Are the victims and survivors of genocide in Tigray condemned to suffer in silence, their voices unheard by the world? Are the authorities—in Tigray, in Addis Ababa, and internationally, closing the door to truth-telling, and trapping the Tigrayan people in silences, lies and further victimization?

The war in Tigray, Ethiopia, from November 2020 to November 2022 has exacted a human toll—from massacre, hunger, disease, and on the battlefield—that matches or even surpasses Gaza, Sudan, or Ukraine. In Gaza and Sudan, victims are crying out to be heard and reliable data are hard to find. In Tigray, the information is all available. But it’s being erased.

Human traumas of the war have been assiduously and sensitively documented by Tigrayans and those who work with them.

The compilation of testimonies by Birhan Gebrekirstos and Mulu Mesfin, Tearing the Body, Breaking the Spirit: Women and Girls’ Rape Stories from the Tigray War, provided compelling, visceral accounts of the utter cruelty inflicted on Tigrayan women and girls during the war. The stories they recount are from the eight months when the Ethiopian National Defense Force and the Eritrean Defense Force occupied Mekelle and the major towns of the region, inflicting a reign of terror. The words ‘rape’, ‘sexual violence’ and even ‘genocide’ fail to convey the meaning of the acts, that strip away the personhood of the victim.

The book was published in 2023 and the authors note that reports of sexual violence had not ceased. Nor have they ceased today.

And the survivors of sexual violence are still living their traumas every day, stripped of a future, stripped of womanhood, denied family and community. Hunger and destitution are for many the lesser of their torments. Some have found it impossible to continue living.

Other Tigrayans have also recorded atrocities and published books. There is Axum Cried, a book in Tigrigna detailing the massacre of Axum that in a broad daylight took the lives of over a thousand citizens. In War on Tigray, by Daniel Berhane details the genesis of the war and its early effects. In Primed for Death, Goitom Mekonen Gebrewahid gives a compelling personal account of the genocide. All these books were published in the year after the end of hostilities, in the hope that they were cracking open to door of documentation. Last year Jan Nyssen published A Chronicle of the Tigray Tragedy (2020-2024) that compiles his enormously informative digests during this period and a wealth of other sources. The authors all expected that the Tigrayan authorities would continue with the first, essential step of justice—ensuring that the victims are heard.

The French Centre for Ethiopian Studies has published a new compendium, Mekelle Stories: Life in Time of War. This differs in that its focus isn’t on the survivors of some of the most appalling crimes, but on a range of people who lived through the war, siege and hunger. Their personal testimonies cover the outbreak of the war, the entry of the federal forces into Mekelle and the months of occupation, life after the Tigrayan Defense Force recaptured the city but it was under siege, with people suffering extreme hunger, the final round of the war and the peace agreement. This offers a different perspective, perhaps less shocking but in their own way no less disturbing. These are stories of struggle to maintain family, to find money, to put food on the table, to care for sick relatives. They tell of intermittent terror with artillery bombardment or the cruel arbitrariness of soldiers manning checkpoints, and of the gnawing worry for the fate of those fighting at the front line, and the sadness of seeing young veterans of the war who have lost limbs, eyes, or mind. Reading these stories is a vivid and sad reminder of the traumas and losses to which ordinary people have been subjected, their dreams shattered, their lives turned upside down.

This important book comes as the door of recognizing the victims and survivors is being shut.

The International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia was shamefully closed down at the behest of the government of Ethiopia two years ago, on the entirely false promise that it would conduct its own investigations. The Commission did issue a report, which documented a range of violations, and also issued a sharp warning of ‘acute risk of further atrocity crimes.’ But UN reporting has since then fallen silent.

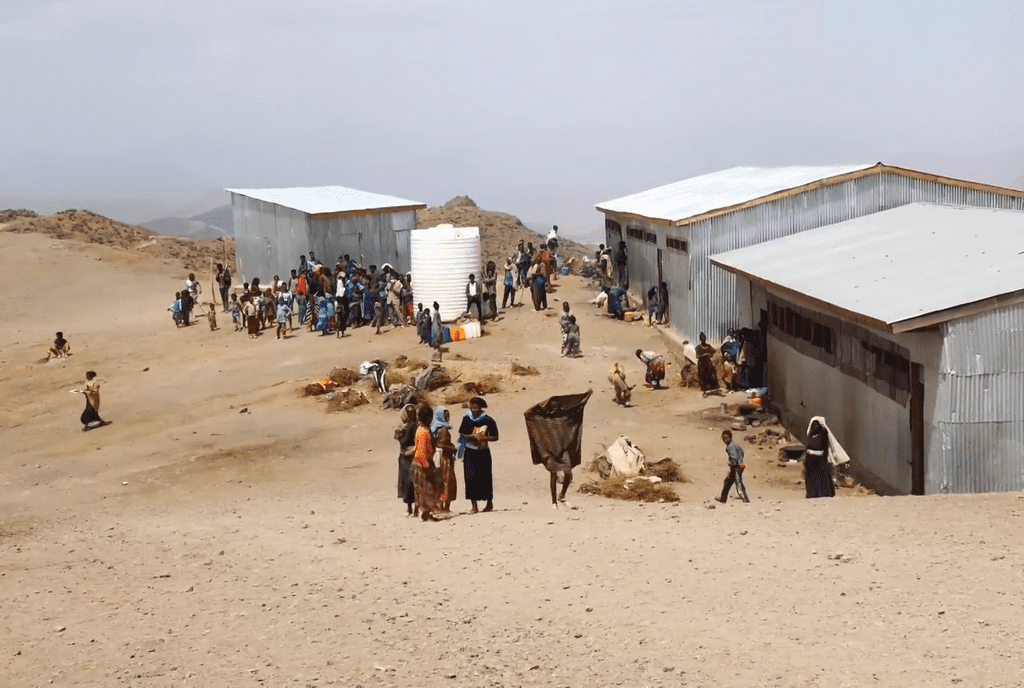

The UN Integrated food security Phase Classification issued its last report on Ethiopia, warning of a high risk of famine in Tigray, in July 2021. Its activities in Ethiopia were then closed down. It is negotiating re-entry, but it has not yet issued any new analyses, while the food emergencies in several parts of the country, notably Tigray, have worsened.

The Federal Government in Addis Ababa has every reason for wanting to close the book on Tigray, forget about its victims, and move on. Foreign donors, bewildered by the turbulence of Ethiopia and its neighbors, overwhelmed with other urgent crises, and ashamed of their indifference at the time of the slaughter, have many reasons to connive in this forgetting.

Eleven months after the peace agreement, Tigrayans came together for three days of collective mourning, honoring the dead of the war. Representatives from the Tigray Defense Forces visited the homes of every single one of their fallen soldiers to confirm the loss to the family and share their grief. It was a powerful indication that the genocidal onslaught had not broken the spirit of the people.

The Tigray Genocide Commission enlisted thousands of volunteers for the task of comprehensively documenting crimes perpetrated. Some of the information concerning economic losses was provided, in summary, to the World Bank. So we know that the data exists. But the Interim Administration is rebuffing any attempts to see that data.

This is vital and sensitive information. In the wrong hands, the data could be used to reproduce harm and deepen insecurity, particularly for survivors and others who came forward in hope of justice.

Do the politicians in power in Tigray want to suppress it because they don’t want to upset their allies in Addis Ababa and would-be allies in Asmara? Are they afraid because some of their own crimes will come to light? Are they planning to hand over these detailed files to the perpetrators so they can win political favor? Or are they so habitually secretive that they simply want to hold onto this precious information, willingly entrusted to them by the Tigrayan people, because they feel they own it?

Whatever the reason, locking away the files of the Tigray Genocide Commission is a shameless betrayal of the Tigrayan people. These records were entrusted in good faith by survivors and witnesses—many of whom risked stigma, retraumatization, or even retaliation to speak the truth. To suppress this archive, or use the data behind a cloak of secrecy, degrades the noble purpose for which it was collected.

The victims of Tigray’s genocide are dying twice.