Ethiopia’s struggle with increasing popular demands for political and civil rights, and governmental transparency may have reached an important turning point. On January 3, 2018, the country’s Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn made a surprising announcement: the government would release political prisoners and close the notorious Maekelawi detention center. The prison, he also announced, would be turned into a ‘modern museum.’

Much attention was riveted by the political implications of the announcement. Despite welcoming the change, in usual style, Ethiopia-watchers and analysts expressed some wariness about what the move ‘really’ meant: a victory for political opponents (especially Oromo), an indication of state fragility, a sign of the government’s concerns about outside meddling and need to get its own house in order, a desire to avoid distractions from its Renaissance Dam project, recognition that political upheaval was its most serious development threat, or indication that the ruling coalition the EPRDF was facing serous internal upheaval as political party members the ANDM and OPDO were not willing to play junior members to the dominant TPLF. The political opposition, while quick to dismiss the PM’s statement, found something to applaud in the EPRDF party members’ statements. Lidetu Ayalew, founder of opposition Ethiopian Democratic Party (EDP) noted: “Previously, EPRDF had been externalizing problems and blaming anti-peace forces. But now, it is a welcome move by the Committee to accept the seriousness of the problem.” How the decision will be carried out is an on-going story, with some backtracking from the PM, but apparently prisoners are being released from Maekelawi.

Less attention was drawn by the decision to transform the prison into a museum. The idea seems to have begun in an editorial printed by the Addis Standard on June 28, 2016. There, the magazine’s editors described the prison as: “a legal black hole that was never made subject to public scrutiny; it remains beyond and above any form of accountability….[and] a symbol of a regime that acts contrary to the values, principles, and rules of the constitution it championed.” The article argues that that how and why the prison continues to function in this way is a betrayal of the country’s constitution and federal divisions of power. A return to and re-animation of the building blocks of Ethiopia’s political dispensation, the piece asserts, is capable of guiding the country forward. The prison, the authors argue, belongs to the past: “Ma’ekelawi should be a place to remember the past and not to live the present.” They cite the examples of other countries (Kenya, South Africa, Senegal, and Poland) that have undertaken a transition from conflict or authoritarianism, and as a symbol of dismantling an entire structure of repressive institutions and practices, converted detention centers into museums.

The authors might also have cited Ethiopia’s own diverse museum and memorial history.

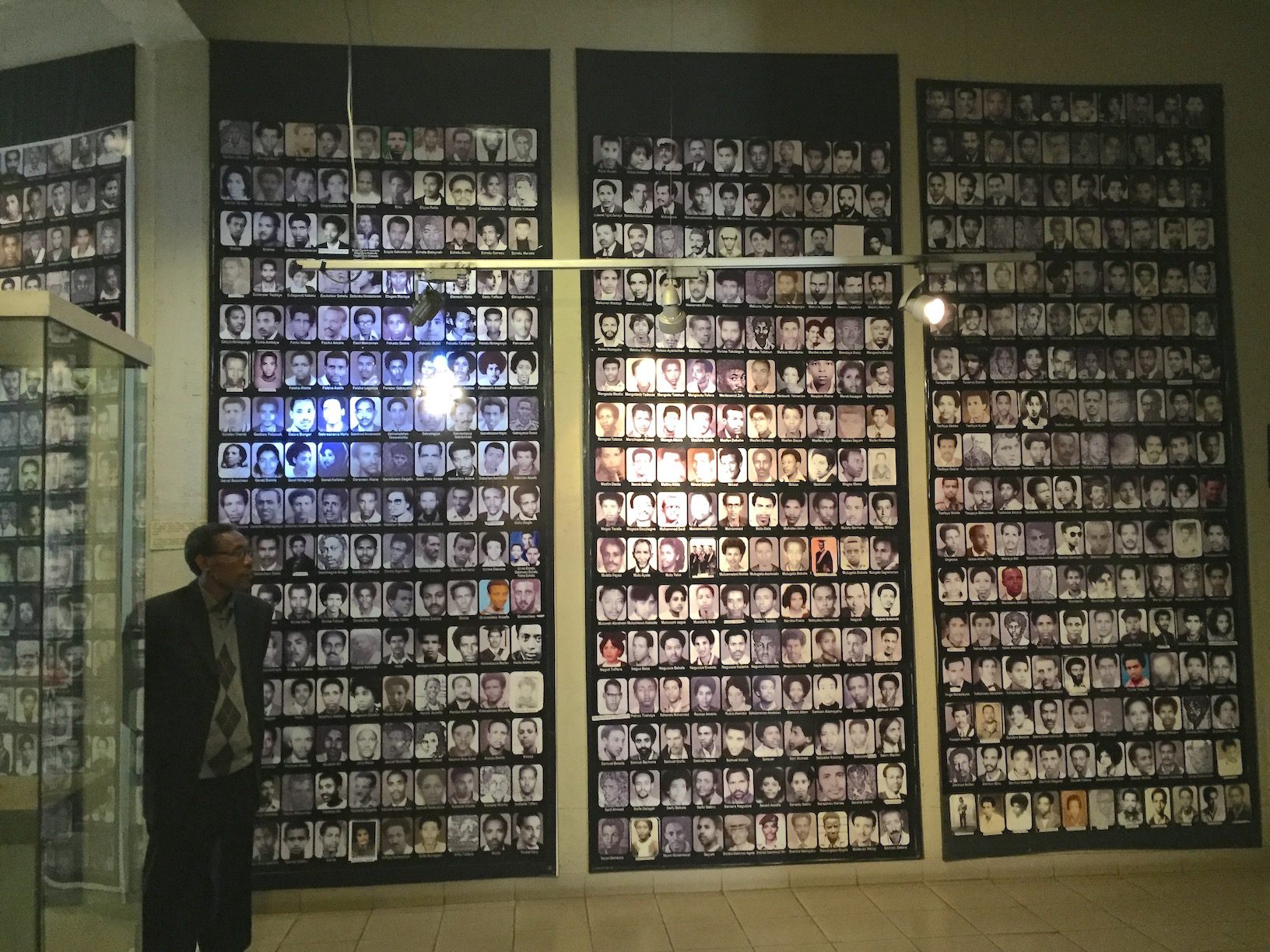

RTMMM docent and survivor of the Red Terror, Muluneh Haile. (Bridget Conley/World Peace Foundation 2016).

Addis is home to several memorials that highlight authoritarian violence. Among them are Yekatit 12 memorial in Sidist Kilo, commemorating a massacre perpetrated by Italian forces over three days in 1937, that is estimated to have resulted in 20,000 deaths in Addis Ababa, and as the Italians inflicted punitive measures across the country.[i] Another, is the small memorial to the 60 ministers of the Imperial government who were slain in 1974, during the rise of of the military regime under Mengistu.

A third, more expansive memorial and museum can be found in the Red Terror Martyrs Memorial Museum (RTMMM) which offers an extended historical narrative of the rise of the military regime, and the period of extensive violence against the urban opposition during the Red Terror. These examples follow logics of commemoration and mourning, presentations of the human losses inflicted on a society by an oppressive regime.

There is a prison memorial museum in Addis that is notable by its absence. On the edge of the African Union’s headquarters, one of Ethiopia’s most infamous prisons once stood, “Akaki” or, as called by Ethiopians, “Alem Bekagn” – farewell to the world. Built by the Italians during their occupation of the country, it later housed victims of the Red Terror and other political prisoners. It was torn down to make way for a new Chinese-built AU building, and an effort to mobilize support for transforming the now flattened site into an African Union Human Rights Memorial (AUHRM) never came to fruition. (Access essays from 2012 – 2013 in support of the AUHRM on this blog).

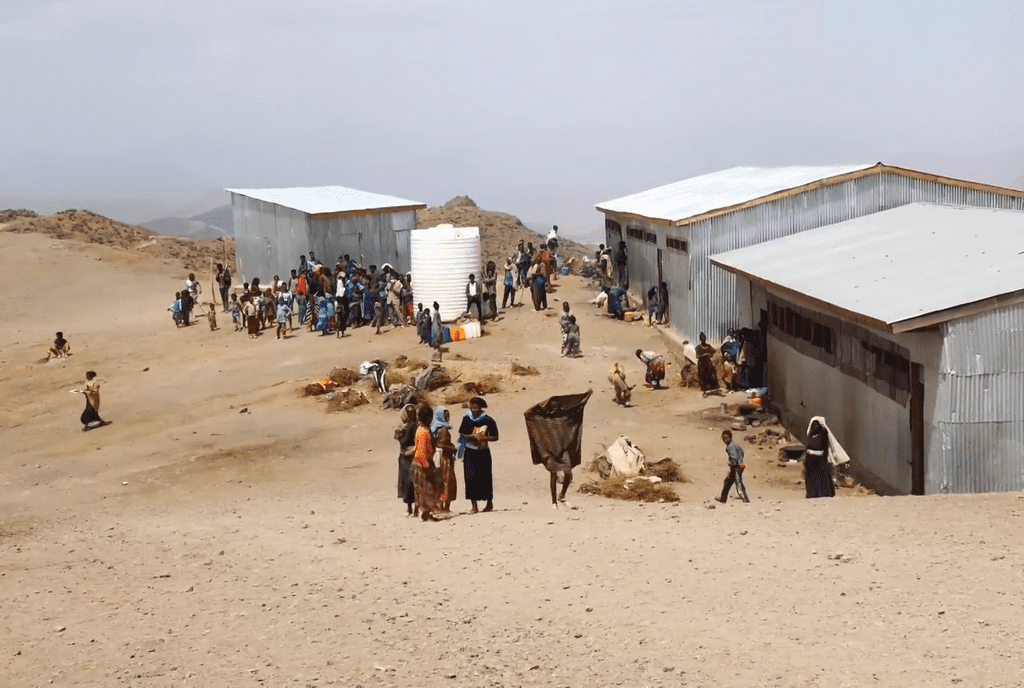

If one moves outside of Addis, there is another Ethiopian memorial model that developed during the transition following the defeat of the Mengistu’s regime: regional memorial and museums dedicated to the history of the members of the EPRDF in their efforts to win the war, bolster national culture and political unity, and create political parties responsive to the people’s needs. Two of these museums are complete and their exhibition narratives attempt to capture the idealism that sparked and continued to fuel the effort to overthrow the military regime, despite enormous hardship.

Soaring monument at the Tigray Martyrs Memorial Museum and Monument in Mekele. (Bridget Conley/World Peace Foundation, 2017).

The Tigray Martyrs Memorial Museum and Monument occupies high ground, visible from across the expanding city of Mekele, the capital of Tigray. Its memorial soars into the sky and its exhibitions tell a story of the social and political role of the TPLF alongside the war story: their communications, humanitarian programs, educational work, political debates, agricultural developments, cooking, conferences, and health programs are woven in and out of scenes of military units. The development of the party, the armed movement, and the nation emerges as a single story. This was a ‘people’s war’: military strategy included social and political development.

The Amhara Region Peoples Martyrs Memorial Monument shares many similarities in purpose and narrative style with the museum in Mekele, but angled towards its Amhara audience. Paid for by the Amhara Regional Government, the grounds include an amphitheater, museum, library, art gallery, monument, meeting halls, and cafeteria, spanning a hilltop on the banks of the Blue Nile, just as it leaves its source, Lake Tana. Its exhibition displays the evolution of the armed movement in tandem with cultural, ideological and social development of the party. Both the exhibitions in Mekele and Bahir Dar display then now established parties and leaders as young upstarts, who claimed for themselves a role in changing their country. One can argue with points of the narrative, which clearly, like most national museums, paint the picture of how powerful interests want to see themselves. But embedded within the aspirational narrative is a compelling presentation of idealism that sustained them.

Photo of a wartime cultural event, displayed at the Amhara Region Peoples Martyrs Memorial Monument (Bridget Conley/World Peace Foundation, 2017).

The Oromo memorial site was begun along similar lines to both the Amhara and Tigrayan memorials, but the process was stopped short, when the capital was moved from Adama, where the site stands, to Addis. A museums was never completed, the process interrupted development reflects tensions between the Oromo and the EPRDF. Nonetheless, the memorial, which is finished, perches on a hill that is visible from across Adama, it is composed of two sweeping white pillars, arched towards the sky, meeting at a point of two circular structures that touch each other. Underneath are two pairs of smaller, arching stone structures, and on the ground, a white dome. It gestures to an abstracted human skeletal form: legs and ribs, representing the struggle of the people for freedom, to preserve their culture, to point to the future.

Together, these structures, mounted during the period of profound political transition following military defeat of the former regime, provide a memorial landscape of the transition from military authoritarianism to the aspirations of the EPRDF-led government, grounded in development and ending poverty. It was a period of momentous national political, social and economic change–marked by the creation of a new memorial landscape.

Is now the time for a new momentous transition–one with replete with new memorial museum structures? That the government put forward the idea of transforming Maekelawi into a museum should be taken as a sign of hope. Once its current occupants finally vacate the rows of cells and the ‘investigations’ (including torture) cease, the prison memorial museum can take its place; allowing visitors to freely access a place that epitomizes control, surveillance, coercion and lack of transparency. This museum could capture a different and hopefully new moment. Perhaps as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is intended to symbolize the country’s future-oriented developmental aspirations, a new prison memorial museum might symbolize a shift to a less coercive, more transparent and fair political dispensation. If it is possible for the government to gather the sense of purpose and commitment to transform itself into a more democratic posture—a rare evolution to occur without some form of extreme external pressure—then such a museum could find meaning and be a site for making meaning into the future.

Transforming a prison structure to fit a new purpose is fundamentally easier than transforming how a state functions, but it is not a bad place to start.

Notes:

[i] Campbell 2017, 327.