“If you were Truman, would you have dropped the bomb?” It’s a question I’ve heard countless times, in settings ranging from classrooms to dorm rooms to happy hours. Each time, the question is followed by the same stale arguments, neither original nor insightful. The phrases “necessary evil” and “the benefits outweigh the costs” are thrown around, and the only constant more predictable than these tropes is the tone they are spoken in: cold and detached, as though emotion would be a weakness. The discussion becomes a casual, rhetorical debate about whether or not the killing of upwards of 100,000 civilians – from the immediate impact alone – was justified.

In the almost eighty years since the use of the bombs, numerous attempts have been made to reckon with its legacy. For example, in the 1990’s, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum planned an exhibit to showcase the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb. The exhibit aimed not to glorify the plane, but to center the experiences of the victims, and to demonstrate to the world the scale of the destruction. In response to the planned exhibit, the Air Force Association mounted so much opposition that the exhibit as planned was canceled, and the museum’s director, Martin Harwit, was forced to resign. Even at the fifty-year anniversary of the war’s end, the primary reason for their opposition was concern that the exhibit was “revisionist,” and would invoke “sympathy” for Japan, rather than cementing the plane as a symbol of national pride.

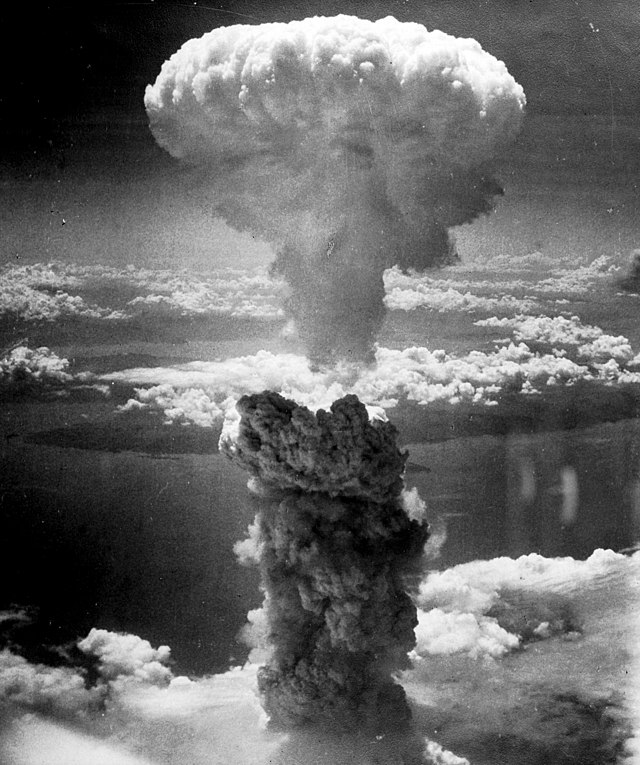

When commemorations have taken place, such as the case of University of Chicago in 2017, they have often failed miserably. UChicago remembered the anniversary of the first nuclear chain reaction by setting off a rainbow mushroom cloud, designed by Cai Guo-Qiang, a famous pyrotechnic artist. In theory, the event was meant to kick off a week of reflective debate and conversation. In practice, it’s unclear how anyone seriously believed that a rainbow fireworks display would be seen as anything but celebratory.

The release of Oppenheimer brought with it another opportunity for reflection on this history, but ultimately fell into a similar pattern. Christopher Nolan, who wrote and directed the film, chose not to show the bombings themselves, saying that the film was a biopic, not a documentary. He intended to remain true to Oppenheimer’s experiences, and since Oppenheimer himself did not witness the bombings, they were not included in the film. While some saw this decision as a sign of respect for the victims, respect didn’t move Nolan to find any other ways of including Japanese perspectives. The result is that the complete lack of Japanese representation in the film allows US audiences with no connection to Asia to walk away thinking of the bombs like large segments of the American public did at the time: as a mass destruction that happened to them, over there. The real danger of nuclear weapons is expressed in fear of what might happen to us in some distant future attack. It goes without saying that Oppenheimer was tortured by the impact of his bomb, but in the film, the only suffering presented is white suffering – internal agonizing and fear of hypotheticals. Even when he imagines the aftermath of the bombings, he can only picture the bomb’s impact on white bodies.

Perhaps that was the point. But even so, the omission of not only the Japanese (and Korean and Chinese) bomb victims, but also the incarceration of Japanese Americans and the displacement of Hispanic and Indigenous people from Los Alamos, is more than a failure to center those most affected. By neglecting to address these histories, the film sterilizes the past and obscures the racial dynamics that shaped the decisions related to the bomb, from its creation to its use. The film then portrays both sides of the scientific and defense communities’ disagreements on the bomb’s use, but its failure to contextualize or challenge the flawed and often racialized assumptions that led to the use of the bomb ultimately frames these discussions as just that: debates. Like Oppenheimer himself, the film delivers a dire warning for the future, but fails to take accountability for the past.

I am not interested in participating in or legitimizing the debate on the use of the bombs. Many before me have demonstrated that the decision was inhumane, strategically unnecessary, and influenced by racism.[1] Instead, I argue that it is time to re-evaluate Americans’ insistence on continuing these debates, and by extension, defending and justifying the bombings. Why is it that awe and morbid reverence at the science behind the bombs so often overshadow horror at the destruction they have caused? These cold, intellectual conversations feel no more connected to reality than the infamous trolley dilemmas that so often haunt Ethics 101 curriculums.

I never had the privilege to engage in these debates with academic detachment. I grew up hearing about how just before her twentieth birthday, my grandmother lost her home in the US firebombing of Tokyo. As I grew older, I began to wonder if the anxiety that plagued her throughout her life was rooted in that trauma. When I was twenty, I visited the temple where she took refuge the night that the US bombed her home. When those around me insist on coolly and rationally debating the atomic bombings, I picture my grandmother in that temple, which wouldn’t have stood up to firebombing, let alone an atomic explosion. It’s harder to engage with a trolley dilemma when your own family is on the tracks.

There comes a point where insistence on debating the bombings becomes violent in itself. To justify an atrocity of this scale requires directly or indirectly dehumanizing its victims –and this dehumanization has concrete consequences. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, hate crimes against Asians and Asian Americans have increased. Many have rightfully pointed to the roots of these crimes in xenophobia, immigration policy, and orientalism. But in a world where every year, people insist on defending atrocities committed in Asia, how are we surprised that this violence has become normalized?

Perhaps the continual need to debate the atomic bombs represents a debate that this country isn’t yet ready to have. The ongoing resistance to accountability for the use of the atomic bombs is not a stand-alone issue: it is rooted in the same systems of white supremacy that fuel other examples of historical revisionism (e.g.,slavery, the Civil War, and the genocides against indigenous peoples). Given the choice between critically reflecting on the racism embedded in these past decisions, and finding ways to justify atrocities in order to maintain national pride, many Americans’ choice has become clear:

It is easier for some to deny the humanity of a former adversary than it is to confront the inhumanity of our own past. Only through centering the voices of those most impacted that can we truly understand this legacy, and its implications today.

Elizabeth Smith is a Research Assistant at the World Peace Foundation and a second-year MALD candidate at the Fletcher School, concentrating in Gender and Intersectional Analysis. Prior to Fletcher, she produced documentary content for a media startup in Tokyo and conducted a Fulbright in Seoul, studying the intersections between gender, memory, and social movements in Korea. She holds a B.A. in Law, Letters, and Society from the University of Chicago.