World War X began as the liberal peace sickened and died. That happened gradually, but the blow that in due course proved fatal was the 2008 financial crisis – and the US financial salvage operation that followed.

The funeral was held last week at the World Economic Forum in Davos. President Donald Trump launched his ‘Board of Peace’ – the peace-as-business model taken to a global scale. At Davos, the emphasis wasn’t on what the Board of Peace would do, but on sneering at the liberal multilateral system for its failures – failures that are of course largely attributable to Russia and the US itself.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney both praised and buried the universal rule-based order, saying that the world has moved from transition to rupture.

Here’s a shorter requiem for liberal peace. Following the end of the Cold War, liberalism – in both its economic and political variants – was victorious. What followed was two decades of a global liberal peace.

In the 1990s there were leftover conflicts from the Cold War, new wars that exploded in the unravelling of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, and a surge of conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa – but in all cases these were localized, contained, and everyone agreed on the basic formula for solving them – a combination of redesigned constitutional architecture along with an economic dividend for the populace.

The discussion around war and peace was practical, not philosophical. Peace was hyphenated – peace-making, peace-keeping, peace-building, regional peace and security. What made it work was the rising tide of an unprecedented worldwide economic boom.

The US went to war after the al-Qaeda attack of September 11, 2001. But the ‘Global War on Terror’ and the invasion of Iraq didn’t change the basic formula for peace. In fact, the Neo-cons were true believers that economic neo-liberalism plus democracy would bring peace.

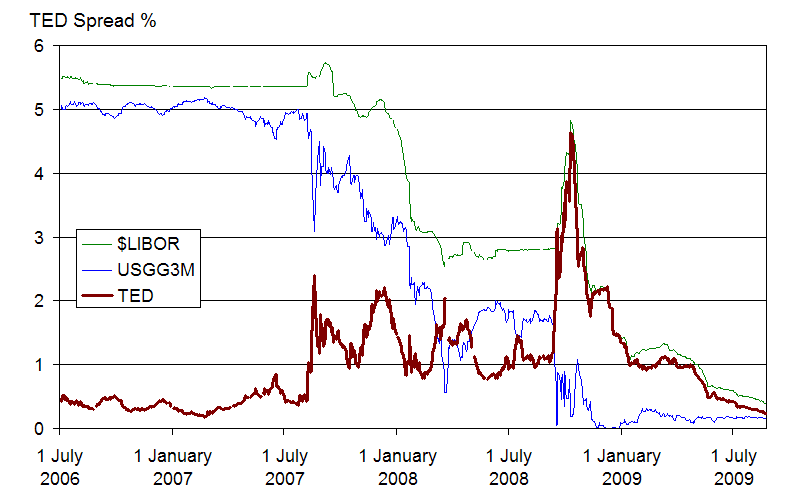

Several things foreshadowed the looming World War X. Most importantly, dark globalization was becoming enmeshed with political systems, driven by criminal money in Russia and elsewhere – and the US was itself liberally dispensing political payout to allies and clients in the War on Terror. Alongside this, Washington was weaponizing its control over financial transactions. As long as its targets were limited to terrorists and drug traffickers, the rest of the world wasn’t unhappy, but it soon became clear that targeted financial sanctions were an incredibly powerful weapon in the hands of one state alone, the US, and it wasn’t shy about using them.

The financial crash of 2008 and its aftermath changed everything. The US government rescued Wall Street, leaving the rest of the world to live with the realities of the harms inflicted by the distortion and mismanagement of the American economy and the fact that Washington’s response was to protect its own. It was an astonishing display of power.

That rescue package, and the even bigger one that was rolled out in response to Covid-19, fuelled the greatest technology boom – or bubble – of all time. And that in turn has fed tech moguls’ ambitions that literally surpass the human world.

The crash and its aftermath put in place two further causes of World War X.

First, public finance in poor, fragile countries became more and more constrained. The immediate impact wasn’t so bad – there was cheap money and the commodities boom continued. But Washington’s financial institutions – the US Federal Reserve, the US Treasury, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – refused to accommodate the needs of poor countries. As the commodities boom petered out and as returns to US domestic stocks soared, FDI and ODA were squeezed. The public revenues needed to sustain peace settlements were squeezed.

The kleptocratic backroom deals had been the peacemakers’ dirty secret. Now they became the essential ingredient for success, or failure.

Politicians need to survive no matter what. If they can’t deliver public goods such as welfare and development, they focus instead on managing the political marketplace. That means corruption in one form or another. Weak public revenues plus corruption doomed popular uprisings. Governments and rebels became more reliant on foreign patrons, helping make civil wars metastasize into intractable regional conflict systems. War economies of plunder and deprivation became more entrenched and after decades in which they almost disappeared, famines returned.

The second impact of the crash was that many middle powers realized that they needed to escape from – or at least loosen – the shackles of the US dollar system. Russia, Iran and a few countries other countries were already fearful of targeted sanctions and wanted to attack the dollar. Large developing countries were worried that they had forfeited financial sovereignty. And China, the emerging industrial superpower, worried about its financial vulnerabilities.

The signal event here was the formation of the BRICS – the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa club – in 2009. Each had its own reasons for wanting to challenge the US dollar; each wanted the authority to make its own money. The US had the choice of whether to acknowledge its challengers’ concerns and re-engineer the global financial system for the collective good, or to carry on as though its exorbitant privilege were an entitlement. It chose the second path. Washington was confident it could beat off the challengers, and so far it has been proven right. But there has been an awful lot of collateral damage from that decision.

World War X began when existing conflicts metastasized into a global, interconnected system. That happened with parallel events in the early 2010s – the NATO intervention in Libya and that country’s descent into civil war, the war in Syria and the international escalation of Russian influence operations when Vladimir Putin returned to Russia’s presidency in 2012. By the time Trump began his first term, vast regions of the world were run as political marketplaces.

The squeeze on public finance and the rise of transnational loyalty payments caught peacemakers in a trap. Peace agreements looked less and less like democratic constitutional settlements and more and more like cynical bargains over power and money.

But even the most hard-bitten political business operators prefer to have some ideological cover – ethno-nationalism and religion are classic places to look for this. They readily veer into the old fascist justification of sovereign power as the true representation of national identity and popular will. Today there are new forms of plutocratic populism and even bizarre eschatologies spawned by the transhuman ambitions of tech billionaires.

All these ideologies bloomed as World War X matured – they’re its corollary, not its cause.

The Board of Peace makes the underlying geo-kleptocracy absolutely clear. Peace will now be pay-to-play dealmaking, with everything including sovereignty for sale at a price or seizure if the price isn’t right. Trump’s vision of world peace is a world run by, and for, imperial political-business CEOs – above all, Trump himself.