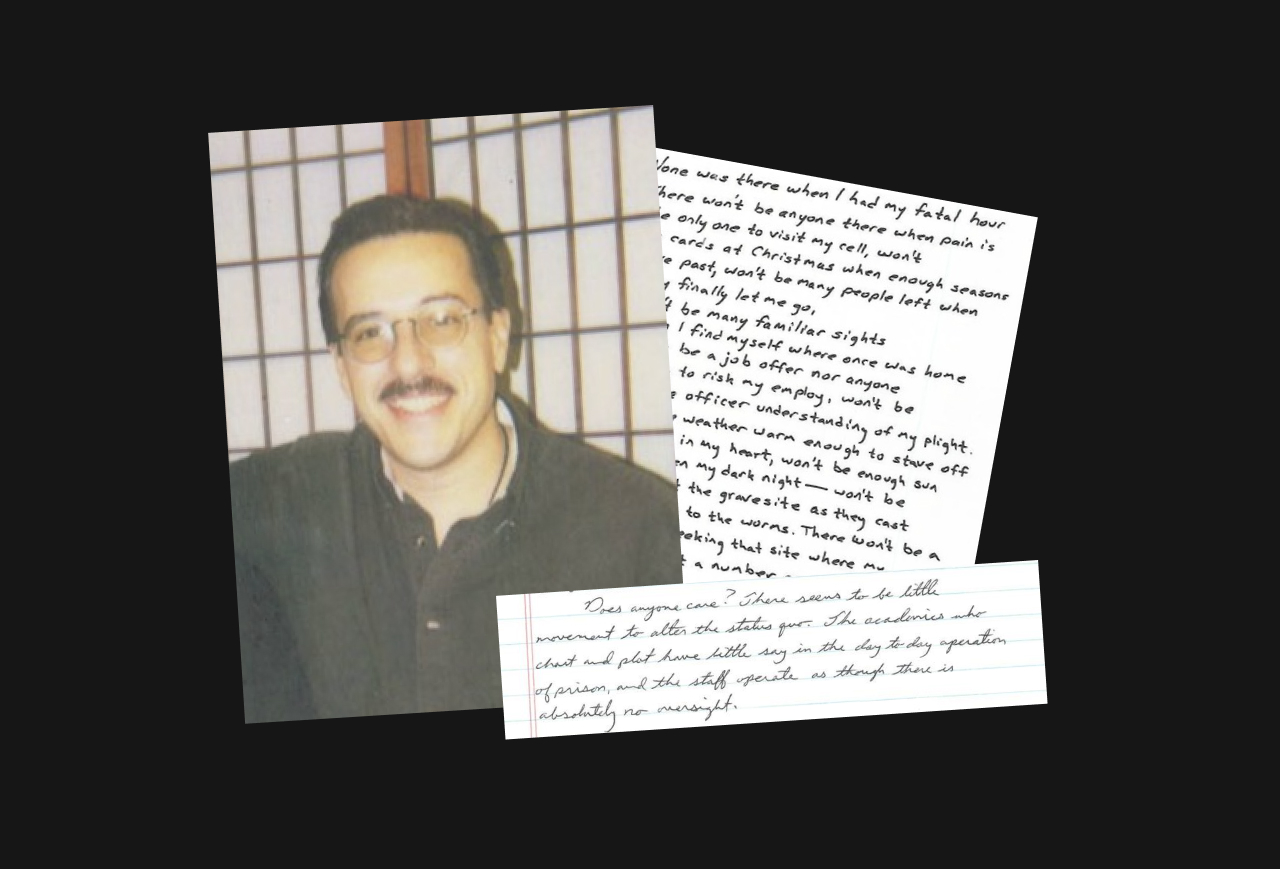

On November 17, 2023, Jorge L. Zerquera reportedly committed suicide while being held inside a Behavioral Adjustment Unit (BAU), at Massachusetts’ medium security prison, MCI-Norfolk. The BAU houses, according to the Massachusetts Department of Correction (DOC), “individuals removed from general population due to unacceptable risk to facility safety and operations” (3). As covered by GBH’s Margot Amouyal, Zerquera’s death shocked people inside Norfolk. Transferred from a Florida prison, he had only 12 – 14 months left on a sentence that had been reduced from life.

Following Zerquera’s death, William Duclos, also incarcerated at Norfolk, reached out to Claire Masinton of Mental Health Legal Advisory, in a letter subsequently published online. Duclos advocated for an investigation into Zerquera’s demise. He described Zerquera as a leader within the Latino community inside, an active member of the Native American Circle, someone who was always ready to help others, and who was known as having a calming effect on the overall community inside Norfolk. Additionally, for over 37 years, Zerquera was a part of Project Youth, an anti-violence program led by incarcerated people.

Duclos’ letter states that on November 15, Zerquera suffered a stroke and was prescribed vital “keep on person” medication – which authorized him to have the medicine in his cell. The next day, the medication was taken from his cell during a search. When he discovered it was missing, Zerquera requested access to it. The officer in charge, DePina, the letter asserts, refused the request. Zerquera entered the yard and began yelling that he needed his medication. Zerquera said that he felt like he was having a stroke. As a result of advocating for his health, he was placed in the BAU.

According to Duclos, within 7 to 8 hours, the DOC claimed that Zerquera had been “found hanging and passed away.” According to DOC Policy, “Upon an inmate’s placement into a BAU, healthcare staff shall be notified immediately in order for a heath/mental health screening review to be conducted” (8). The policy also states that “BAU/SAU inmates are personally observed by a Correction Officer at least twice per hour” and “security rounds shall be conducted at least every thirty minutes” (9). Given this, his death raises several questions about how the DOC implemented their own policies: Did a medical screening taken place? If so, what was documented in the Inmate Management Systems? Was Zerquera having a stroke? Which officers were responsible for observing Zerquera in the BAU and will they be held responsible?

Duclos states in his letter, “Suicide seems off and staff feel the same way.” He also noted that “there are several grievances and NIC Concerns forms being filled on this incident and officer (DePina).” I have submitted a request under the Massachusetts Public Records Law (Law), Chapter 66, Section 10 of the Massachusetts General Laws to the DOC to find out more information about Zerquera’s sudden death and the grievances that Duclos mentions in his letter. But will the state exercise its responsibility over this incident? Without an independent investigation, it is not possible to know what happened inside the BAU. Only an investigation that is conducted by someone who is fully independent of the DOC would be credible.

It is conceivable that this was a suicide. Severe mental health harm is consistent with what we know about the impacts of solitary isolation. The practice has been reformed in Massachusetts recently in the 2018 Criminal Justice Reform Act (CJRA) and in subsequent DOC policy changes. But the problem with reforming solitary isolation is that it forces advocates to enter the game of counting how many minutes of torture are acceptable. Thirty minutes separates the DOC’s BAU from its now abandoned Restrictive Housing Units (RHU) and Department Disciplinary Unit (DDU). Instead of being locked into a cell for 22 hours a day or more, as occurred in the RHU and DDU, people in the BAU are locked up for 21.5 hours a day.

There are no studies addressing what constitutes a “safe dose range” for solitary. This is because, as scholars, Brie Williams and Cyrus Ahalt argue, it would not be possible for researchers to create an experiment testing this question. Given what we already know about the harmful impacts, no research review board would approve such an experiment. Using a common public health measure of balancing harm and benefit, Williams and Ahalt note: “In the broader medical and public health research contexts, any treatment or intervention with the known risks and lack of demonstrable benefits associated with solitary confinement would be immediately removed from the market and all future research on it discontinued” (165 – 166). In short, in the U.S., it is only allowable to experiment with this form of torture on incarcerated people.

What we do know is that the DOC doesn’t seem to be obeying its own policies or the spirit of the CJRA. Recently, nine incarcerated individuals participated in a hunger strike in protest of the inhuman conditions at SAU at Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center (as reported by WBUR’s Deborah Becker), a maximum security prison in Shirley, MA. In response, twenty legal and advocacy organizations, including Prison Legal Services (PLS), sent a letter to the Attorney General’s Office to investigate DOC practices regarding these units. Bonnie Tenneriello, a Senior Staff Attorney at PLS, states “The claims in the strikers’ letter mirror harsh conditions that have been reported to our organization for years.”

Zerquera’s experience in solitary mirrors these claims. In a 2013 letter published by Between the Bars, a weblog platform for people in prison, he described the impact of solitary.

“[…] There are far too many instances, for me to catalog here, which reinforced the sense of desolation during my years in segregation. The practice is barbaric and inhumane. As such, those charged with the responsibility of confining men/women, objectify the people under their power.

How many times must you see the sun rising in the east before you realize that there is a pattern? How many generations of recorded observation, without any real variation, do you require before you settle upon an eastern sunrise as fact? Allow me to set before you a few facts:

1) Man is a social creature.

2) Isolation, for prolonged periods of time, can cause psychological harm.

3) People who assume the social role of prison guard are often corrupted by their power over their helpless charges.

4) Fact 3 exacerbates fact 2. I have lived amidst the people who make up the statistics of the studies which prove those facts. They are not data points to me, they are my fellow prisoners, and I am one of them. I listened to Thomas Knight speak of himself in the third person, after ten brutal years in the “hole” at Florida State Prison in Starke (to name one of the hundreds of men whose souls and minds I’ve seen crushed by isolation).In the hole there is no other voice than your own, so you could spend years finding fault in others and reinforcing an egocentric view of your suffering. There is no one there to counter or refute, so one can slowly spin into a new reality, one of his own design. This is not rehabilitative!

Does anyone care? There seems to be little movement to alter the status quo. The academics who chart and plot have little say in the day to day operation of prison, and the staff operate as though there is absolutely no oversight.” […]

— Jorge L. Zerquera, “Solitary Panel”, Between the Bars, March 10,2013.

The harm associated with solitary and solitary-like units is clear. Yet, the DOC finds ways to skirt or blatantly violate the CJRA.

Zerquera should not only be defined by his experiences in solitary. Over the course of his incarceration, he earned a degree from Boston University, graduating in 2012. He also assisted others inside prison to earn their degrees, hosting study groups and spending hours in the prison library. Recalling a favorite professor’s comments, he described what education meant to him: “Dr. Blackwill once told me that higher education does not only grow one’s mind, but it also grows their heart. It is good to have a part of her in my heart.”

A poem he wrote in 2011, “AND tomorrow,” captures the chasm that prison interjects between people inside and the world outside. Below is an image of the original handwritten text, as published by Between the Bars.

Towards the end of Duclos’ letter, he states, “Jorge will be missed.” It is clear that that Zerquera’s life inside, the contributions he made to the community at Norfolk, his writing and his leadership, will prevent his memory from being nothing more than “number on a marker.” His life was meaningful, despite the harm he experienced at the hands of the DOC.

His death should also be a wake-up call to those can do more. At least two directives follow from this awful death. Do not reform torture – end it. And, accountability is a principle, not a sentence handed out by a judge. Let’s be sure that it applies to state institutions: investigate Zerquera’s death.

With thanks to B. Arneson for editorial assistance.