This is the last in the current series of ‘World War X’ blogs, in which I summarize the argument so far.

‘World War Two’ has so dominated our thinking about world war that we can’t see clearly the nature of actual world armed conflict, historically or in the world today. The term ‘World War Three’ is used to refer to a geo-strategic conflict like World War Two. That terrible scenario is quite possible and much to be feared. But, I argue, we shouldn’t overlook the kind of world war we are actually in, and we should be aware that agendas to avoid, prevent, or deter, ‘World War Three’ can be used to justify the politics of what I call ‘World War X’.

If we broaden our lens, even slightly, to see world wars from different perspectives, we have the tools for understanding our current predicament more clearly. We can draw on a much longer history of global conflict and call it ‘World War Ten’. Or we can characterize it as a new kind of global conflict, ‘World War X’.

Every era demands its own theory of war, and world war, and hence peace and world peace. In the 20th century, the project of World Peace was designed around Europe’s Great War of 1914-18 and World War Two of 1939-45. We’re still living in the long 20th century, which didn’t properly take account of other types of world war.

War is a political activity. To clearly see World War X we need to understand logics of power. While most writers on changes in war focus on technologies of war-fighting—the weapons used and the organization of armies—my focus is on how the changing logics of political power shape changes in war. The strengthening logic of power as commodity germinated the seeds of war even while progress was made towards ‘world peace.’

I distinguish between two generic ways in which politics and war relate to one another. In ‘Schmittian’ war, enmity precedes and causes war, and war is organized as a clash between friends and enemies, over sovereign power. In ‘Hobbesian’ war, a generalized state of unregulated conflict prevails prior to particular hostilities. There are enemies because there is war, and those enemies can shift as the situation changes.

In both kinds of war, we need to focus on the ‘real politics’ of everyday political practices, as well as on how the political ‘rules of the game’ are set.

We also have to prize open the black box of ‘disorder’. Terms like ‘disorder’, ‘anocracy’ and even ‘nihilism’ are used as placeholders, substitutes for analysis. Ethnographies and histories of the real politics and experience of armed conflict show that many distinct things go under this heading—chaos, turbulence, lawlessness, disorder-by-design, incommensurability, revolutionary disruption.

I have argued that political power is shaped by three kinds of political logic—institutional, commodified, and ‘wild.’ These different logics of power relate to violence in different ways—and they also determine different logics of peace. There is also a feedback loop, in which armaments shape political thinking, and once war is underway, war develops its own relentless unthinking logic.

Political theory in the western canon is overwhelmingly a theory of the state—of how power is institutionalized. In these readings, violence is either deployed by a legitimate state authority (which may not want to recognize it as violence at all), against that authority (rebellion or civil war), or between states (war). Under this logic, projects for political peace consisted of combinations of Johan Galtung’s ‘negative peace’ (ending violence) and ‘positive peace’ (enabling people to achieve their potential through social justice).

The logic of institutionalized power determines a logic of peace that consists of peace treaties between states, and comprehensive peace agreements as new constitutional formulae for power sharing within states. Where positive peace intersects with liberal peace is that these lay the basis for social justice.

The 20th century project for world peace was the elimination of war as a legal category, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations. According to quantitative metrics for wars, for violence, and for human development, and according to the (less readily quantifiable) standard of normative progress, the world made tremendous advances.

That project is unravelling before our eyes. To understand why requires us to look at two other logics of power. We can see both at work in world wars previous to the 20th century—which is why it helps to see our current predicament as ‘World War Ten.’

A second, rival logic of power—in my analysis the most dynamic, the driving force in contemporary politics—is the commodification of power, a.k.a. the political marketplace. The quanta of power—political office, political loyalty, political services, even state sovereignty—are traded according to discernable market rules. Politics is business and business is politics. This was how European maritime trading empires were created and run. And it elevates kleptocracy to the organizing principle of politics. This forges a more ‘Hobbesian’ political world—‘friendship’ is transactional, and there are enemies of the moment, not of ideology.

Peace in the political market is a bargain among political business managers and entrepreneurs. It’s a security pact or a commercial deal, a profit-sharing arrangement. And it’s good for as long as market conditions prevail. That’s the contemporary version of ‘negative’ peace. It’s ‘positive’ peace only for those who play this particular money game.

It’s a logic of power shared across geo-strategic divides. The conventional realist security worldview sees geo-strategy—great power rivalry—as the driving force. I argue that, not that this doesn’t exist, but that it’s subordinate to geo-kleptocracy. ‘Negative’ world peace is a global shakedown by the geo-kleptocrats.

What has powered the commodification of power is an exponential increase in political money. Dirty money was the dirty secret of the liberal peace, late-colonial counter-insurgency, and the war on terror. But political spending’s biggest drivers have been corruption in Russia and the United States. It follows that power over making and regulating money is both the principal means of World War X and also the goal of winning it. Previous world wars were usually fought over territory and trade. Today’s is fought over the global currency regime.

In the 1940s, the sequence that led to the United Nations’ formula for World Peace began with global food security (the Hot Springs conference), followed by global monetary stability (Bretton Woods), and only then the United Nations charter, followed by the key pillars of the international legal regime. That sequence needn’t imply a structure, but it’s a useful indication of it. We need to affirm basic rights to food and what is indispensable for human survival, and—most crucially—reform today’s financial regime before we can reconstitute or salvage a ‘rule-based order’.

The final logic is ‘wild power’. To be precise, it’s an array of diverse forms of charismatic and autocratic power, along with contrasting forms, namely resistance to. and escape from state-based systems. In these logics, violence and authority relate in different ways—depending on which form of order or disorder prevails. Each has its counterpart practice of peace.

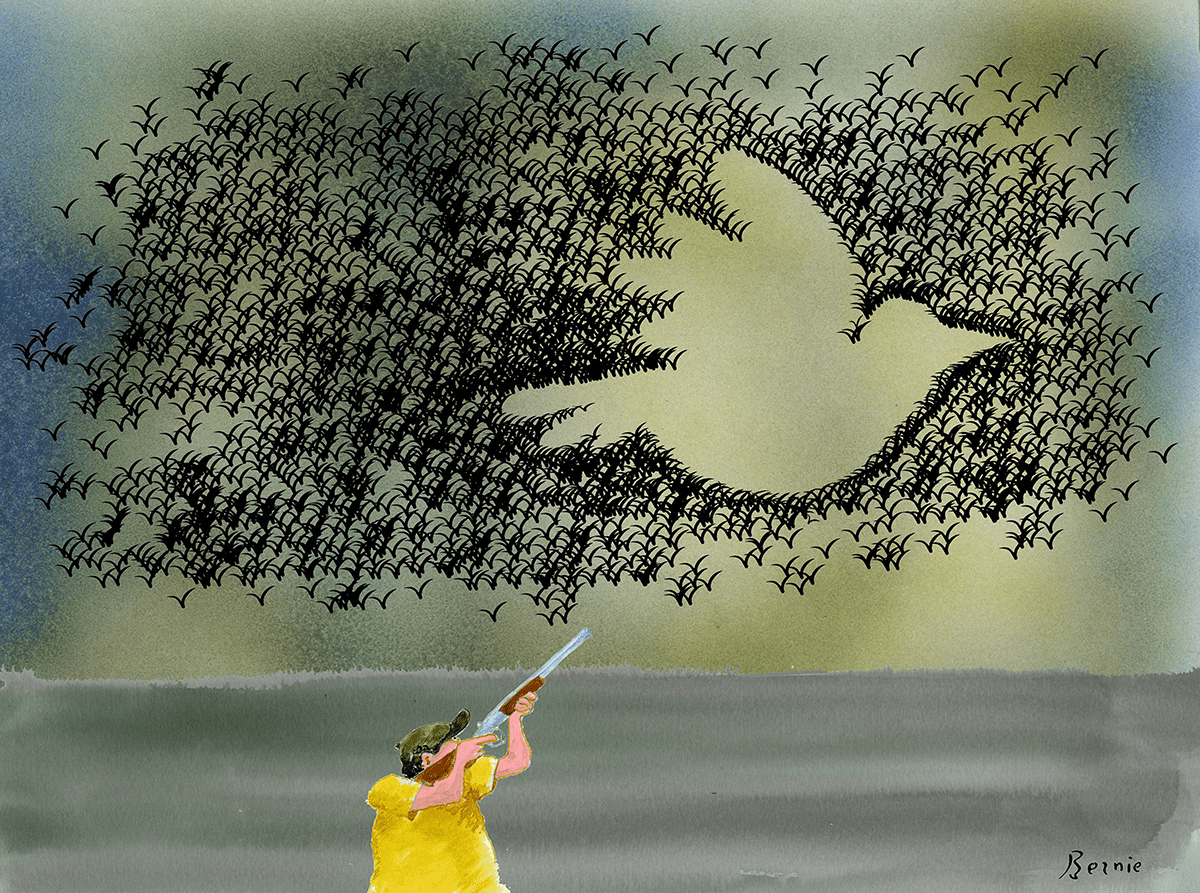

Particularly salient is the ‘heroic’ form of wild power in which acts of spectacular violence legitimize power. According to this heroic logic, war is a performance of violence. It can be spectacularly destructive—or just spectacular—and either way it is a contributor to several forms of disorder. Peace negotiations are performances too, in which the theater counts more than the substance. The same is true for third party mediation—its main aim is to provide a stage on which the peacemaker wins acclaim and legitimacy.

Wild power can be used to resist or escape institutional power and commodity power. The force of simple human solidarity can be extraordinarily powerful, though those who bring down dictatorships through civic protest need to have a theory and practice of real politics as well as one of resistance if they are to grasp and use the power that is theirs to take.

Wild power, combined with formal political instruments such as a political party and political money, can capture state power. When heroic violence is fused with power-as-commodity, we have the spectacle of world leaders operating as disruptive corporate CEOs, combining almost unlimited political budgets with communicative excess and spectacular violence.

The logics of commodity power and wild power have subordinated but not eliminated the logic of institutional power. States are still in full possession of the legacy of massive armed forces, weapons systems, surveillance systems—and the security cultures that go along with them. The arms business, while justifying itself on the grounds of ‘national security’, is run by transnational corporations looking for their bottom lines. Nuclear weapons are proliferating, and normal accident theory predicts that, sooner or later, they will be used—accidentally, recklessly, or with deliberation. Within World War X there’s an ever-present risk of ‘World War Three’—a large-scale conventional war—a danger that is exacerbated by dominant security doctrines that dictate greater spending on weapons and weaponizing every available technology.

Today’s peacemaking is mostly cutting deals that may pause warmaking but don’t bring about any form of political order. They create non-war, for a while, but aren’t sewn into a tapestry that delegitimizes warmaking.

How do we find a route back to world peace? It begins with how to manage the real politics of each of today’s versions of ‘negative’ peace: state-based peace treaties and proto-constitutional peace agreements; marketplace peace deals and pacts; and peace performances and prizes. Anyone interested in peace has to engage with these.

It continues with addressing the centers of gravity of the driving logics: unfettered political money and the delusional hubris it can generate. There cannot be world peace without tackling these macro issues, through politics and law.

And there’s also the work of peace from below—civics and civility, humanity and human connections, foundational justice.