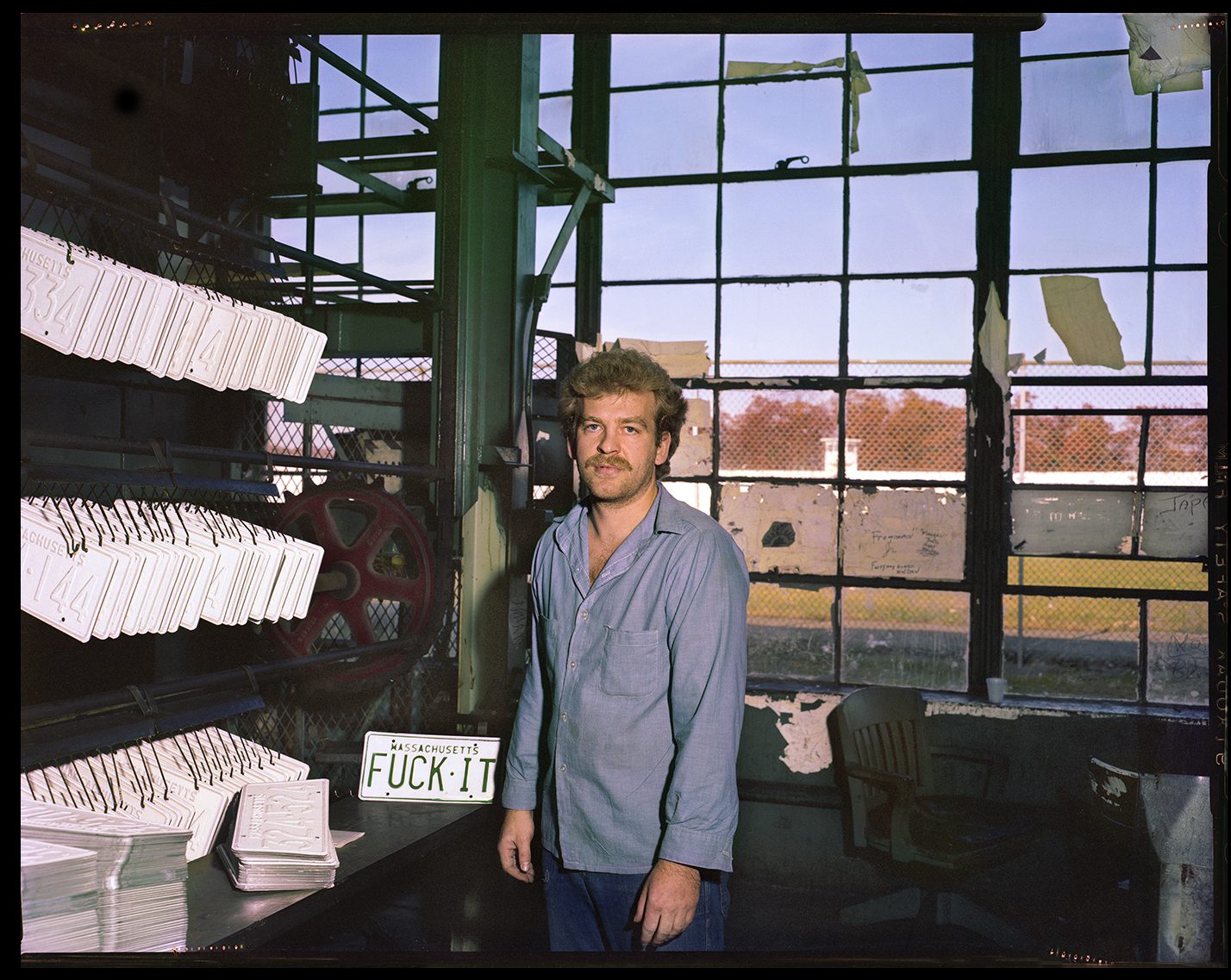

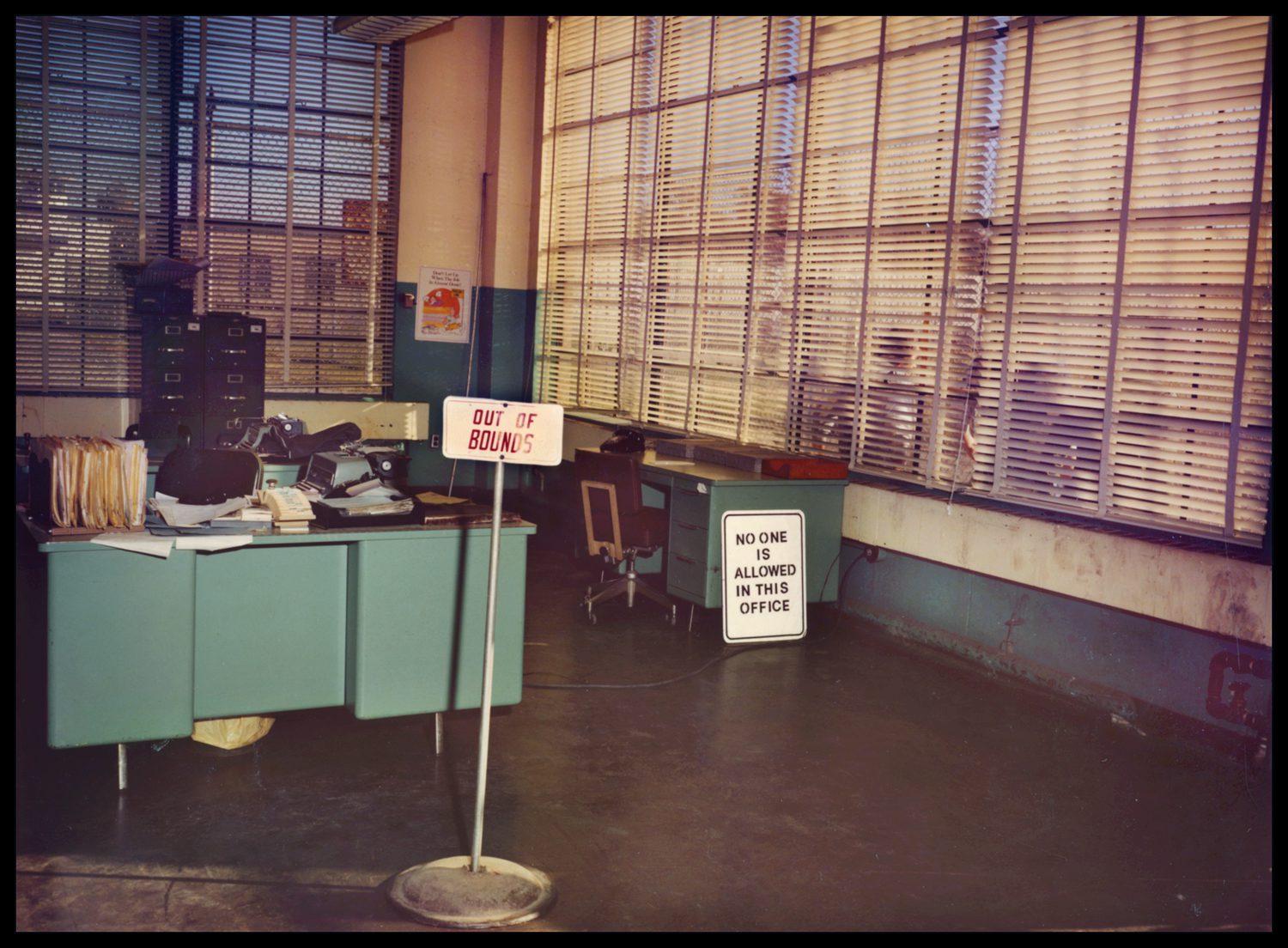

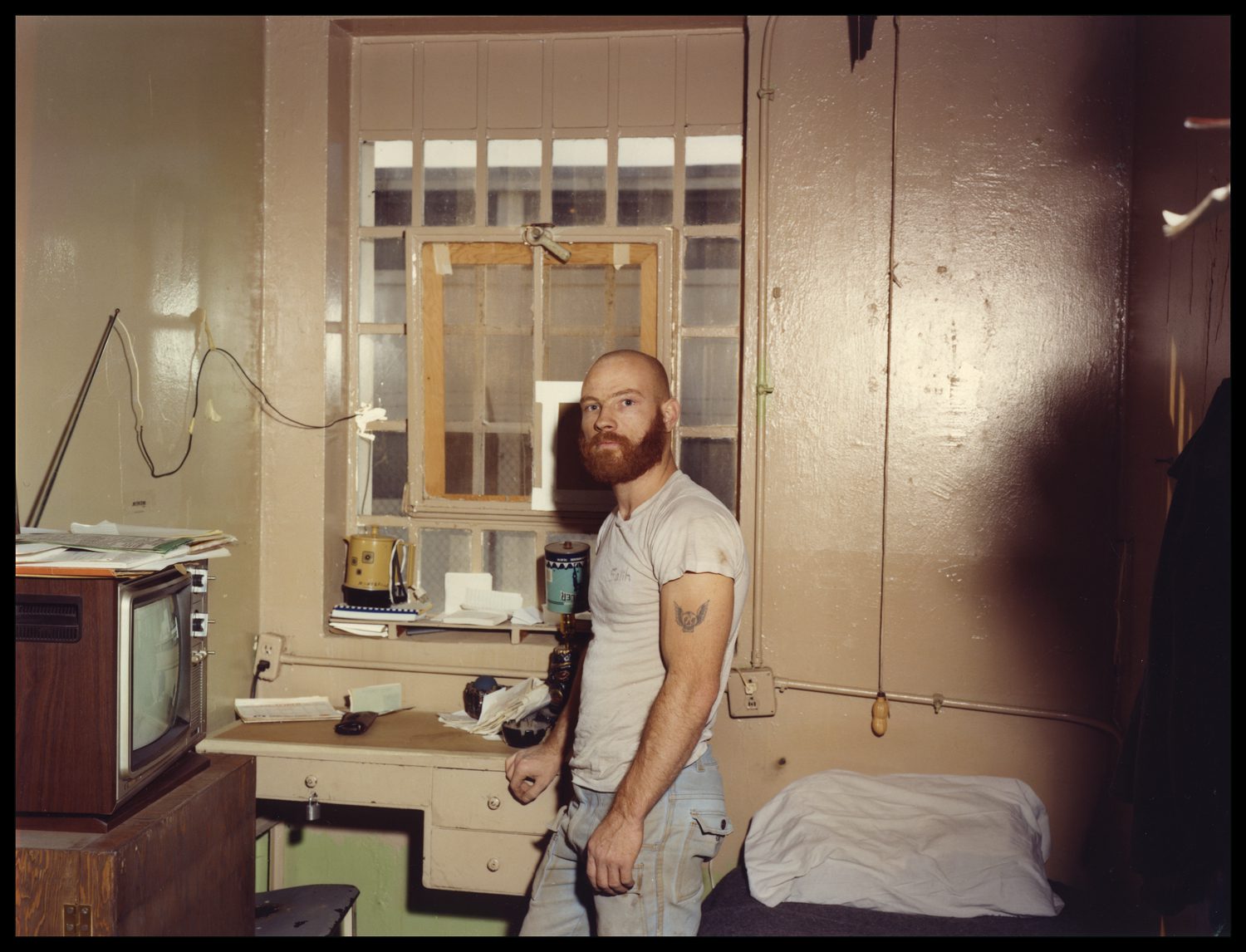

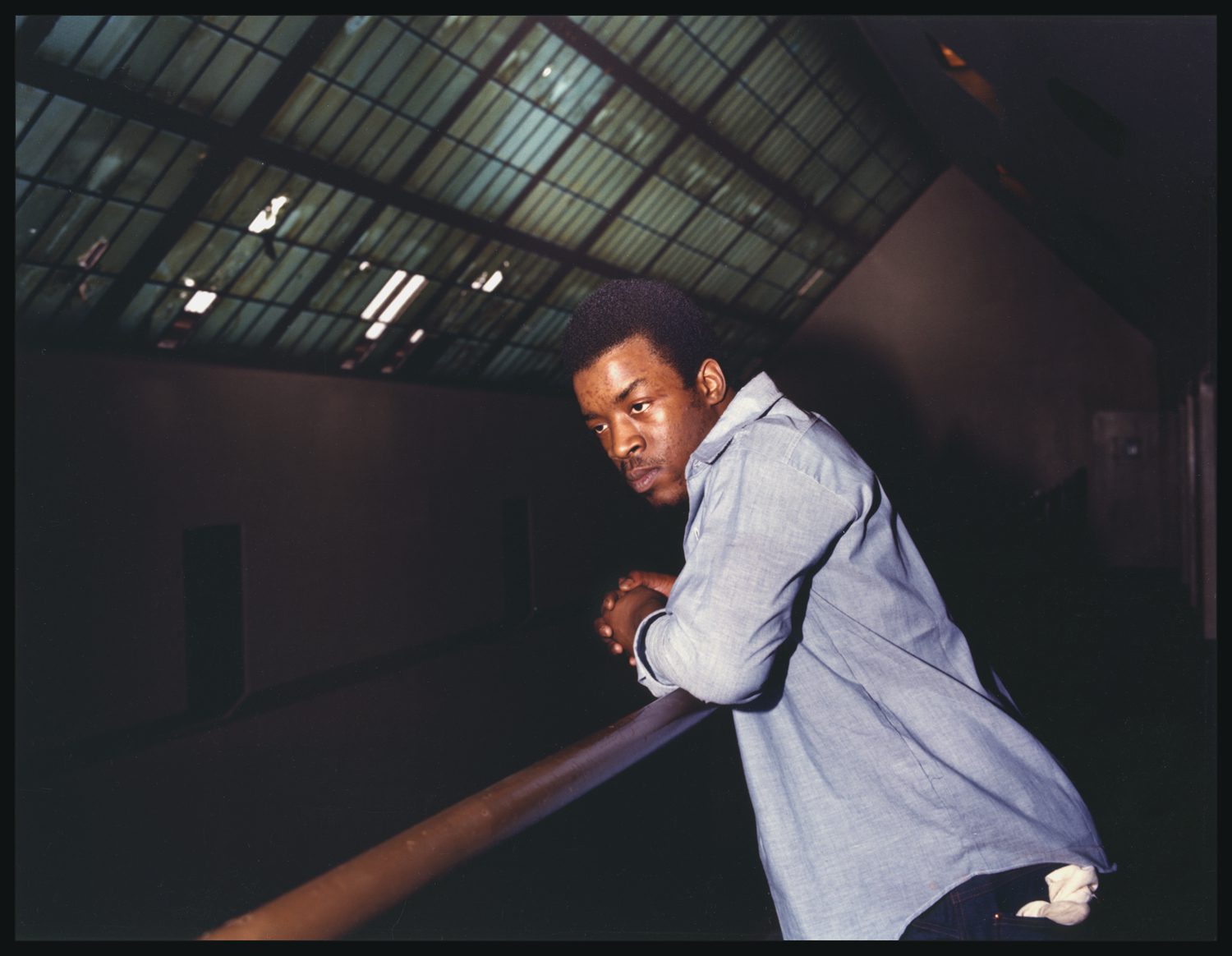

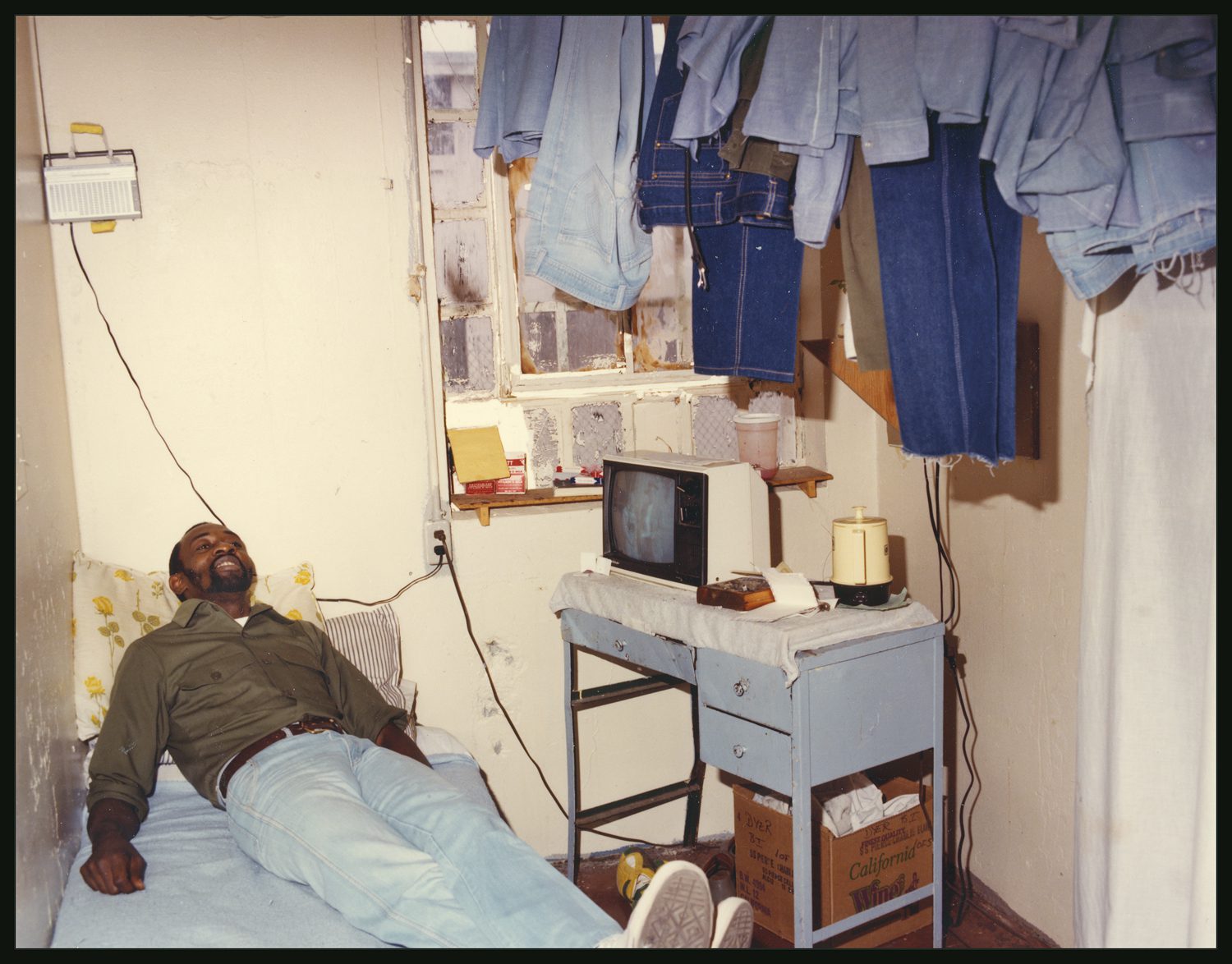

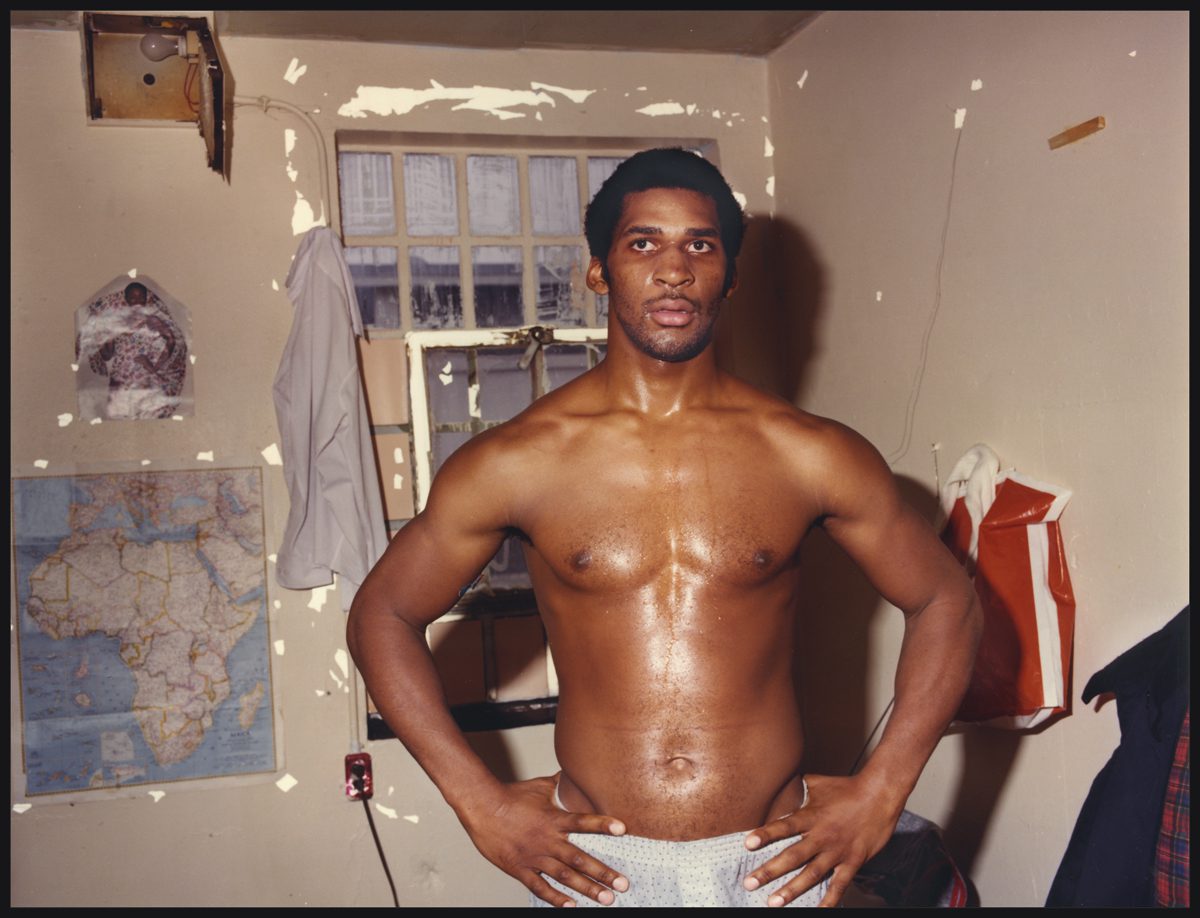

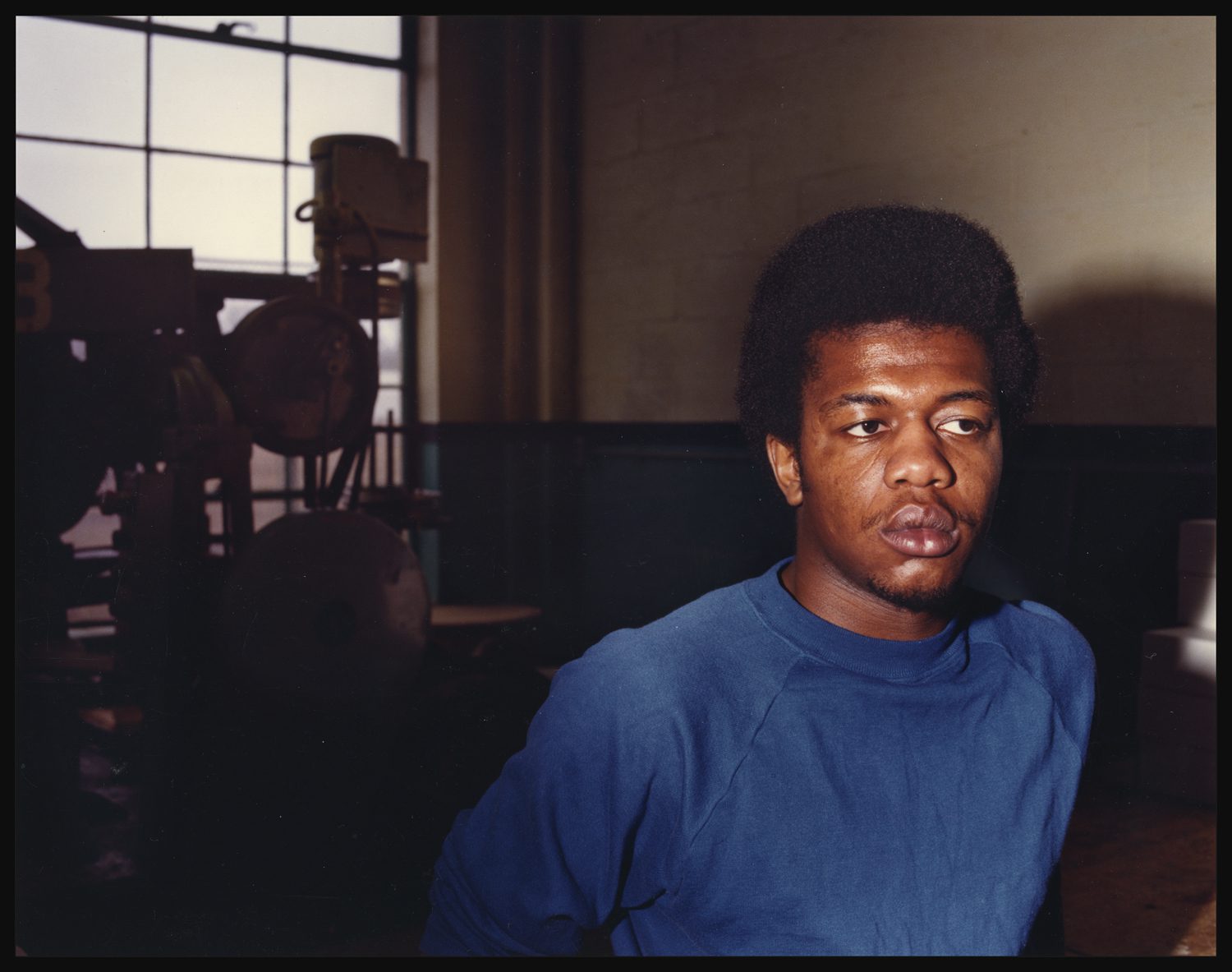

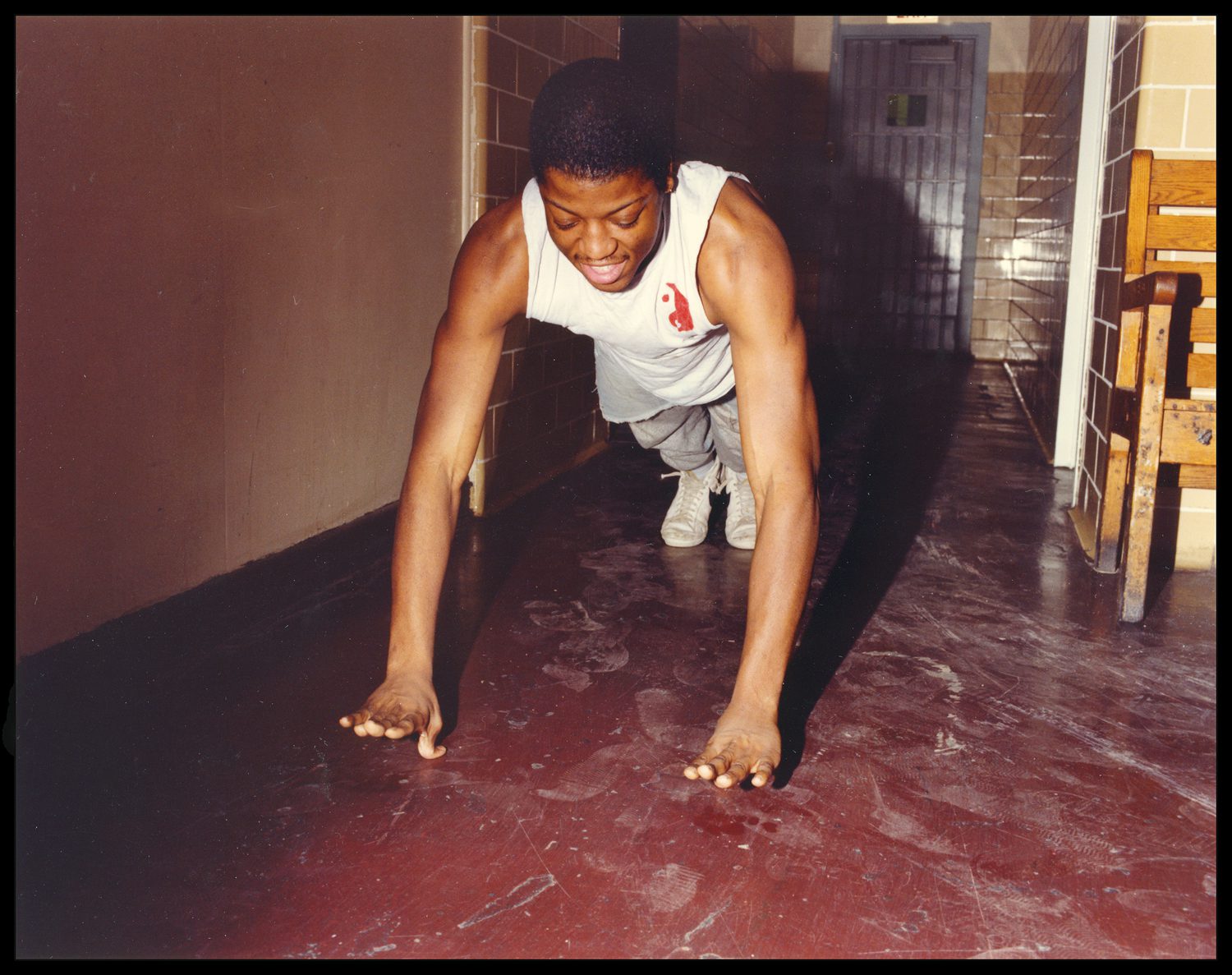

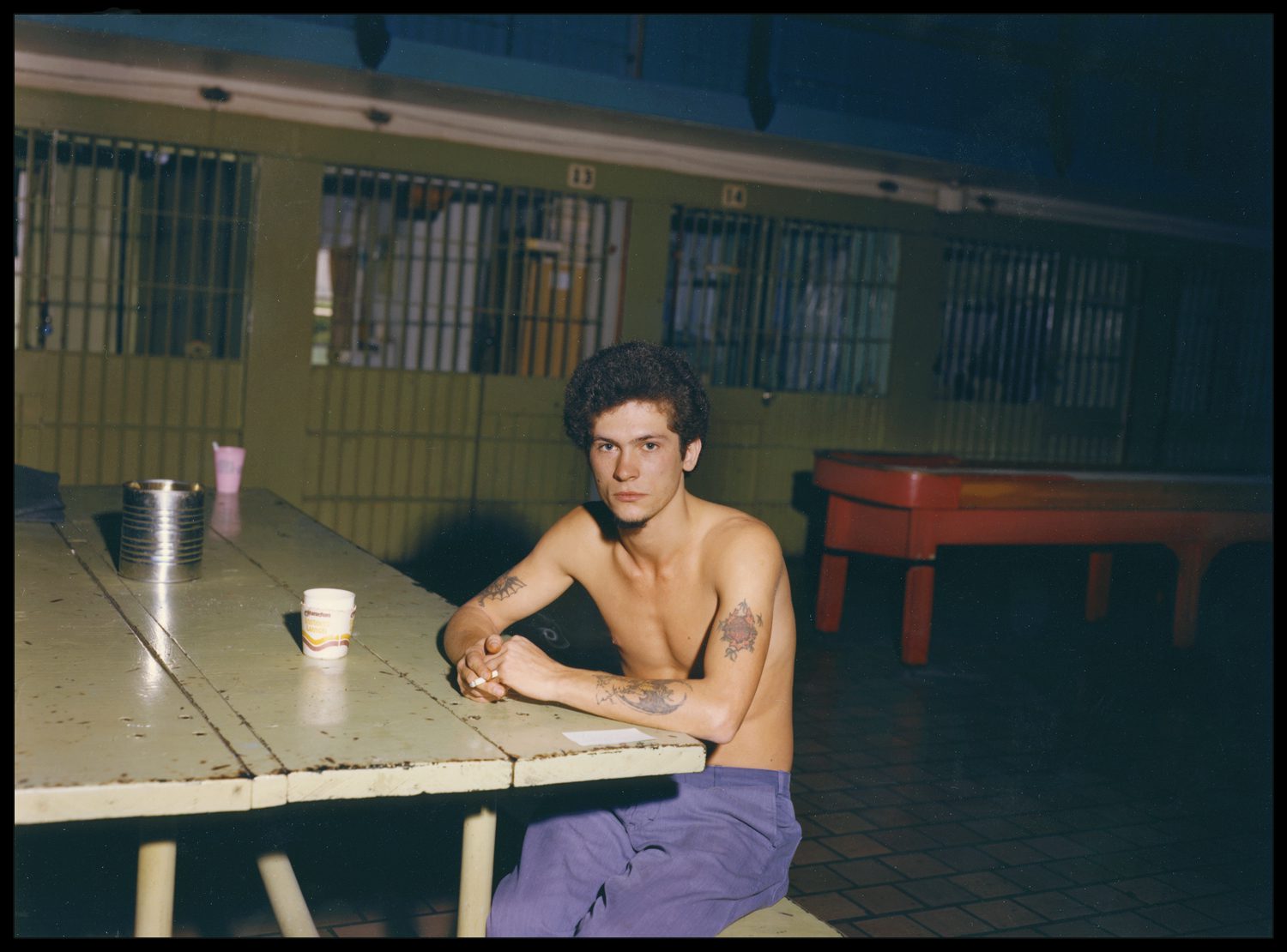

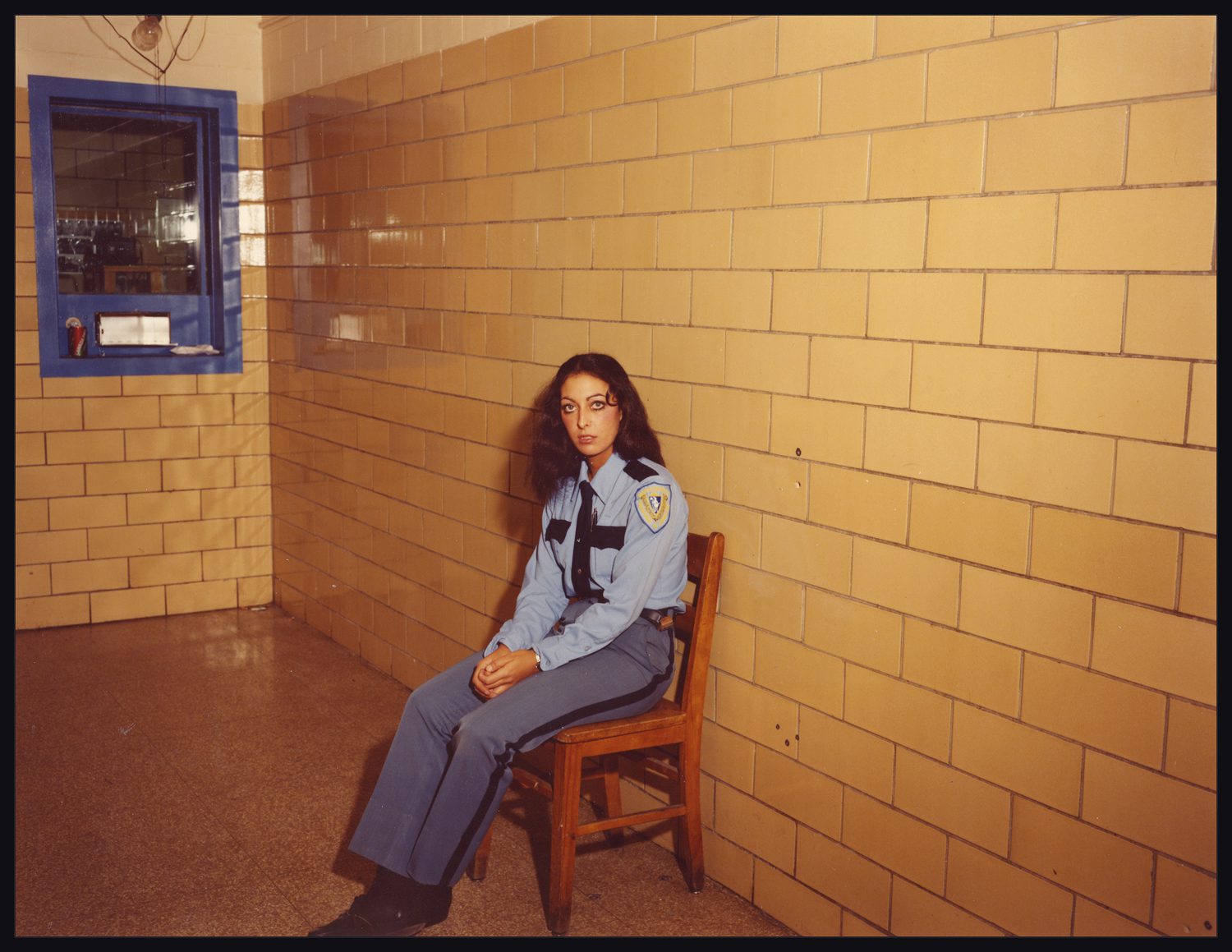

Note: Image above and gallery below were taken at MCI-Walpole (1981 – 1982) by Stephen Milanowski, who generously allowed us to publish them with this essay.

Around the world, societies struggle over what to do with abandoned structures where violence and injustices once took place. Prisons often loom large within these memory-struggles. In some locations, like the Robben Island (South Africa), Tuol Sleng (Cambodia), or the ESMA Museum and Site of Memory (Argentina), memorial activists transformed abandoned detention centers into sites for education and awareness. In the U.S., this practice is rare. Among the few examples are Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia which provides crumbling lessons against solitary isolation, and museums created from Japanese-American internment camps, like Manzanar. The issues at stake in addressing the violence of mass incarceration and brutal policing are also being addressed by the Chicago Torture Memorial and Justice Center in memorial form, including through reparations. But these examples are outliers.

A new opportunity to consider what to do with a decommissioned prison arose this summer in Massachusetts.

On June 21, 2023, Massachusetts Correction Institution (MCI)–Cedar Junction, formerly known MCI-Walpole – stopped housing incarcerated people. The state’s most notoriously violent prison has been shuttered with very little fanfare, let alone public discussion of what to do with the buildings and campus that will soon be completely abandoned.

In the weeks before it closed, the prison housed 525 men, the Department Disciplinary Unit (DDU), a Behavioral Management Unit (BMU) and the reception and diagnostic center (for men) for the state’s prison system. In 2023, the population at Walpole was disproportionately composed of minorities — 40% Black and 29% Hispanic, only 26% white – as it had been for years.

The most challenging part of determining what to do with structures is confronting the legacies of violence that enabled a structure to shelter violence for decades. This means returning to history.

Walpole was born out of reform. On January 18, 1955, four men escaped from Charlestown’s overcrowded prison, and Governor Christian Herter responded by establishing a commission to study the penal system, chaired by the President of Tufts University, Nils Wessel. The Wessel Commission urged the state to undertake reforms, including creating citizen reviews of conditions, councils of incarcerated people, and a standing board to review complaints, make recommendations, and evaluate programming. Most reforms went by the wayside – and a new prison was built instead.

MCI-Walpole opened in 1956, as a replacement for the Charlestown prison which then closed. The new prison housed men in the general prison population, plus two restricted housing units for special purposes (Bissonette, 22). Block 9 held people on death row and the electric chair. Block 10 was a punitive unit with infamous “blue rooms” where incarcerated people were housed without clothing or blanket. The rooms included only a “urine-stained mattress,” a drain, inadequate light and ventilation (Kauffman 30 -31). An officer described them as being like a:

“…ceramic tile shower stall . That’s what the floor and the walls and the ceilings are . The drain is like a shower drain and that’s where they go to the bathroom . And it’s filled with water, and everything’s floating around in there . The mattress [is covered with maggots and cockroaches. Guy’ll be sleeping and you walk down there and they’ll be crawling all over him.” (Kaufman, 31).

Judicial review offered no respite. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decided in 1982 that confinement in “box car” cells was not “repugnant to contemporary standards of decency” and did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment (Libby v. Commissioner of Correction, 1982, p . 421 ; cited by Kaufman, 30).

Not many years passed before the replacement prison plumbed even greater depths than its predecessor in terms of unsanitary living and working conditions, and widespread brutality. Life inside garnered significant attention, especially during the 1970s and 1980s, when Walpole’s notoriety was amplified by three factors: a period when the guards went on strike and people inside ran the prison (1972); Stuart Grassian’s canonical study of the psychological impacts of solitary (1983), and Kelsey Kauffman’s publication of Prison Officers and Their World (1988) which drew on extensive interviews with guards to paint a picture of the prison in the 1970s as an excrement- and blood-strewn prison scarred by violence perpetrated by both incarcerated people and guards.

In the fall of 1972, incarcerated men at Walpole organized themselves into a union, the National Prisoners Reform Association (NPRA), born out of collaborations between the majority white men and Black men (who also organized as the Black African Nations Towards Unity, or BANTU). They began working together to uphold their human dignity, improve their living and working conditions, and advance their cultural rights and educational opportunities. One leader of the movement, Robert Dellelo, had a more ambitious vision: “I wanted to see Walpole closed” (Bisonnette, 85). The period is documented in intricate detail in Jamie Bisonnette’s When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: A True Story in the Movement for Prison Abolition (2008).[i]

In March 1973, Walpole’s officers went on strike and NPRA took over the prison, running it peacefully for two months. Before the strike, tensions had been building between guards’ union and a new Commissioner, John Boone, a Black corrections professional who was hired to reform conditions of confinement in the state. The officers’ strike ended when the Governor called in the state police to retake control of the prison, a process that included severe beatings of incarcerated union leaders. Rather than building on the short peaceful interim and engaging incarcerated people as partners in improving conditions at Walpole, what followed was serious crackdowns and continuations of the pre-existing violent and dehumanizing conditions at the prison.

Kaufman’s research with prison officers describes these conditions as violence that regularly turned sadistic: people “did not just die at Walpole. They were mutilated, castrated, blinded, burned, stabbed dozens of times or more. Then they died” (Kaufman, 118). Violence, he notes, in the eyes of both incarcerated people[ii] and the guards, was “natural, a way of life, even a game if played within certain rules” (Kaufman, 157-8). A minority of truly violent guards dominated the guard culture, controlling and determining the overall environment. Decent people either left or learned to submit to the violent minority (Kaufman, 209). He notes that the only prison officers prepared for the levels of constant vigilance and inured to violence were Vietnam veterans (214, 223). The prison was a war zone made possible by dehumanization:

“…officers went to prison and they spoke of maggots killing each other, of inmates bleeding and dying, not men. [from interview with a guard:] ‘What happens here to the inmates does not bother me now in the least. I have no compassion for the inmates as a group. … I used to pass out at the sight of blood. Now it doesn’t bother me. It’s inmate blood’” (Kaufman, 231).

By 1978, a third of people incarcerated at Walpole requested protective custody – solitary — rather than live within the general population where beatings, torture and murder were commonplace (Kaufman, 29). Kaufman documents the first time an officer recruit visited Block 10: “’I walked in. I said to myself, I haven’t even seen zoos where animals live like this. There was shit, garbage, everything, thrown all over the place. Human shit. And it stunk” (Kauffman, 30).

Guards were vulnerable as well. Kaufman cites Department of Correction study report the documented 85 assaults on Walpole staff between 1 July and 31 December 1976, and during a particularly volatile period in 1979, Walpole officers staged a walkout charging that over a three -month period “39 correction officers were stabbed, blinded, beaten severely and scalded ” by incarcerated people (Kaufman, 123). He also documents regular incidents in which guards would single out men for extreme beatings, held down by several guards while being kicked and punched by others.

These conditions provide the background to Grassian’s investigations on the impacts of solitary isolation, which occurred at some point between 1979 and 1983 (exact dates of the interviews are unspecified). Grassian’s research was part of a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation of 15 men at Walpole, all of whom were plaintiffs in a class action case against the prison alleging violations of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The men were held in Block 10, which is four tiers, each with 15 cells. A set of outer steel doors to each cell were generally open until August 20, 1979, when new protocols closed them firmly, blocking all natural light from entering the cells. Grassian and his research team found that men experienced hyperresponsivity to external stimuli, perceptual distortions, hallucinations and derealization experiences; affective disorders (anxiety); difficulty thinking concentrating and memory; disturbances of thought content (aggressive fantasies); paranoia; and problems with impulse control (Grassian, 1452-1453). For most, the symptoms rapidly diminished once they were released from solitary.

Grassian concluded: “The observations at Walpole…strongly suggest that the use of solitary confinement carries major psychiatric risks” (Grassian, 1454). The study is now iconic – even if later research has revealed varied factors that impact how someone will respond to solitary[iii]: pre-existing mental health issues, the amount of time inside, multiple periods within solitary, and how conditions in solitary compare with conditions among the general population of incarcerated people.

There is no reason to believe that conditions improved into the 1980s. In 1981, Brian Wilson was an aide to Massachusetts Senator Jack Backman, Chair of the Massachusetts Legislative Committee on Human Services. Hearing from families and loved ones’ of people inside Walpole, he began documenting conditions and compiled what he found into a report submitted to Amnesty International (AI). The report included appendices that “document a clear pattern and history of systematic torture at the Massachusetts ‘Correctional’ institution at Walpole. It will also detail the practice of shipping prisoners out to facilities within other states and the Federal government located hundreds, even thousands, of miles away, i.e., exiling those who it appears have created the most ‘political’ problems for prison officials.”

The report concentrated on abuses in Block 10. Wilson concludes his letter to AI by stating: “we do feel that we have enough evidence, just by its weight, to have revealed a factual, tragic pattern of torture and brutality at Walpole prison, topped off by the threat of exile.” Following his submission of the report, he started receiving a series of threatening phone calls, which he surmised were instigated by the officers’ union, and took a temporary leave of absence as a personal safety precaution.

Infamy has costs. In 1985, residents of the town of Walpole pushed the state to re-name the prison, so that their town would no longer be synonymous with prison itself. The prison was re-christened MCI-Cedar Junction, although many continued to refer to it as ‘Walpole’ regardless.

The prison made headlines through the 1990s in relation to yet more violence. As examples: February 6, 1993, The Worcester Telegram and Gazette[iv] reported that 75 incarcerated men were involved in fights in the yard for about an hour using homemade knives and socks stuffed with rocks as weapons. Guards called in a tactical unit and dogs to quiet the violence. On February 19, 1993, the Gay Community News[v] reported that a man sentenced for his role in a sex ring was identified by guards to other incarcerated men, who beat him. He was then placed in a “holding cage” where other men spat and urinated on him, one guard intervened, but later the man was returned to the cage for more abuse. From Sunday to Wednesday, in deep winter, he was placed without a blanket in a cold cell with a broken window and no light source. He was then transferred to Concord. On July 14, 1993, the DOC spokesperson is quoted as saying that several incarcerated people were sent to a nearby hospital following a riot in which no officers were hurt and no property was vandalized, and the administration did not know the cause.[vi] In 1998, a story ran in The Daily Record (Baltimore) describing how an incarcerated man found himself inside Walpole being guarded by a person he had shot years before. The officer used his authority over the incarcerated man in “a pattern of abuse of his position… that resulted in a series of assaults, uses of excessive force, verbal and physical harassment and filing of false disciplinary reports.”

In more recent years, conditions at Walpole/Cedar Junction were addressed primarily in terms of how the DOC managed the Department Disciplinary Unit (DDU). The 2018 Criminal Justice Reform Act (CJRA), which required for the first time that all people held in restrictive units – that is, locked into their cells for more than 22 hours a day — be provided three meals a day, regular access to showers, reading and writing materials, mental health examinations, and clinical treatment. In addition to implementing new procedural reviews, the DOC was now required to report on the number of people in the DDU, why they were there and how long they were placed in solitary, among other reporting requirements. People can still be placed in the DDU for up to 10 years.

Despite reforms, the DDU at Walpole/Cedar Junction came under fire when, in 2021, the DOC hired a consulting firm, Falcon, Inc., to assess its restrictive housing policies. Falcon found the 57% of people in the DDU had open mental health cases in 2019 (Falcon, 19) and noted that the DDU procedures are:

“…an important departure [from those established by the American Correctional Association and National Commission on Correctional Health Care], and one that allows for up to ten years of confinement in conditions that would otherwise be labeled as Restrictive Housing by most definitions (i.e., average of 22 or more hours per day confined to cell, longer than 15 days, without the order of a healthcare provider).” (Falcon, 9)

Interviews revealed that people in the DDU felt that “they were being warehoused and unfairly punished,“ and were treated like animals (Falcon, 25). Men described their limited time out of cell as largely consisting of being shackled to a chair and staring at a wall (Falcon, 25). Falcon wrote: “The innately punitive culture of the DDU minimizes the interests of rehabilitation or positive behavior change to address the underlying causes of the infraction that led to placement in the DDU” (Falcon, 30). The DDU was, in short, counterproductive and the consultants recommended dissolving the it entirely (Falcon, 4).

On June 29, 2021, the DOC announced it would eliminate all restrictive housing (defined as housing where people are in their cells for more than 22 hours/day) over the course of three years. One year earlier than initially planned, Walpole/MCI-Cedar Junction and the DDU closed.

By June 16, 2023, all the incarcerated men at Walpole/Cedar Junction were transferred to other prisons and the diagnostic center was moved to Souza Baranowski Correctional Center (SBCC), a maximum security prison. A skeletal staff remain at Walpole to maintain the prison facility, until they can be reassigned elsewhere.

I recently spoke briefly with three colleagues who spent years at Walpole/Cedar Junction in the late 1980s – 1990s. I asked how each felt about it closing. One, who had spent 10 years in solitary there, told me he had nothing to say. Another simply described the prison as “awful” and expressed gratitude that it was closed. The third man said that Walpole was a torture chamber. Closing it for him was a big deal, “not everybody made it out the same as they went in…yeah…I’m happy to see it go.”

What should the state do with the now-empty shell of this prison?

An answer to this question is informed by Kelsey, who issued a prescient insight in 1988. Rehabilitation was en vogue in the 1960s and 70s, by the 1980s it fell from favor and prison was pure punishment. Noting that rehabilitation would likely cycle back into favor, he warned us to remember that the only thing prisons consistently accomplish is to debilitate virtually everyone who spends time inside them, incarcerated people and staff alike. And the problems don’t remain inside the wall: “The presence of enclaves of brutality and deprivation, created and sustained by governments on behalf of citizens, literally demoralizes-that is, corrupts the morals of-the society as a whole.” (Kelsey, 268).

Transforming prisons or former sites of violence into museums can open opportunities for the public to learn about what happened and be warned about how easy it is for societies to accept dehumanizing brutality. I am not sure Massachusetts, or anywhere else in the US today, is ready to see mass incarceration in the terms of condemnable violence. If we are unwilling to confront unacceptable levels of state-sponsored violence, then the only other option is to tear the prison down.

Notes

[i] Bisonnette, Jamie with Ralph Hamm, Robert Dellelo, and Edward Rodman. 2008. When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: A True Story in the Movement for Prison Abolition (Cambridge: South End Press), pp. 18 – 21. See also a March 2023 conference at Harvard University’s Mahindra Humanities Center marking the 50th anniversary of these events.

[ii] Note, however, Kelsey’s research is based on interviews only with officers.

[iii] Labreque, Ryan M., Robert Morgan, Paul Gendreau, and Megan King, 2020. “Revisiting the Walpole Prison Solitary Conferment Study (WPSCS): A content analysis of the studies citing Grassian (1983)”, Psychology, Public Policy and Law 26:3, 378-391.

[iv] AP, “2 Prisoners stabbed in melee at Walpole,” Worcester Telegram and Gazette (February 6), A6.

[v] Hyde, Sue. 1993. “Davis Beaten at Walpole,” Gay Community News (February 19).

[vi] AP, 1993, “Riot is quelled at Walpole,” New York Times (July 14) A2.