A nuclear strike almost certainly qualifies as an act of genocide. Does a threat of nuclear attack constitute incitement to genocide?

This question is not new, but newly invigorated by today’s crises. In 2005, then-Iranian President Ahmadinejad generated great fervor stated, in a contested translation, that Iran would “wipe Israel off the map.” In some circles, the phrase prompted an effort to impose punitive measures based on claims of incitement to genocide and became casus belli for those who wanted to pre-emptively attack Iran. The Obama-era nuclear agreement eventually cooled these tensions; though Pres. Trump is now backing away from it (although his own defense secretary continues to support it).

The 2005 Ahmadinejad statement finds a concerning parallel with the US-North Korea standoff … although it is not entirely clear to me how one might cast the roles in this (albeit limited) parallel example. The U.S. President threatened “fire and fury” against North Korea, and Kim Jong-un has a record of missile provocations. But do these examples, or that of Ahmadinejad, rise to the level of incitement?

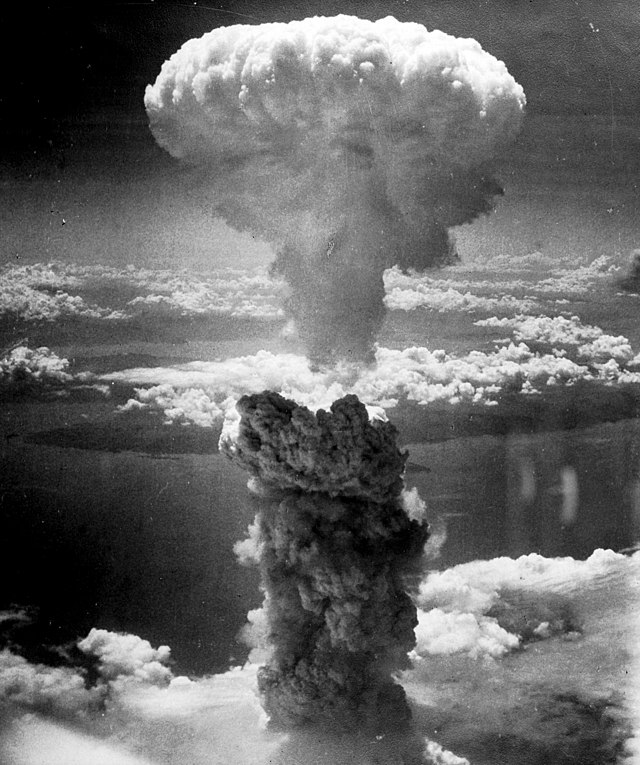

A generation ago, some genocide scholars contemplated the continuities between genocide and nuclear conflict. Among them were Robert Jay Lifton and Eric Markusen, who wrote in 1990 that the two phenomenon shared a continuity in destructive logic:

“a genocidal system is not a matter of a particular weapons structure or strategic concept so much as an overall constellation of men, weapons, and war-fighting plans which, if implemented, could end human civilization in minutes and the greater part of human life on the planet within days or even hours.”

(The Genocidal Mentality: Nazi Holocaust and Nuclear Threat, 3)

Thus they argued, and I think convincingly, that given the destructiveness of nuclear weapons and their long-term impact on even surviving populations, that the weapon has an inherently genocidal logic. They were describing the capacities developed by the US and USSR, but the analysis holds even for more limited attacks. A nuclear attack includes an intent to destroy, at least “in part” (and undoubtedly it would be a “significant part” of the legal threshold established in the ICTY’s Srebrenica decisions), a group—although possibly defined geographically rather than by nation, ethnicity, religious or race, as such.

But is it helpful to name inflammatory rhetoric as genocidal incitement? I have in the past been wary of this move, seeing behind it an agenda for escalating hostilities that would likely cause enormous civilian suffering, rather than increasing the urgency with which diplomatic solutions are sought. Could “genocide” or “responsibility to protect” provide a framework for focusing non-violent responses? It has not generally served this purpose, but it might be able to.

Unfortunately, there is a more ominous implication of today’s nuclear threats for the atrocities prevention and response agenda. The crises bear further evidence that the international environment in which the agenda was able to take on concrete policy forms is today dissipating.

Even within the dry recaps of UN debates, the dissipation is noticeable. The recent UN Secretary-General’s ninth annual report on RtoP located today’s dilemma as the widening “gap between our stated commitment to the responsibility to protect and the daily reality confronted by populations exposed to the risk of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity,” which is certainly true. The report diplomatically sticks to the agenda established in the early 2000s: establishing greater accountability, furthering civil society engagement on prevention and response, increasing the willingness and capacity of regional organizations, and balancing between prevention and response (always bemoaning the limited attention for prevention). Nonetheless, dissatisfaction with the rode played by the UNSC and its member states is clear. Overall, as, the Stanley Foundation, the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung recently noted in a Policy Memo, across the UN system, the conversation about RtoP is increasingly polarized—any consensus that may have existed, has vanished.

However much one might explain away today’s threats of nuclear war tossed around by a UNSC member as rhetorical escalation unrelated to policy, willingness to play with such scale of destruction exposes a fundamental problem for any efforts to prevent and respond to atrocities. The work of preserving civilian protection as a guiding light for international action – no matter that it was never realized – now must understood as tending the embers of a very weak flame.

The nuclear threat is not only a threat of atrocities, but it is also a threat on the very efforts to prioritize atrocity prevention and response.