This is the second blog in my ‘World War X’ series. It looks at the role that World War Two plays in our thinking—and stops us clearly reflecting on world wars.

America’s superheroes went to war with the Nazis well before its government. Superman declared war on Hitler in February 1940. He smashed through German lines, swatted away fighter planes, and swooped down into the Führer’s lair. Seizing Hitler by the throat, he sped away to Moscow, grabbed Stalin too, delivering both dictators to court to stand trial for war crimes. Captain America wasn’t far behind. In his opening cover story in December 1940, he punched Hitler on the face.

America’s World War Two superhero storyline has endured more than historical fact. It begins with a sinister megalomaniac plotting to destroy freedom and annihilate the Jews, and, with an Axis of fellow evildoers, take over the world. Despite the warnings of farsighted statesmen such as Winston Churchill, America is a reluctant warrior, slow to join the fight, until forced to do so by a sneak attack. It then fights and defeats Nazis, its soldiers offering succor to the survivors of the concentration camps, with final victory delivered by a wonder weapon.

On war memorials across Britain, the words of the poet Rudyard Kipling are inscribed: ‘lest we forget.’ Kipling was the poet of empire, his contemporaneous ‘White Man’s Burden’ an exhortation to the United States to colonize The Philippines. Like so many words of remembrance, they also words of erasure.

Kipling was master of weaving the threads of imperial identity—the ‘lies that bind’. Yet he was consumed by the tragedy of the war. His son was among many whose remains lay in an unmarked grave. In ‘Epitaphs of the War’ Kipling wrote: ‘If any question why we died / tell them, because our fathers lied.’

Each nation has its version of the story engraved in national identity.

In the Soviet Union, it was the ‘Great Patriotic War’, and President Putin uses its myth to justify invading Ukraine to ‘de-Nazify’ it. For the Chinese it is the ‘War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression,’ or sometimes, the ‘Fourteen Years’ War’. The Japanese call it the ‘Greater East Asia War’ or the ‘Pacific War’. For many Asians, the war aim was liberation from empire—and the British, French, and Dutch were on the wrong side. Winston Churchill fought to preserve an empire and he is remembered differently in India, as responsible for wartime famine in which three million perished of hunger and disease.

America only commissioned its national World War Two monument in 1993, one month after the Holocaust Memorial Museum opened. Having brought the memory of Europe’s singular atrocity to the National Mall, the country needed to honor its soldiers too.

The Holocaust Museum places the visitor in the shoes of the GIs who liberated the camps. It conveys the message that America has the power, and the duty, to use its power to stop genocide.

When America fights, it doesn’t fight for territory, for vengeance, for power—it fights for justice and liberty, to free the peoples of the world from the shackles of oppression. Liberal interventionists concur with neocons that America, having written the international rulebook, shouldn’t be bound by it. Thus, NATO’s bombing Serbia of 1999 may have been illegal but it was justified, and terrorists are ‘unlawful enemy combatants’.

Benjamin Netanyahu is a master of the World War Two fable. Speaking to AIPAC in 2012, he decried those who criticized his call to bomb Iran.

I’ve heard these arguments before. In fact, I’ve read them before. In my desk, I have copies of an exchange of letters between the World Jewish Congress and the US War Department. The year was 1944. The World Jewish Congress implored the American government to bomb Auschwitz. The reply came five days later. I want to read it to you. ‘Such an operation could be executed only by diverting considerable air support essential to the success of our forces elsewhere…. and in any case would be of such doubtful efficacy that it would not warrant the use of our resources….’ And here’s the most remarkable sentence of all. And I quote: ‘Such an effort might provoke even more vindictive action by the Germans.’ Think about that – ‘even more vindictive action’ — than the Holocaust.

President Donald Trump finally played Captain America and struck Iran.

He went on to compare it with the bomb that ended World War Two, telling reporters, ‘That hit ended the war … I don’t want to use an example of Hiroshima, I don’t want to use an example of Nagasaki, but that was essentially the same thing.’

For the script to work, Trump must now get the accolades and peace must return, so the superhero can move to his next challenge.

There are other fables too. Military men who like to call themselves ‘realists’ invoke ‘World War Three’ is as a warning: we must arm ourselves precisely so that we don’t have to fight it.

In 1978, General John Hackett published The Third World War. Set seven years into the the then-future, it described how a capable and aggressive Soviet Union attacked an under-armed and timid NATO: a refashioned World War Two, with the Kremlin playing the role of Hitler. It was, according to reviewers, a terrible read, but it did its job of animating conservative columnists to condemn western moral and material weakness and label détente or disarmament as ‘appeasement’. Three years ago, Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis published 2034: A novel of the next World War. It’s better written, but its message the same.

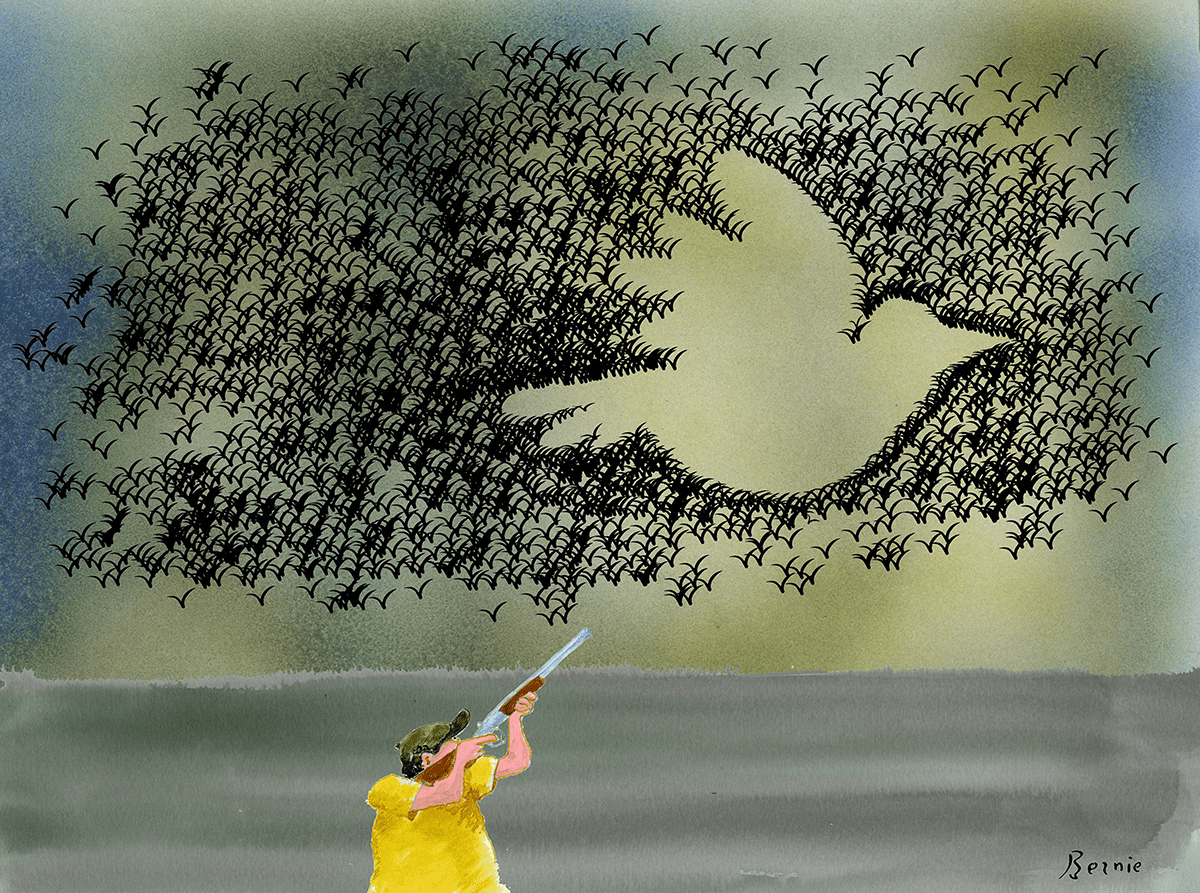

By these fables are the myths of the arms trade kept alive.

For the British military historian Lawrence Freedman, today’s wars fall into two strategic categories. One is ‘climacteric, capital-intensive, high-technology, militarily-decisive contest for political dominance between major powers. The other [includes] localized, labor-intensive, socially devastating, protracted struggle[s] which gain international significance only to the extent that the major powers chose to take an interest.’

This neatly summarizes how ‘World War Two’ and its imagined successor, ‘World War Three’ shape what we think. It’s the big powers that fight proper wars. The rest of the world doesn’t count unless America chooses to get involved.

It’s a logic summed up by a comment made by a British officer in command of a unit in the East African campaign of World War Two. Entering the Eritrean city of Asmara, he was greeted by a woman ululating in welcome, and said in irritation, ‘I didn’t do it for you, n***r.’ When the Free French forces assembled to march into liberated Paris in 1944, the American supreme commander ensured that the large contingent of African soldiers wasn’t visible in the parade: it was a whites-only triumph.

It’s the great power of the era who gets to decide what is a ‘world war’ and what is not. In World War Two, Britain passed that baton across the Atlantic. America’s wars are for the world and America gets to decide what is the next ‘world war’.

But we can’t make sense of a world war without also taking the viewpoint of the rest of the world.

The world’s memorial to World War Two is at the United Nations—in fact it is the United Nations, lest we forget.