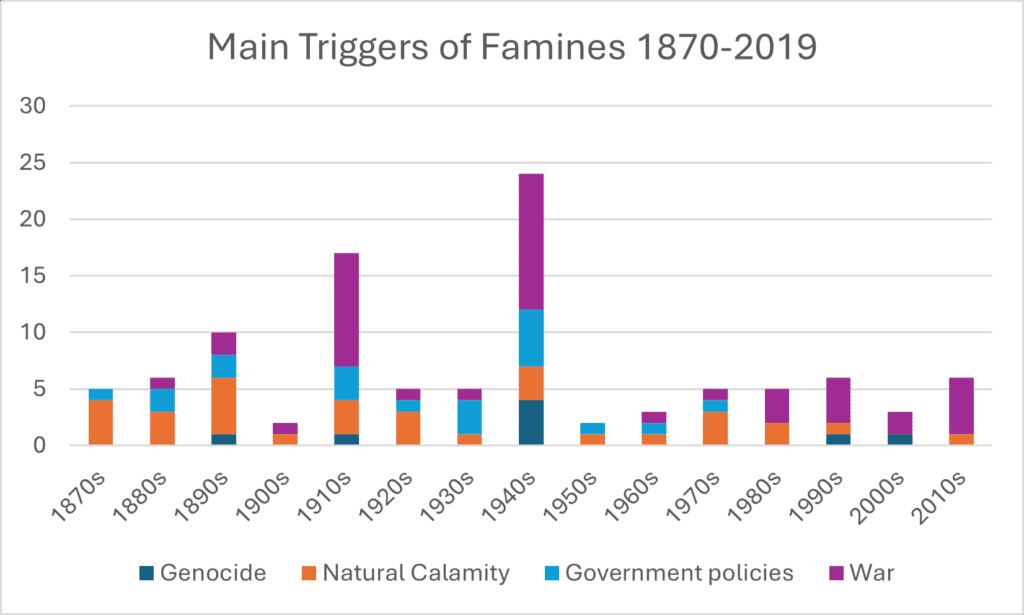

World War II saw the greatest spike in the number of episodes of famine and mass starvation in history. It figures prominently in the World Peace Foundation historic famines dataset with no fewer than nineteen entries in seven years, out of 89 total over 154 years, leaving more than 20 million dead. They include four of the eight classified as genocidal starvation “first degree famine crimes”.

The Nazis’ starvation of the Jews in the Polish ghettos occupies a special place in this appalling chapter in the history of famine. Our dataset classes this as a genocidal famine along with the murder by starvation of Jews in Auschwitz and elsewhere during the Holocaust. Focusing on the two biggest ghettos, in Warsaw and Łódź, the bare facts are as follows.

The first ghetto, in Łódź, was established in December 1939, and sealed. It concentrated 164,000 Jews in a tiny area of just 1.6 square miles. A further 40,000 Jews and 5,000 Roma were dispatched there. There were five hospitals and physicians and administrators kept scrupulous records so far as they could. The average calorific availability was 1100 kilocalories per person per day, about half of the minimum required for a human being to survive.

The central element of this starvation crime was restriction on rations. This was first documented by Raphael Lemkin in his famous 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (see pages 87-88). The Nazis imposed a hierarchy of rations with Jews at the bottom. The ghetto diet was initially designed as a prison diet, though the amounts soon fell below. In his authoritative book, The Destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg writes: “One implication of this design is unmistakable: the Jews were no longer guaranteed enough food for survival.” (p. 264)

Moreover, the food was not divided equally. While the Germans determined the overall supply of food—and were therefore guilty of the starvation crime—the ghetto’s Jewish council (Judenrat) were required to allocate, and hence prioritize, the rations. No rationing system ever operates without leakage, and those who ran the soup kitchens were unlikely to go hungry. An estimated 45,000 people were murdered by starvation and disease and almost all who survived were transported to death camps. Łódź was the last ghetto to close, in 1944.

The Warsaw ghetto was established in November 1940. It was the largest by population, with 460,000 people concentrated into a tiny section of the city—about 1.3 square miles. Unlike Łódź, which was completely sealed, food could be smuggled in and there was a black market. Average calorific availability is harder to calculate because of smuggling. Hilberg cites Jewish ghetto doctors who estimated that the end of 1941, council workers averaged 1,665 kilocalories per day, artisans 1,407, the “general population” 1,125, and the least fortunate merely 800, with children already starving to death (p. 270). Not even those at the top of the ghetto’s “food pyramid” had enough. Over the following year, available food contracted to just 800 kilocalories per person per day in total, little more than one third of a minimum ration.

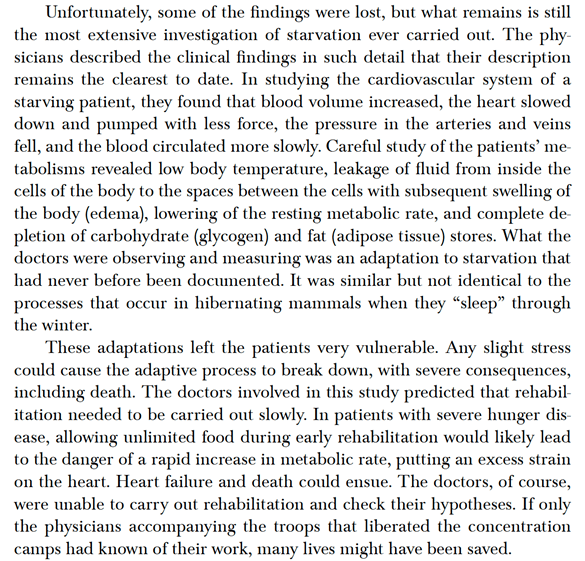

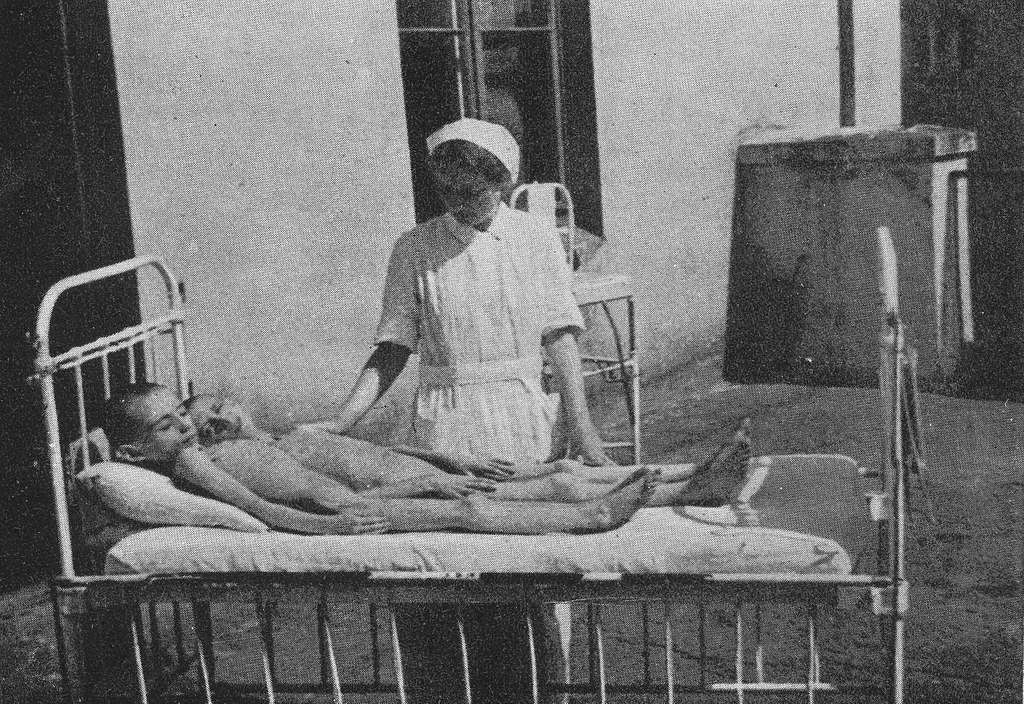

The ghetto had two hospitals—one for adults, one for children—which were acutely short of basic supplies. Defying the German ban on medical research, a remarkable group of Jewish physicians undertook pioneering studies of starvation. They documented the effects of starvation on the human body in what was a horrific, unparalleled laboratory.

Part of the Jewish doctors’ rationale was to improve treatment, and part was to document the Nazi crimes for posterity. In an article on the research, the distinguished physician and nutritionist, Myron Winick writes (p. 104):

On July 22, 1942, German army units entered the ghetto and attacked the hospitals. Patients and some of the doctors were killed outright or deported to the death camps, and the laboratories were destroyed. The physicians hid a copy of their precious manuscript, which was smuggled out and later published, along with some of their photographs.

A French translation, entitled ‘Maladie de Famine’ (‘The Disease of Starvation: Clinical Research on Starvation in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942’) was rediscovered in the Tufts University library three years ago.

According to different estimates, the Nazis murdered between 83,000 and 100,000 people through starvation and disease in the Warsaw Getto. In 1942, they began deportations to the death camps. Following the uprising in May 1943, the Ghetto was razed and closed.

Across the Polish territories there were a dozen other ghettos of significant size and more than 200 places in which Jews were concentrated.

The total number of Jews killed by starvation and disease over the years 1939-45 is difficult to enumerate. Hilberg cites an SS statistician’s number of 762,593 for the overall “Jewish population deficit” in the Polish territories, in addition to those murdered during deportations and in death camps (p. 274). Many of those were victims of hunger and disease. In addition, at least half of the prisoners in Auschwitz labor camp were murdered through starvation. If we include victims of hunger from other Axis-occupied territories, the Nazis killed somewhere between 700,000 and 1.1 million Jews by starvation in the course of the Final Solution.

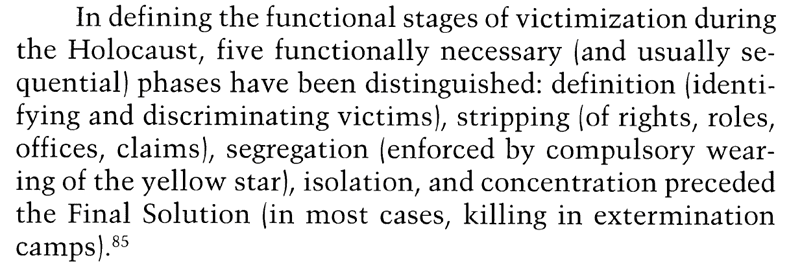

In her influential paper ‘Genocide by Attrition,’ Helen Fein describes the Warsaw Ghetto as ‘epitomizing’ how starvation and disease can be instruments of slowly creating conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction of the targeted group. In a section entitled ‘The genocidal process and public health’, she begins with an overview of the stages of the genocide (p. 31):

Fein’s key point follows:

In line with Lemkin, Fein is adamant that the ghettos were genocidal.

Fein focuses on the incremental, painful deaths by starvation and disease. What she doesn’t explore is how starvation began to rip apart the social fabric, for example, how the Judenräte were compelled to become instruments in implementing rationing, and the smallest increments in food entitlement turned victims against one another. Hilberg touches on this: “As ghetto hunger raged unchecked, a primitive struggle for survival began… The ghetto Jews were fighting for life with their last ounce of strength. Hungry beggars snatched food from the hands of shoppers.” (p. 272) And for those shoppers, the basic, biological need for sustenance plunged them into the “gray zone” where their minds and morals were preoccupied with the quotidian cruelties of selfish survival.

The ghettos were part of the Holocaust. However, there is a disagreement among historians as to whether the larger ghettos, such as Warsaw and Łódź, were intended, at the outset, as a step towards the killing of all Jews, or whether they were initially set up to serve a transitional stage en route to the transportation of the Jews to Madagascar (or another colonial territory), and became an intermediary stage for concentrating Jews in preparation for the death camps only after the Wannsee Conference of January 1942.

There’s also a debate as to whether those who administered the ghettos were all of one mind, even after Wannsee. Christopher Browning in The Path to Genocide, examines the reasons why the bureaucrats and physicians enforced the ghettoization policies. Some were ardent Nazis who eagerly supported Adolf Hitler’s Final Solution. Others energetically implemented plans to make the ghettos economically productive or to isolate the confined population from the Polish and German populations, on the grounds of public health—and for those reasons pushed for more food to be provided. He examines several of the men who administered the ghettos (p. 133):

[Hans] Biebow explicitly opposed [Alexander] Palfinger’s suggestion for presiding over a “rapid dying out of the Jews” through starvation. [Harald] Turner renewed his request for deporting the surviving Serbian Jews even as the Wehrmacht firing squads were clamoring for more Jews to shoot in order to full fill their obscene reprisal quotas. Certainly the expulsion of millions of Jews to Madagascar would have involved catastrophic mortality but [Franz] Rademacher was more feckless than cynical when he envisaged his Madagascar “super ghetto” as proof of Germany’s “generosity” to the Jews that could be exploited propagandistically.

Browning argues that some German administrators wanted to keep the Jewish population just short of famine, and that the “ongoing horror and attrition in the ghettos was not the result of a ‘set task’ of cynical ghetto managers but were problems they could not overcome.” (p. 42) This overlooks a point that he makes later, which is that famine doesn’t afflict everyone equally: “The food pyramid in the Warsaw Ghetto was in fact an array of the population in the order of their vulnerability to debilitation and death.” (p. 270)

The “food pyramid”—which might more accurately be called a “starvation pyramid”—was partly designed by administrative diktat and partly ruled by the laws of the market. For Biebow, a non-Nazi who was in charge of public health, “the productivity of the ghetto had become an end in its own right, not the means to relieve the Reich of the cost of feeding Jews. [Events] would push this logic to a fatal turning point; those Jews who could not work ought not to be fed.” (p. 132) The Germans’ logic of deprivation was that, as the richer Jews became impoverished and faced hunger, they would hand over their hidden valuables for a meal.

Nazi propaganda had long portrayed the Jews as at simultaneously unclean and parasitically rich. The starvation pyramid of the overcrowded famine-stricken ghetto, where the scarcely-human-looking starving shared sidewalks with better-off neighbors still trying to make themselves dignified and presentable, provided images that could be deployed to support this. Everyone was being starved by the Nazis, but some were closer to the edge than others. Nazi propaganda narrated “the ghetto’s bad conditions [are] actually the rich Jews’ fault … there is a cruel hierarchy even amongst imprisoned Jews, and Jews have no sympathy or even basic awareness of their fellow Jews’ suffering.”

Some later commentaries suggest that the amateur photos taken by German soldiers were staged to dehumanize the starving and to place them in the same frame as the non-starving. Given that famine photography throughout the 20th century—whether in Russia, Bengal, Biafra, Ethiopia or Sudan—shows very similar images, and that in most cases the hungriest exist side-by-side with the well-fed, that’s unlikely. The truth is more chilling. The aim of Nazi hunger politics was material dehumanization, and the pictures reveal that this goal was accomplished. Starvation dehumanizes the individual. Famine breaks the bonds of compassion between people. And most crucially, as with every visual portrayal of starvation, the men responsible don’t appear in the pictures at all.

As Browning’s research has showed, the “ordinary men” involved in the Holocaust had a range of personal reactions and motives. What they shared was that they all considered Jews outside the moral community.

On September 19, 1941, Wehrmacht sergeant Heinrich Jöst decided to celebrate his birthday by touring the Warsaw ghetto with his camera. His photographs were private—he kept them for forty years before sharing them. They were not staged by Nazi propaganda apparatus, rather they were filtered by the worldview of a German army officer. Jöst’s choice of captions is telling—he is indifferent, treating human beings like wildlife in a game park. Consider this picture of a woman and her desperately sick child. Jöst’s caption reads: “Where would this rickshaw driver take this child who was obviously sick with Typhus? Was there still a hospital for Jews? No one among my German comrades could tell me.” Or this photograph, which he captioned: “Next to a lady with a good coat and shoes that had heels, stood next to this broken-down man, barefoot, with his barefoot child on his shoulders.”

In such portrayals we also sense a twisted circular logic: the visible degradation of the starving is justification for treating them as less than human. The image of a starving person evokes a visceral reaction of disgust, which is free-floating, and can be directed at the victim, not the perpetrator. The Nazis, having forced dehumanizing conditions of life on the Jews, then presented the scene of their crime as a fact of nature.

By contrast, most of the Jewish physicians’ pictures of the starving show them in the care of nurses, whose compassion and humanity are evident. It’s extraordinarily hard to make the starving look dignified, something over which humanitarian agencies and photojournalists have agonized in more recent times.

No Nazi official was prosecuted for starvation crimes in the Nuremberg trials. To the dismay of Lemkin, the crime of genocide was nowhere mentioned in the final judgement. In the High Command Trial of 1948, Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb was acquitted of enforcing the starvation siege of Leningrad, on the grounds that it was permissible under the laws of war. (In other areas, the Tribunal was ready to introduce new law retroactively, notably the concept of crimes against humanity.) In the Ministries’ Trial of 1947-49, Richard Walther Darré, Hitler’s Minister of Food and Agriculture, was prosecuted, but not for forced starvation under the Hungerplan (which was finalized by his deputy and successor, Herbert Bäcke, who committed suicide before he could be tried). In its judgment, the tribunal exonerated Darré of discrimination in providing rations to Jews on the grounds that the decrees imposing limited rations “were not in themselves so severe or their effects so harsh as to cause sickness or exposure to sickness or death.” (p. 384) The judges noted, however, this was the prelude to “more drastic cuts which finally led to the denial of foodstuffs necessary in life.” These were missed opportunities to declare “never again” for genocidal starvation.

In her article, Helen Fein includes other cases of ‘genocide by attrition’—the starvation policies of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and weaponized famine in Sudan. She concludes (p. 39) with an appeal to the international community and especially to health and aid professionals, to set up networks to prevent and punish genocide by attrition.