inside the museum. She also saw a Tigrayan man who had been a colonel in the ENDF before the war. He was detained in the museum for two weeks before being transferred to Arba Minch (Southern Ethiopia) prison.

Question:

Do you know if the ENDF was using the museum as a local prison, holding people from the nearby area? Do you know anything more about the victims?

Yemane:

The soldiers were arresting anyone who appeared to be a young man or woman in good physical shape, accusing them of being TDF fighters. This happened in various areas, not only in Mekelle, but also in other parts. They would bring these civilians to the museum and detain them. Only God knows what they did to them, but from the testimonies we have received, some were detained, tortured, and eventually released, or transferred to other detention centers. They also transported women and girls from different areas in military vehicles, raped them, kept them for several days, and then released them. They also used the museum as a collection site for various items gathered from Tigrayan farmers, including cultural clothing, cultural jewelry, and other important materials, which were looted, divided among themselves, and sent to their families’ homes.

Question:

Did you hear about any that any people were killed in the torture that took place at the museum?

Yemane:

I heard of several cases indicating that rape occurred in the area, and we found many civilian women’s clothes and shoes. However, we did not find any burials or dead bodies. It’s difficult to find detailed information.

We also found dehumanizing and aggressive words written throughout almost the entire building, targeting the people of Tigray and their leaders. One day, a doctor visited the museum with us and confirmed that the insults written on the walls were done with blood

Question:

You mentioned that they used parts of the museum as a bathroom, as a toilet, basically.

Yemane:

Inside the museum and around the compound, there was evidence of frequent urination, as the area was being used as a bathroom, and the smell was unbearable. We cleaned thoroughly, but the odor wouldn’t go away. They even cooked inside the hall, causing the floor tiles to turn black and leads to further deterioration of the building as a result.

Question

What are the museum plans moving forward? Are you going to try to preserve this history, as part of the history that the museum documents?

Yemane:

We are documenting all the activities that happened during the eight months, and are restoring the museum exhibitions. When that is finished, we will include, and we are planning to dedicate a space inside the museum that can clearly shows what happened here during the recent occupation. It will be part of the museum; it is part of our history and we will commemorate

We will build it again as a community. That is the only option we have.

Question

You said all the photographs were burned and many of the artifacts were destroyed — do you have enough material to rebuild the museum, the collection?

Yemane:

We have some electronic copies of materials, those materials will help us for its restoration. As I mentioned before, and it’s difficult because the museum was originally established with the support of people both within and outside the country. Currently, it’s not a government priority since it has other unsolved issues resulted from the war, but I’m confident we will rebuild it again at some point, with the participation of various experts and the community as whole, the materials will be collected. We will gather items from different sources, and the history will remain preserved and promoted for the purpose of education and research. The big constraints are financial.

Question

You and your colleagues — you work at a place that was designed to commemorate violence, and then it became a site of violence. How has this impacted you and your colleagues?

Yemane:

The museum was established to honor those who sacrificed their lives for justice and freedom. Seeing it damaged was deeply painful and hurts, emotionally, psychologically, yeah, and morally. Especially during the early stages of discovering the destruction. Now we are getting to use it and try to find a solution, but still sometimes it’s difficult to accept what happened to the historical and cultural site.

We also observe a range of emotions from the visitors; many shared their feelings with us, some crying intensely and others expressing anger. While some were devastated, as if they had lost their own child, others encouraged us, saying, we will restore it to its former state and show our resilience through hard work, not through tears. Before the war it was a very important place for children, student, researchers and visitors to come here and to see their history, but now it’s painful for everyone.

Question:

How has the local community responded to the museum? Has it changed at all, the relationship between the museum and the community?

Yemane:

Yes, as I mentioned before, the community members who visited became very emotional, and some of the younger ones, after seeing the destruction, immediately joined the TDF. Some people are asking us to rebuild the museum quickly and remove all traces of the destruction because they don’t want to feel weak or be seen as a people who couldn’t protect their history. This place was a significant and respected area. It served as an important reminder of our memories, resilience, and values. Now everything is gone and people are saddened and feel bad.

Question:

Is it open to the public now?

Yemane:

Yes, it’s open now and people come to see, but there is nothing to show except the destruction. But people come to the compound and take pictures by the memorial and share their concern and how they can help to restore the museum to its original state.

Question:

They didn’t destroy any of the structures, right? The memorial is still there, and the statues and the building is intact. They easily could have. They bombed Mekelle. Why do you think they left the structures, the visible, the really visible structures unharmed?

Yemane:

When I say the building is damaged, I mean it’s severely affected. The electrical system, security apparatus, lighting, and water systems are already destroyed. If they had more time, they could have completely destroyed everything. Even the memorial landmark is partially damaged. I also heard from people that there was a plan to bomb the memorials, but the commander ordered against it, saying it might increase public outrage and attract international attention. That’s why it wasn’t bombed.

Question:

We want to thank you for your time.

Yemane:

Thank you for asking me.