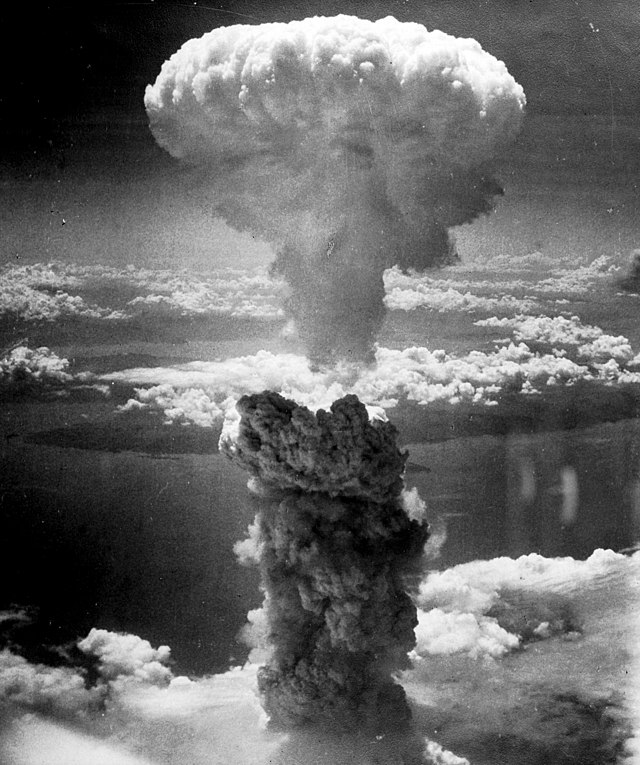

Hiroshima, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m. local time: clocks stopped and time passed.

At Hiroshima, humankind faced the possibility of a new war that would be waged from start to finish in a matter of hours and end civilization as we knew it. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set up the ‘doomsday clock’, a yearly statement of how many minutes, or seconds, the world is from midnight.

Violence twists time. This is not just a poetic observation.

During an act of violence, we often experience time in a slowed down way. And we may also act or react before we think—the action and the decision to act can’t be disentangled. Afterwards, the imprint of a moment of violence may be the survivor’s living present for a lifetime.

Or longer. Acts of violence can be intergenerational. The genetic damage done by the atomic bomb to the bodies of survivors, and their children, is the most horrifying example. The damage of malnutrition can also be transmitted from survivors to their children.

As acts of violence reverberate, cause and effect become blurred. Because a massacre is so terrible, we assume it must have been caused by hatred on a commensurate scale—deeply held by the group that perpetrated it. In fact, atrocities are often actions that feed on themselves—‘actrocities’ in which cruelty becomes an end in itself. Edward Weisband calls it the ‘macabresque.’ Violence makes enemies.

The analogy of the ‘root causes’ of war is accidently revealing. It’s intended to refer to something ancient, long-preceding the current moment. But that’s not how roots work. A plant grows from a seed and puts down roots at the same time as its shoots grow towards the light. Similarly, as a war expands and spreads, so too the roots of the conflict become deeper and wider, growing as they seek the nourishment it needs.

Violence can create disjunctures or singularities in historical time.

In Classical antiquity, heroic violence elevated the warrior to become the maker of a new world, destroying the old. This was the terrifying insight of Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who led the Manhattan Project at the ‘Trinity Test’ of the first atomic bomb. famously quoted, after witnessing the first atomic bomb test in 1945, and quoted the Bhagavad Gita, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’

In the Abrahamic traditions, the zealots’ logic of violence is human action can provoke G-d to intervene, to bring about cosmic change, or the End Times.

Some geologists use the radiation imprinted on rocks from the first nuclear weapon as the marker of the first day of the Anthropocene—the current era in which mass industrial production and consumption is changing the Earth’s systems. The Anthropocene has many elements. Among them is the Thanatocene—the mass organization of energy and material resources for total war, of which World War II was the most absolute case to date.

August 6, 1945, marked a vast human tragedy, a crime, and a warning.