In 1984 Ethiopia was stricken by a terrible famine that killed as many as a million people. In 2024 Ethiopia may be stricken by a terrible famine that could kill as many as a million people.

This blog post draws some parallels between the two, ending with the transcript of part of hearing on the Ethiopian famine in Britain’s parliament in 1984, which is a regrettably timeless commentary on the indifference of politicians to human suffering.

Warnings

In 1983 and 1984 aid agencies and the Ethiopian government’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission repeatedly warned of looming calamity. But it was only in October 1984 that the true disaster of the famine was revealed, in a famous BBC news report from a relief camp in the town of Korem. Shortly after that, Bob Geldof brought together musicians under the banner ‘BandAid’ and released a record, ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’ This became the LiveAid concert a few months later. Shamed into action, western governments provided aid and the Ethiopian government permitted them to operate.

In October 2023, reports from UNOCHA and USAID’s Famine Early Warning System sounded the alarm. On the five level scale of food insecurity, from phase 1 (normal) to 5 (catastrophe or famine), FEWSNET predicted a fast-expanding number of people in phase 4, ‘emergency’ by early 2024. One step short of outright famine, these levels of hunger are still bad enough for children in the poorest families to begin dying of starvation.

Priorities

In 1984, the military government of Ethiopia, known as the Dergue, was fighting multiple wars. It had the largest army in sub-Saharan Africa and was spending its scarce resources on weapons, logistics and the upkeep of this massive force.

In 2024, the Prosperity Party government of Ethiopia, is fighting wars in Amhara region and parts of Oromo region and is rattling its saber, threatening armed conflict with its neighbors. In 2022 (the last year for which figures are available) its military spending topped US$1 billion, double the previous five years. Last month, Ethiopia gave its highest award to the CEO of the Turkish drone manufacturer, Baykar, which sold its weapon systems to the country.

In 1984, the then-government spent lavishly on the ten-year anniversary celebrations of the revolution that overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie, which was also the launch of the new Workers’ Party of Ethiopia. Huge monumental arches were built on the road from the airport to the city center and around Revolution Square (previously and later known as Meskel Square) where the leader of the junta, Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, took the salute from vast parades of soldiers. The arches were a donation from North Korea.

Ironically, a famine played a key role in bringing down Haile Selassie—a famine that the emperor chose to forget. Radical students clipped together footage of the Emperor’s lavish 80th birthday party with scenes of starving peasants, accusing the ruler of being a thief. The lesson that the Dergue learned was that the story of hunger was the problem, not the hunger itself.

In 2024, the current prime minister has set aside at least US$ 10 billion for a lavish new palace in the hills outside Addis Ababa. He has told the parliament that it was funded by his ‘personal drive’—the donor is widely believed to be the United Arab Emirates.

Denials

In 1984, the Ethiopian government played down the food crisis. It suppressed news entirely in the critical months of April-September, when it was preparing for its tenth anniversary celebration of the revolution and the launch of the new party. Documenting these denials is a major part of the section on Ethiopia in the Article 19 report.

In February 2023, the Prime Minister proudly announced that Ethiopia was self-sufficient in food:

Our laser focus on wheat productivity is bearing fruit and our ambition to begin exporting wheat this year has already materialized. A great achievement for Ethiopia and an even great achievement for our continent.

A few weeks after PM Abiy’s boast about food exports, aid workers uncovered large-scale theft of food aid. After USAID and the World Food Programme suspended their distributions, a Washington Post investigation into the scandal reported a diplomat saying that ‘Flour made from donated wheat was being exported to Kenya and Somalia even as Ethiopians starved.’

Nonetheless, PM Abiy stuck to his line. Ethiopia’s food production and export triumph was parroted by the Minister of Agriculture in September. Not only had the wheat scandal been exposed but the failure of the main 2023 harvest had become apparent at this time.

Compare the situation exactly eight years earlier, when the ‘worst drought in decades’ struck, and Ethiopia promptly released US$300 million for food imports and pledged a further US$700 million, that was not in the end needed because the donors, confident in the government’s capacity and determination, stepped up with the remainder. A multi-donor assessment of the 2015-2016 relief effort concluded:

Despite its impacts, with the current drought estimated to be most likely a one in several hundred years event (a rarity that would place significant strains on most public services), the lower impact of this drought compared to those in 1984 and 1973 is a testament to the advances being made in improving the resilience of Ethiopians to climate shock and stresses.

Those improvements have since been reversed. In December 2023, when the Tigray regional authorities sounded the alarm and called for urgent aid, the central Government dismissed the report as ‘completely wrong.’ In January 2024, it began to backtrack—but insisted that it had ‘the necessary experience, expertise, and established structures and they are ready to deliver.’

Aid donors still seem ready to give the Ethiopian government the benefit of the doubt.

Excuses

In 1983-1984 international donors offered a litany of excuses for not responding. The port could not handle the volumes needed. The figures were made up. Everything seemed fine in Addis Ababa. The government couldn’t be trusted to handle aid. These are recounted in, among others, Peter Gill’s book A Year in the Death of Africa (1986) and the Article 19 Report.

In 2023, the biggest donors—USAID and the World Food Programme—uncovered an enormous, well-organized scheme for stealing food aid. The Washington Post quoted an unpublished report by the Humanitarian Resilience Development Donor Group:

Extensive monitoring indicates this diversion of donor-funded food assistance is a coordinated and criminal scheme, which has prevented life-saving assistance from reaching the most vulnerable …. The scheme appears to be orchestrated by federal and regional Government of Ethiopia (GoE) entities, with military units across the country benefiting from humanitarian assistance.

Attempts to pin the blame on low level officials in Tigray were an obvious diversionary tactic, though the Tigrayan authorities identified 186 suspects and detained seven for their role in the loss of 7,000 tons.

The bigger story was massive coordinated theft across seven of Ethiopia’s nine regions that had been going on for years. Some WFP officials made no secret of their sympathies for the government. A diplomat quoted by the Washington Postsaid that WFP was ‘negligent or complicit’ in the aid theft. Reports of investigations by USAID and the UN haven’t yet been released.

When the scandal broke, USAID and WFP promptly suspended their food distributions—even though people were starving to death. Six months later resumed only on a pilot scale in November, promising a gradual scale up into early 2024.

The October FEWSNET report contains the following words, a masterpiece of understatement:

The gradual resumption of food assistance deliveries by early 2024 is expected to moderate the size of kilocalorie deficits among beneficiaries, but not yet at a scale and frequency that would prevent high levels of food insecurity.

As of mid-December, the 2023 response plan—you read that correctly, the emergency aid plan for last year—was only one third funded. And aid donors, especially USAID which is the biggest, are still planning on cutting aid to Ethiopia for 2024.

The UNOCHA update of 10 January includes this sentence:

Donors must frontload funding to scale up the response this January; money received from March-April 2024 will be too late for many as suffering & destitution will have deepened.

Déjà Vu

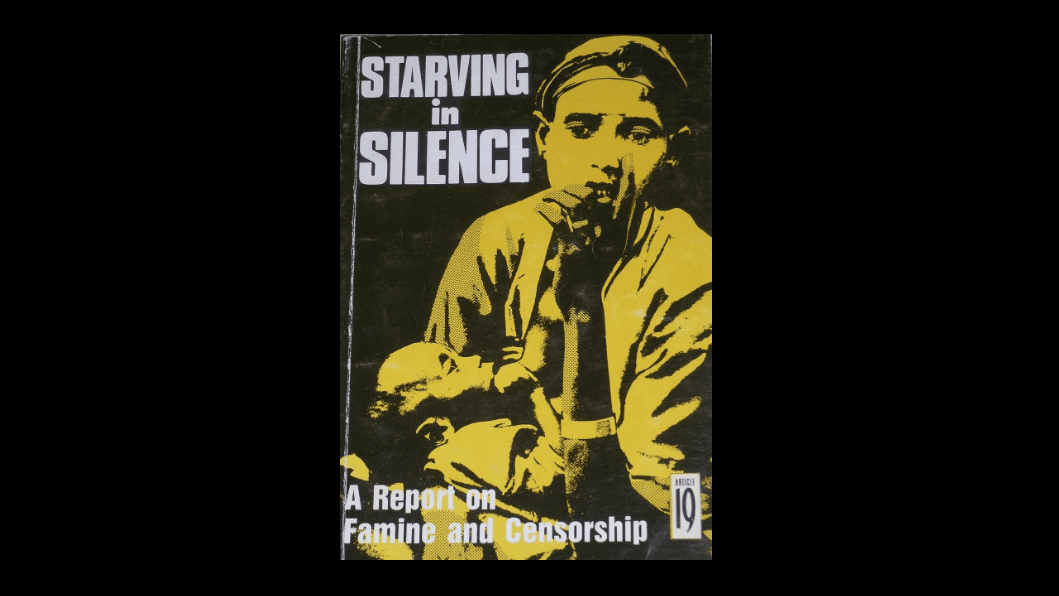

The following is an excerpt from Article 19, Starving in Silence, (1990) pages 91-93:

On 21 November 1984, the UK House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee summoned representatives of Oxfam and the Save the Children Fund (SCF) to Westminster to interview them on the famine in Ethiopia.

The famine had become urgent international news on 23 October due to the BBC-Visnews film by Michael Buerk and Mohamed Amin of the feeding centre at Korem. As the world press clamoured to interview representatives of British aid agencies on the famine, the British government was embarrassed by its near-total inactivity. As the meeting drew to a close, Sir Antony Kershaw, chairman of the committee, became increasingly flustered and angry. Why, he wanted to know, had the British government been kept in the dark about the impending famine? He questioned Colonel Hugh Mackay, Overseas Director of SCF.

Sir Antony Kershaw: Why do you not tell the British embassy there [in Ethiopia]?

Col. Hugh Mackay: We do and we maintain close links with the embassies, but I come back to that rather curious phenomenon that people will not believe a famine until they see it.

Sir A. K.: That is not my question. I was asking why your people do not tell the British embassy who can pass it on [to London]?

Col. H. M.: We do tell them and that information is discussed in great detail at regular intervals with High Commissions and with embassies.

Sir A. K.: Did you say that they did not believe you?

Col. H. M.: I’m afraid not at this stage, sir.

Sir A. K.: Are you saying Save the Children Fund is not believed by embassies?

Col. H. M.: In this particular field, Sir, in this particular centre, in this particular stage of trying to predict a famine, at this stage, no.

Sir A. K.: Can you give me examples of where you predicted a famine and the British government did not take notice?

Col. H. M.: Sir, the Ethiopian famine which in our reckoning started two years ago.

Sir A. K.: Did you report it?

Col. H. M.: Yes.

Sir A. K.: Then?

Col. H. M.: They did fuck all, Sir.

[Pause]

Sir A. K.: How do you know nothing was done about it?

Col. H. M.: They did believe us, let us say, but their response was slightly negative.

In the official records of the meeting, Col. Mackay’s response to the penultimate question has been rendered simply as ‘yes, Sir.’