The ongoing war in Yemen is the source of one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in the world today, with millions of Yemenis facing an imminent threat of famine, in addition to the 10,000 (as of January 2017) who have been directly killed by the fighting. All sides have committed major abuses of international humanitarian law, including indiscriminate attacks against civilians and civilian infrastructure. The war seems to be at a stalemate, and is becoming even more complex with recent fighting in Aden between UAE-backed southern separatists, and formerly-allied Saudi-backed forces loyal to the internationally-recognized ‘government’ (if Yemen can be said to possess such a thing) of exiled President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi.

The US and UK have rightly drawn opprobrium as the primary arms suppliers of Saudi Arabia, the leader of the pro-Hadi coalition in Yemen, pursuing its war against the Houthi rebels and their allies among the Yemeni army, who are in control of the capital Sana’a. However, the coalition includes several other countries that are playing major roles, and this coalition between them has a diversity of arms suppliers.

The Houthis and their allies

On one side of the war, the Houthis in control of Sana’a and much of the north and west of Yemen, there is increasing evidence that Iran is indeed supplying them with arms, in violation of a UN embargo on the group and their allies. The most recent report by the UN Panel of Experts for Yemen, in January 2018, pointed in particular to missiles and UAVs used by the Houthis bearing strong similarity to those produced by Iran. The report does not point to any other state as a supplier.

The Houthis were, until November 2017, allied with forces loyal to the former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. The rupture of this alliance led to several days of fighting in Sana’a, culminating with the killing of Saleh by the Houthis on 4th December. Since then, according to the UN report, the Houthis have successfully either crushed or co-opted the remainder of the Saleh-loyalist forces.

Also supporting the Houthis are numerous units of the former Yemeni army that took the Houthi-Saleh side when they captured Sana’a in 2014. Thus, the Houthis were able to capture large quantities of arms from Yemeni army stockpiles, accounting for a large proportion of their arms supplies.

The Saudi-led coalition

On the ‘other side’ – though it can barely be considered a single side, except in its opposition to the Houthis – Saudi Arabia leads a coalition of outside states that are intervening militarily in Yemen, nominally in support of the internationally-recognized government of President Hadi; although many of the Yemeni forces supported by the coalition owe little or no loyalty to the Hadi government.[1] As well as elements of the Yemeni armed forces that continue to support Hadi are a variety of tribal militias armed, trained and funded by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; various foreign mercenaries; and forces loyal to the Southern Transitional Council, supported by the UAE, who seek an independent South Yemen and who recently fought with pro-Hadi forces in the coastal city of Aden.

Saudi Arabia leads the coalition, and appears to conduct the majority of the air strikes, and lead the naval blockade of Yemen that is a major factor in the growing humanitarian catastrophe. However, Saudi Arabia does not have a significant presence of ground troops in Yemen, although some are present in Aden. The Saudi government stated at the beginning of the campaign in March 2015 that they were deploying 100 warplanes to the conflict, but more recent figures for the number of men, warplanes and naval vessels committed are not readily available.

The United Arab Emirates also participates in the air war, and plays a key role on the ground in southern Yemen, in the fight against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) as well as against the Houthis. While this is mostly conducted through Yemeni forces they sponsor, arm and train, the growing Emirati military footprint in Yemen has led to a growing local perception of the UAE as a colonizing force. UAE-established detention centers in southern Yemen have been severely criticized for human rights abuses, including arbitrary detention and torture. The UAE committed 30 warplanes to the coalition effort in March 2015.

Sudan has the largest presence of ground troops of any external member of the coalition. Some sources estimate a presence of around 8,000 Sudanese troops in Yemen. The forces deployed are from the elite counter-insurgency Rapid Support Forces (RSF), that have been accused of systematic human rights abuses in numerous counter-insurgency campaigns in Sudan. The RSF includes elements from the notorious Janjaweed militia, notorious for its role in atrocities in Darfur. Sudan has received $2.6 billion from Saudi Arabia for its role in Yemen, and appears to be using the Yemen conflict to move away from Iran and towards the Gulf states, and to improve relations with the US government, which in October 2017 lifted a range of sanctions on Sudan in place since 1997, and which is reviewing Sudan’s status on the US list of ‘state sponsors of terrorism’.

Egypt sent four warships to support the Saudi naval blockade of Yemen at the beginning of the intervention in March 2015. They also participate in the air campaign (with 4 planes initially), and sent 800 ground troops to Yemen in September 2015.

Morocco pledged 1,500 ground troops to the Yemen war in December 2015. They also participate in the air campaign, committing 6 planes initially. One Moroccan F-16 crashed or was shot down in 2015.

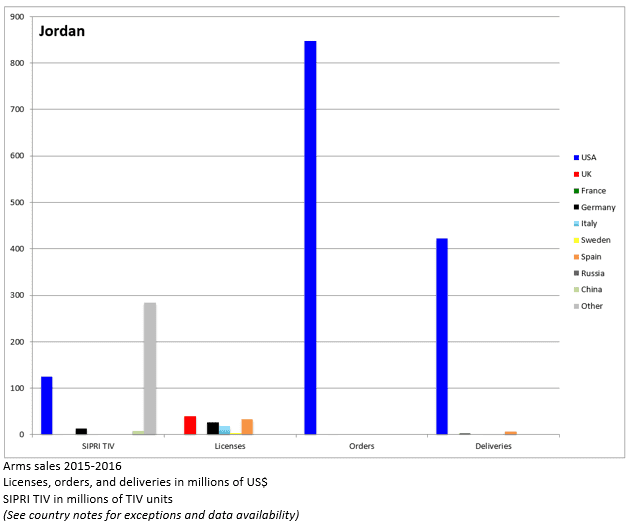

Also participating in the air war are Bahrain and Kuwait (15 planes each), and Jordan (6). Qatar participated in the coalition until June 2017 when they withdrew following the breakdown in relations with Saudi Arabia and UAE. Bahrain and Jordan have also had planes crash in Yemen, confirming their participation.

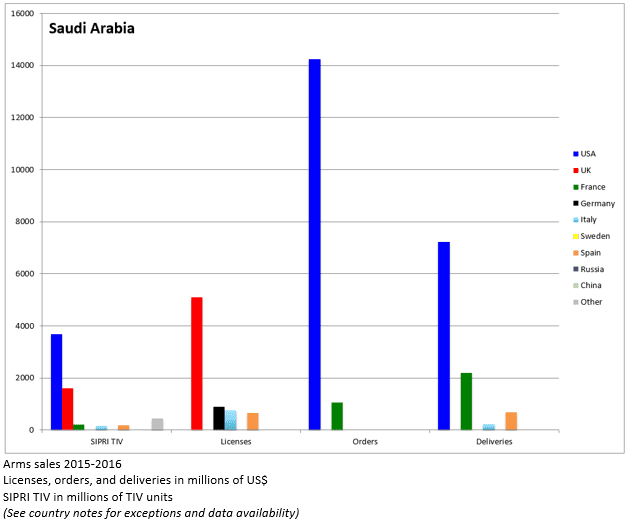

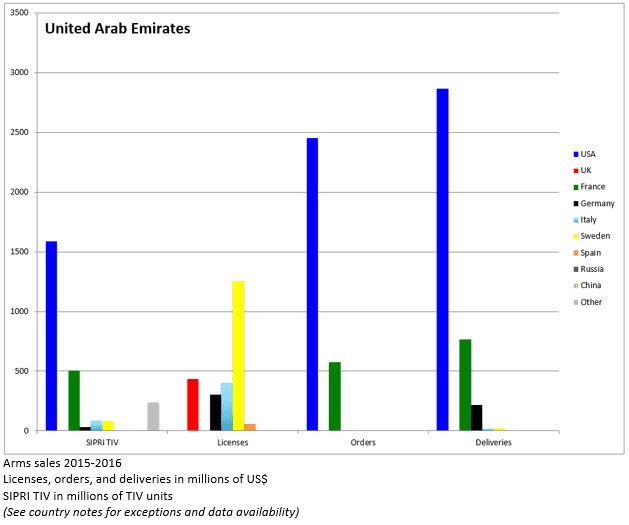

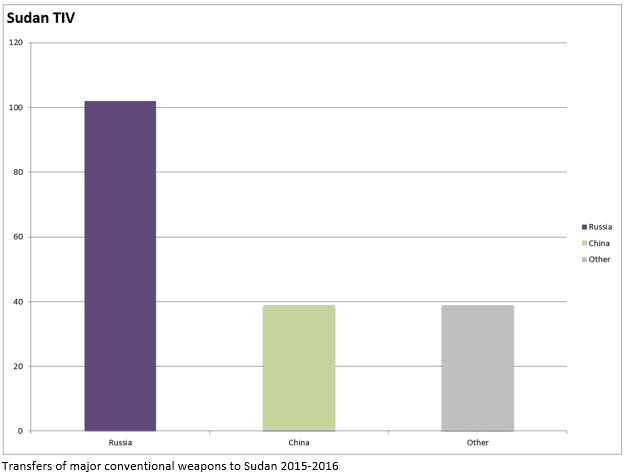

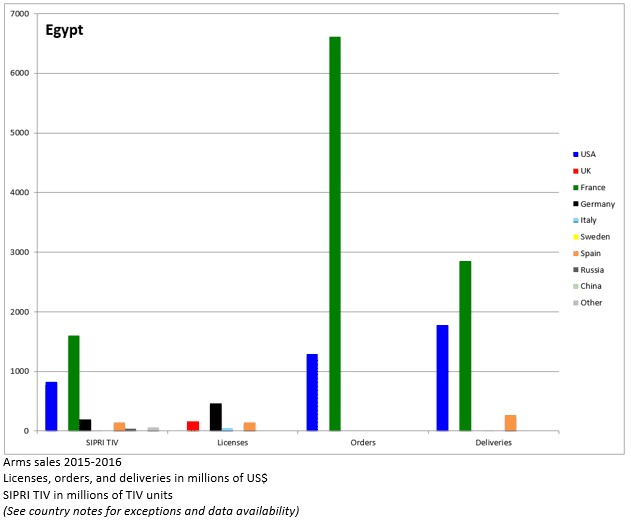

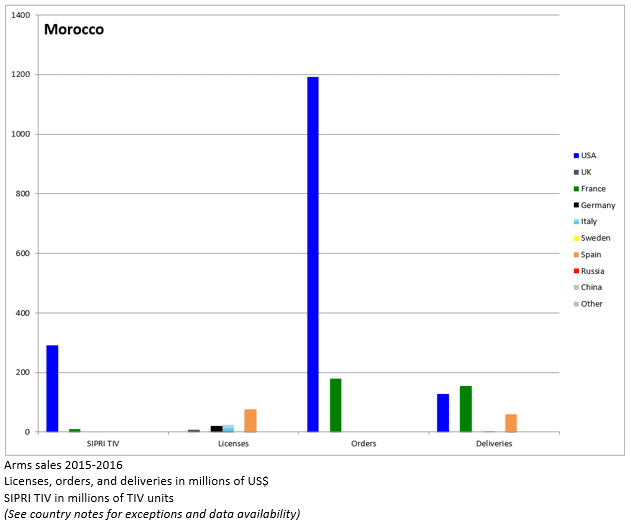

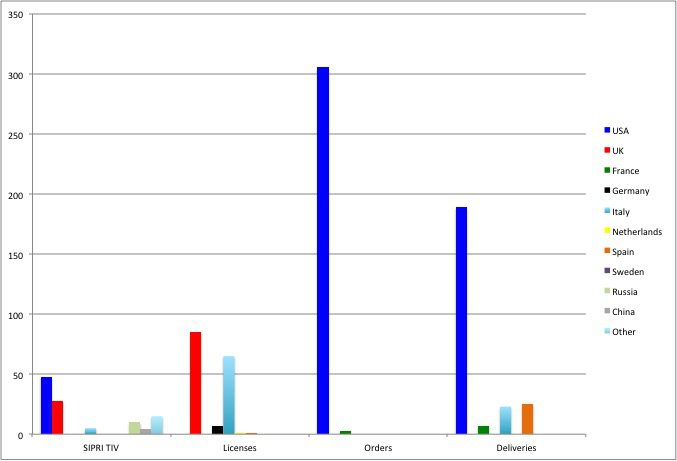

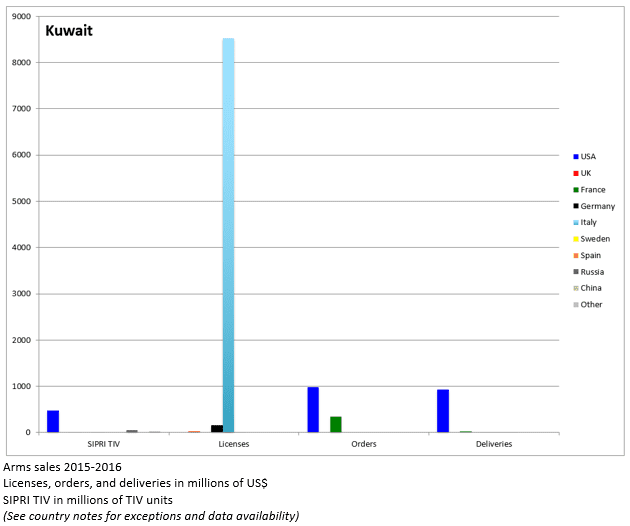

So who are arming these countries? Table 1 below gives data on the supply of arms to each of the coalition members by the US, the top 6 EU arms producers, Russia, and China, using several different measures, where available: financial measures of deliveries, contracts or orders, and export licenses;[2] and SIPRI’s Trend Indicator Value (TIV) measure of the volume of major conventional weapons transfers. The latter is the only measure that is available for all exporters. The data is for 2015-2016 in most cases.

Lic: Value of individual export licenses granted for arms sales 2015-2016, US$ million (a zero indicates a figure of less than $0.5 million)

Ord: Value of orders for arms 2015-2016, US$ millions (a zero indicates a figure of less than $0.5 million)

Del: Value of delivery of arms 2015-2016, US$ millions (a zero indicates a figure of less than $0.5 million)

TIV: SIPRI Trend Indicator Value of deliveries of major conventional weapons 2015-2016, millions. (See here for definition). A zero indicates that there were no major conventional

weapons deliveries during 2015-2016.

Country Notes

USA: The US provides export license data for Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), but it is not possible to distinguish licenses for exports to foreign governments, and exports to US forces and government agencies operating in the destination country. Figures for deliveries include both sales through government-government Foreign Military Sales (FMS) agreements, and through DCS agreements. Figures for orders are for FMS only.

UK: The UK does not provide any information on the value of arms delivered, and provides figures for orders only on a regional basis. UK export license figures do not include ‘open’ licenses that allow for multiple shipments to one or more destinations, and which account for a large proportion of UK exports.

France has recently changed their export licensing system from a multiple license system at the point of negotiation, agreement, and delivery, to a single license system incorporating all three. The available license figures therefore cover all licenses for negotiations, most of which will never turn into deliveries. The very high magnitude of the figures, in the hundreds of billions of euros, are therefore essentially useless as a measurement tool.

Germany does not provide data on the value of arms delivered, except for the subcategory of “weapons of war”, for which a total figure is given, along with the total exported to EU and NATO countries, and the amount exported to the top 3 other recipients, which in 2015 and 2016 did not include any of the countries considered here. Figures for orders are not available.

Italy: Figures for the dollar value of deliveries are for 2015 only. Figures for orders are not available.

Spain: Figures for the dollar value of both orders and deliveries are for 2015 and the first half of 2016 only. Figures for orders are not available.

Russia does not provide any country-by-country data on its arms exports, so the only information available is from SIPRI, which collects its data independently.

China does not provide any data on its arms exports, so the only information available is from SIPRI, which collects its data independently.

Others includes countries with a variety of reporting practices, so that totals cannot be produced except for the SIPRI TIV, for which data is collected by SIPRI for all countries.

The multiple measures are valuable, as not all are available for all countries, and as they measure different aspects of arms transfers and arms transfer policy. Figures for deliveries (both SIPRI and financial value) measure recent transfers, while those for licenses and orders are an indication of current or future transfers, and of recent decision-making. The SIPRI figures are available for all countries, but they only cover major conventional weapons, and therefore miss aspects of the arms trade between each pair of countries, as well as not providing a financial measure.

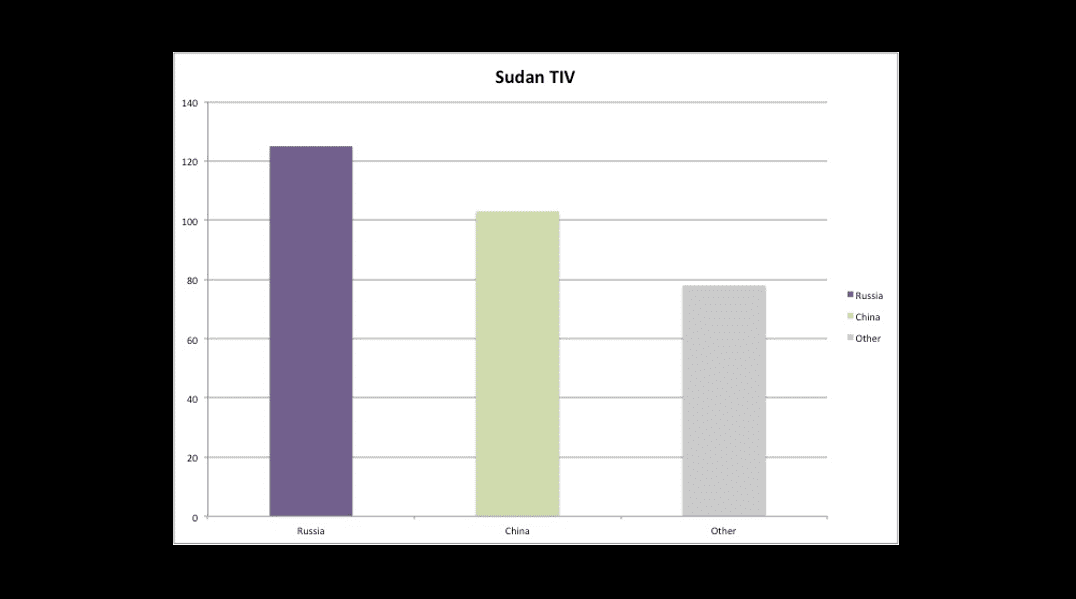

The table shows that all these countries are significant arms suppliers to the Saudi-led coalition. Sudan is the subject of arms embargoes by the EU and the US, in spite of the lifting of other sanctions by the latter, and thus receives the bulk of its limited major arms supplies from Russia and China. Russia supplied Sudan with combat and transport helicopters in 2015-16, from deals signed in 2013, but has not signed any new contracts for major weapons since then. China has supplied a variety of land systems and surface-to-air missiles, and agreed the sale of 6 FTC-2000 trainer/combat aircraft to Sudan in 2015.[3]

The USA, unsurprisingly, is either the largest or second largest supplier to all of these countries, although Bahrain’s arms purchases are fairly limited. All of the EU exporters are significant suppliers to one or more of the other members of the coalition.

The UK is the second largest supplier to Saudi Arabia, who are the UK’s largest customer by far. British Tornado and Typhoon aircraft are a major component of the Saudi Air Force, active in Yemen.The UK has also licensed significant quantities of arms to Egypt.

France is the biggest supplier of arms to Egypt, with $2.8 billion-worth delivered in 2015-16, including a frigate, 2 Mistral helicopter carriers, and 24 Rafale combat aircraft. France is also a major supplier to Saudi Arabia, with deliveries of over 2 billion dollars including armored vehicles, air defense systems, and aircraft subsystems; and also has significant orders and/or deliveries to Kuwait, Morocco (another small-scale buyer, to whom France had the largest financial value of deliveries), and the UAE.

Germany plays a lesser role, but has made significant deliveries (based on SIPRI data) to Egypt (armored vehicles and submarines), and has licensed significant quantities of military equipment to Saudi Arabia (including naval patrol craft), Egypt, the UAE, and Kuwait.

Italy agreed a deal in 2016 to sell 28 Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft to Kuwait for EUR7.8 billion, accounting for the export license figure quoted. They also make significant supplies to Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Sweden’s large license to the UAE comes from a $1.3 billion deal in 2016 for two Erieye Airborne Early Warning and Control systems, which could potentially play a significant role in an air campaign.

Spain joins most of the others on the Saudi bandwagon, as well as being a significant supplier to Egypt and (relatively speaking) Morocco. Spain’s major arms supplies to Egypt and Saudi consist of transport aircraft.

We may note that all of the Western exporters except Sweden are significant arms suppliers to Saudi Arabia, while all but Germany and Spain are significant suppliers to the UAE. Jordan is the only coalition member whose primary supplier—The Netherlands—is not included in the table. The country also receives a significant proportion of its arms from Israel and the UAE. The US, UK, France, and Italy have all licensed and/or delivered combat aircraft to members of the coalition, while Sweden has supplied important aerial subsystems and Germany has supplied naval vessels, potentially relevant to the blockade.

Debates over arms sales

Arms exports to Saudi Arabia in particular are highly controversial in many of the exporter countries, due both to the Kingdom’s egregious human rights record, and their role as the leading external combatant in the Yemen war, responsible for numerous violations of international humanitarian war and the crippling, famine-inducing blockade. Supplies to other countries in the coalition are also controversial in some cases (sales to Egypt in particular due to the brutal nature of the current regime), but in some cases pass ‘under the radar’ due to their lesser role in the war.

The EU Parliament passed a non-binding resolution calling for an arms embargo on Saudi Arabia in February 2016, a call that they renewed in an overwhelming vote in November 2017. To date, however, only one EU member state has taken up this call, with the Netherlands Parliament voting for an arms embargo in March 2016. They may be followed by Germany, however, as the coalition agreement between Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democrats (SDU) calls for an end to arms sales to countries involved in the Yemen war. While the agreement still needs to be ratified by a vote of the SDU, the German government announced on January 20th that it would cease all exports to countries involved in the war. However, it was unclear if this applied only to new export licenses, or also to exports previously licensed but not yet delivered.

The United States has long been the leading supplier of arms to Saudi Arabia, which it sees as a key ally and force for stability in the Gulf region. Major arms sales have been a regular practice of administrations of all colors, although objections from the Israeli lobby stopped some major sales in the 1980s; something which is no longer an issue given the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel in recent decades. The Obama administration was no exception, but did, in response to concerns over the indiscriminate use of US weapons in Yemen, suspended the planned export of certain precision-guided munitions. The overturning of this suspension by President Trump in 2017 led to a rare vote in Congress to attempt to block the sale. The attempt was defeated in the Senate by 53 votes to 47, but such a high vote against an arms sale—including some Republicans as well as most Democrats—was highly unusual. In general, US arms sales to Saudi Arabia have enjoyed broad bipartisan support, and indeed there has been much less Congressional opposition to the bulk of US arms sales to the Kingdom (although there is considerable opposition in civil society).

The Obama Administration also froze some military aid and arms sales to Egypt in 2013, following the military coup, but restored this in March 2015—shortly after the start of the Yemen war—citing the need to combat the Islamic State. The Yemen war does not appear to have been a consideration in US arms sales decisions to Egypt or other members of the coalition.

The UK’s arms sales to Saudi Arabia are a mainstay of the UK arms industry, and have, like in the US, generally enjoyed strong bipartisan support, in spite of considerable civil society and media controversy, and some political opposition from the left. Nowhere is this absolute government commitment to maintaining arms sales to Saudi more evident than in the cancellation of the Serious Fraud Office investigation into the Al Yamamah arms sales in 2006. The Saudi role in Yemen led to a legal challenge by Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) in 2016 against UK arms sales to the country, on the grounds that they violated the UK’s own export licensing criteria, which forbid the sale of arms that might be used to commit violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). CAAT were granted permission to seek judicial review, but the UK High Court found in favor of the government in July 2017, although the case is now under appeal.

The bipartisan support for arms sales to Saudi Arabia has, however, ended, with the opposition Labour Party under leader Jeremy Corbyn taking a stance against such sales. The Labour Party manifesto for the 2017 general election pledged to suspend arms sales to parties to the Yemen conflict until an independent UN investigation has been conducted into alleged violations of IHL in Yemen. Were Labour to attain power, however, such a commitment would undoubtedly face major pushback from the foreign policy and defense establishment, the arms industry, and some trade unions with members in the industry.

The arms trade is highly controversial also in Sweden. Following many years of debate and a Parliamentary investigation, on 28 February 2018 the Swedish Parliament passed a new stricter set of export control criteria—almost certain to pass given the measure’s bipartisan support—including a so-called ‘democracy criterion’, which would mean that a state’s democratic status or otherwise would be a major factor in evaluating potential arms sales, rather than just the likely use of the equipment to be exported. However, this would not involve a complete ban on arms exports to non-democracies. Sweden’s arms exports to Saudi Arabia are very small, but non-zero, and it is likely that these very limited sale would be an easy early target of the new regulations. However, the government’s plans to introduce the new rules, nor its concerns regarding the Yemen war, have not prevented its support for significant ongoing arms sales to the UAE, in particular the Erieye system mentioned above. Moreover, Saab, the producer of Erieye, clearly expect an ongoing relationship with UAE, having opened a development and production center in the Emirates in December 2017. In theory the new rules might lead to stronger questioning of sales to UAE and the other members of the coalition—all clearly non-democracies—but the prospect of losing such a lucrative customer might continue to override democratic and other concerns.

The arms trade in France periodically becomes the subject of controversy in the wake of specific corruption scandals. In general, like in other countries, parties of left and right have been broadly supportive of French arms sales efforts. However, the Yemen war has led to an increasing level of criticism of French arms sales to Egypt and Saudi Arabia, from sections of the media and from civil society organizations, such as Amnesty International and SumOfUs. This pressure, as well as the call for an arms embargo against Saudi Arabia from the European Parliament, appears to have gained some traction, leading to reported disagreements within the current government: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has apparently opposed certain proposed arms sales, although the Ministry of Defense has supported them, the latter ultimately receiving support from the Presidency and the Prime Minister. None of the major candidates in the 2017 Presidential election expressed opposition to France’s continuing arms trade with Saudi Arabia and other members of the Yemen coalition.

The author welcomes any commentary on the state of debate in Spain and Italy, on which I admit severe limitations to my knowledge. [Edit: but see the interesting comment by Edoardo Lai regarding Italy below.]

Conclusion

All major arms exporters are suppliers to at least some of the participants in the Yemen conflict, and the horrific consequences of the war have, up to now, done little to dent the enthusiasm of the US and European exporters to sell to the lucrative Gulf arms market. Saudi Arabia, in particular, the world’s 4th largest military spender, is almost entirely dependent on imported arms, which most Western producers have been very happy to supply. However, the Yemen war has certainly led to a significant heightening of debate on arms sales, reaching in some cases the level of serious legislative opposition, and breaking what has often been a cross-party consensus in favor of arms sales in some countries. The Netherlands has been the first significant European country to ban arms sales to Saudi Arabia, although as one Dutch journalist pointed out at the time, this is not very meaningful as the Netherlands sold practically nothing to Saudi Arabia in any case. Somewhat more significant is the decision by the German government to end arms sales to all countries involved in the war, in keeping with the new coalition agreement. Nonetheless, Germany is not one of the biggest sellers to these countries, and for the big three western suppliers: the USA, the UK, and France: there is no sign yet of a change in policy—though political dissent is growing.

[1] See report of UN Panel of Experts for Yemen, January 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/letter-dated-26-january-2018-panel-experts-yemen-mandated-security-council-resolution

[2] These data come from countries’ national reports on arms exports, which can be found in SIPRI’s database of national export reports, except for data on UK export licenses, which come from the Campaign Against Arms Trade database, which presents UK licensing data in a user-friendly format.

[3] All information on specific arms deals is from the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers