In this conversation with Marc Burrows, we probed the practices and value of harm reduction policies. For me, as is the case for families and communities across the country, the issue is profoundly personal. Below I explain why and introduce some background, before turning to the conversation with Marc.

On August 10, 2022, my brother, Matthew, nearly succumbed to a fatal fentanyl overdose.

I was getting ready for bed with my partner when I received a message from a woman on Facebook. It said, “I need you to call me as soon as you get this. It’s about Matt, and it’s not good.” When I called her, she told me that my brother had died from an overdose. I remember grabbing fistfuls of my partner’s comforter as adrenaline spread throughout my body. My brain was registering overwhelming trauma and preparing itself for survival mode. I began swaying back and forth; a movement I had seen at many synagogues as my Jewish loved ones prayed. I let out a scream that came from the deepest part of me: the part that had spent decades grieving my brother’s death before I even received this call.

I made 46 phone calls that night. First to my mother, her partner, his daughter, my best friend—no answer—then to the hotel where my brother was found, the police, the hospitals. In between calls, I heaved and screamed out for my brother. It had been three hours since the woman who contacted me found him unresponsive, and I still couldn’t find where the ambulance had taken him. My body, in a state of complete shock, began to instinctively rock back and forth as a means of self-soothing. I remember thinking, “It’s happening. I am losing my brother. It’s happening. No. No. Please. No.”

I had a contingency plan in place: in the event of an emergency involving one of my brothers, I would be taken to my best friend, who would know how to assist. My partner took me to her house, where I found myself on the verge of a panic attack on the driveway. Surrounded by my loved ones, we continued our search for my brother. Eventually, a receptionist at a nearby hospital advised me to contact Emergency Medical Services (EMS), as they maintain records of all their calls. When I spoke with an EMS representative, he provided me with the contact information for the emergency room where my brother had been taken. However, he was unable to confirm my brother’s condition.

As I called the hospital, I braced myself. A woman answered the phone, put me on hold, and when she got back on the line, she asked, “Do you want to talk to him through me or directly?”

“He’s alive?” I asked. When she confirmed that he was, I repeated my question. Someone, I assume emergency medical responders, administered naloxone, a medication that swiftly reverses opioid overdoses, typically caused by heroin, fentanyl, and prescription opioid medications. My brother’s life had been saved, at least for now.

I am far from alone in fearing and then receiving a call that a loved one had overdosed. A recent report by the RAND Corporation reveals that over 40 percent of Americans know someone who has died of a drug overdose, and approximately one-third of them report that their lives were impacted by the death. It’s not solely the loss of a precious life; the ramifications of overdose fatalities ripple through communities.

Not long after Matthew’s overdose, he was incarcerated due to drug-related offenses. In my youth, before I embraced prison abolitionism, I used to find solace in his incarceration, mistakenly thinking prisons would keep him safe from drugs. However, the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (from 2019) reveal that the number of individuals who have died from drug or alcohol intoxication while in state prisons increased by more than 600% from 2001 to 2018. This grim reality underscores the United States’ penchant for punitive responses rather than addressing what is undeniably a public health crisis.

How can we address this public health crisis effectively, especially when the US response seems limited to either incarcerating our loved ones or facilitating fatal outcomes?

The solutions might challenge commonly accepted beliefs. I consulted Marc Burrows, the Founder and Executive Director of Challenges INC SC in Powdersville, South Carolina. Challenges Inc. seeks to “reduce the damage caused by the War on Drugs so that people who use drugs can live safe, healthy lives in our community.”

A Brief History on US Drug War Policies

The War on Drugs has spanned decades, evolving through various forms and misappropriations of funds. US Presidents have consistently perpetuated this war, at the expense of Black, brown, and poor communities both domestically and internationally. Most researchers mark the beginning with Nixon’s Controlled Substances Act in 1970, which expanded federal drug control agencies, established the Drug Enforcement Administration, and implemented mandatory sentencing and no-knock warrants.

Reagan intensified this approach by advocating for the incarceration of individuals involved in nonviolent drug offenses. President Bill Clinton, elected on a ‘tough on crime’ platform, further escalated the war on drugs with the 1994 Crime Bill. This $30 billion legislation funded 125,000 new state prison cells, mandated life sentences through three-strikes laws, and added 60 new crimes eligible for the death penalty. Between 1980 and 1997, the number of people imprisoned for nonviolent, drug-related crimes rose from 50,000 to 400,000.

President Bush resisted efforts to reduce the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine and declined to prohibit funding for syringe access programs. The allocation of funds under President Obama mirrored that of his predecessors, Bush and Clinton, with the majority directed toward enforcing anti-drug laws, including measures to curtail the flow of drugs across the US-Mexico border and supporting the eradication of drug crops in Latin America and Asia. More recently, President Trump advocated for harsher drug sentences, including the imposition of the death penalty for drug traffickers, smugglers, and dealers.

Before his presidency, Biden supported the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. As President, he pardoned some federal marijuana offenses, but this action did not lead to the release of any incarcerated individuals and came only after activists criticized his contradictory statements regarding Brittney Griner, who was arrested in Russia for less than a gram of cannabis oil.

The historical trajectory of the War on Drugs reveals a pattern of escalating punitive measures rather than focusing on rehabilitation or addressing the root causes of drug-related issues. The legacy of these policies underscores the urgent need for comprehensive and equitable approaches to drugs that genuinely prioritizes justice and individual and community well-being.

Addressing the Gap: How is Harm Reduction Differ?

According to the National Harm Reduction Coalition, harm reduction has its origins and inspiration in several movements and strategies that emerged across the US during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. These include the Black Panther Party’s survival programs, such as the free breakfast program; the Young Lords’ implementation of an acupuncture program for heroin users; feminist activists’ efforts in the women’s health movement of the 1970s; and grassroots responses to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and beyond.

According to the Florida Harm Reduction Collective (FLHRC), “Harm reduction is a set of strategies that help to reduce or eliminate the harms associated with substance use. This includes efforts ranging anywhere from building relations with individuals who are unhoused and/or use drugs, to pushing towards ending the War on Drugs.” At its heart, harm reduction emphasizes including and elevating the voices and experiences of individuals who use or have used drugs. This approach prioritizes life-sustaining strategies over imposing abstinence.

Challenges Inc SC states that, “participants of a program like ours are 5x more likely to enter into treatment and 3x more likely to stop using drugs than those who are not. These prevention services also decrease the spread of diseases like HIV and Hep C by up to 80%.”

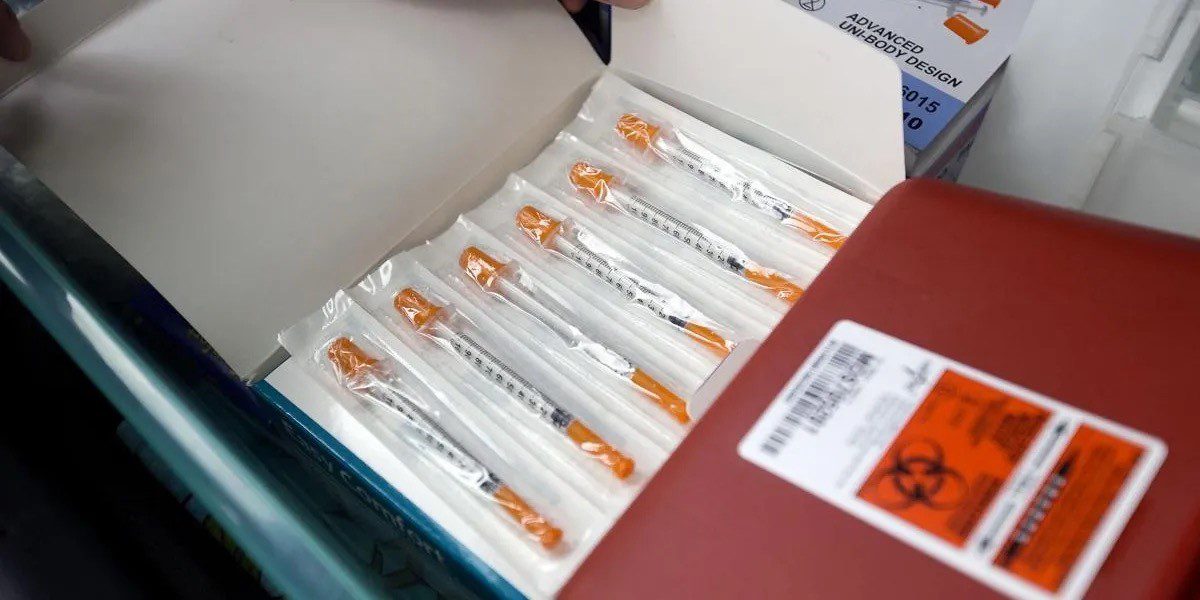

I spoke with harm reduction expert, Marc Burrows, about the practices and policies around harm reduction. Marc Burrows, MSW, LMSW, CPSS, is an addiction professional in upstate South Carolina specializing in the field of harm reduction and drug user health. I initially met Marc in 2019 through my loved ones, Shenita and Margie. However, it was in 2024 that Marc truly became an invaluable friend to our family. Understanding my brother’s limitations for standing work, Marc provided him with a meaningful role assembling naloxone kits, which allowed my brother to take pride in his contributions for the first time. In addition to this work, Marc offered crucial services and support to my brother. Although I was previously aware of the importance of harm reduction, this firsthand experience has profoundly challenged my perspectives on how we address substance use.

B. Arneson: Why are abstinence-only programs problematic?

Marc Burrows: So, depending on how long the program is willing to tolerate it—let’s say a month or two months—eventually, either the patient or the program will reach a breaking point. One side will say, ‘I can’t comply with this anymore, I’m not showing up,’ or the program will say, ‘We’re not putting up with this any longer; you’re out.’ It’s a lose-lose situation.

On the other hand, if the program decides to continue working with the person, the worst-case scenario is that the individual might still be engaging in drug use, but at least they remain engaged with the treatment professional and in treatment. This approach seems like a no-brainer.

The addiction treatment industry often clings to outdated and punitive practices. Much of what is done lacks evidence-based support. There is no solid research proving that attending a certain number of counseling appointments or undergoing urine drug screenings directly leads to better outcomes, such as reduced substance use. These practices often serve more to monitor and protect the treatment program from liability rather than to genuinely support the individual. The industry’s reliance on punitive measures and rigid requirements, rather than focusing on truly helping people, is a significant issue.

We’re setting unrealistic expectations that the person cannot meet and that don’t even benefit them. When we discharge the person, things often get worse. Essentially, that summarizes the issue with treatment.

B. Arneson: It’s clear that you have an understanding of how these programs work in reality. I have had a similar experience with Matthew. When did you first recognize the significant gap in existing approaches that harm reduction could effectively address?

Marc Burrows: I mean, it’s kind of cool how it happened. That saying, “hindsight is 20/20” is a thing. I almost feel like a lot of things lined up in my life that I didn’t know at the time until looking back on it. I have considered myself a drug policy reformist, activist, or perhaps a disruptor. Someone who didn’t understand our drug policy in this country. My inclination towards this path has been developing since high school, although I didn’t recognize it at the time, nor did I know the terminology. These feelings were always there, even if I couldn’t articulate them then.

So, I had been formerly incarcerated several times, had many brushes with the law and the criminal justice system, and faced numerous challenges due to my criminal record. It was traumatizing for my whole family because it was a recurring situation where it was like, ‘Oh, Marc got arrested for drug possession. Now Marc is trying to get sober, and now Marc can’t get a job because of the drug possession charge.’ You know, it was that situation over and over again. So, the amount of obstacles was significant. People think it’s just about not being able to vote or own a gun, but it also affects other areas like college tuition assistance, applying for special licenses, such as becoming a licensed social worker, and obtaining professional credentials or degrees. I couldn’t even get an apartment lease. There were countless barriers. For instance, I couldn’t get a free checking account when I first got sober. And, of course, the employment issue was always the biggest challenge. So, there were just tons of barriers resulting from my criminal justice history.

You know, so that was one really challenging experience that informed my work. Then, another significant experience was contracting hepatitis C at 19 from being an IV drug user and not having access to sterile supplies. That diagnosis was devastating because I was ignorant and uneducated about hepatitis C. It rocked my world, affecting my intimate relationships, family, physical health, and mental health. When you have hepatitis C, you can live for 10 to 20 years with no symptoms, but the condition starts to creep into your life slowly. Every time you get sick, like with a common cold or the flu, you wonder if it’s being exacerbated by hepatitis C. This creates a constant paranoia about your health.

So, hepatitis C and my criminal justice history were significant touchpoints. The third major influence was my recovery journey. I chose a pathway called MAT (medication-assisted treatment) or MOUD (medication for opioid use disorder), using buprenorphine, Suboxone, or methadone. I still use this pathway today, but there is significant stigma against these medications within the recovery community and the addiction treatment industry. This stigma presented another major challenge.

Two years into my recovery, I began working in the addiction field, specifically at a high-end men’s sober living facility. I observed troubling practices, such as expelling residents following a relapse and dropping them off at the worst motels in Greenville. This approach was counterproductive and inhumane, particularly when individuals were at their most vulnerable and seeking help. Additionally, the program did not allow medications for opioid use disorder, so I had to keep my own recovery pathway secret while working there.

Lastly, a breakthrough treatment for hepatitis C called Harvoni became available. I had the opportunity to be cured, which was a huge milestone for me. Seeing all of this from the professional side of the desk, I realized that we needed to address the hepatitis C issue more effectively. The cost of treatment at that time was $90,000 for a cure (now it’s between $40,000 and $50,000). It seemed obvious that we should be providing clean syringes to prevent hepatitis C and reevaluating how we treat people with substance use disorder. Currently, we treat them like criminals and disguise punishment as treatment. Our policies are punitive and not aligned with how we address other health issues, like cancer. This realization was the culmination of my experiences and led me to advocate for change in both hepatitis C prevention and substance use treatment.

Being Cool: Peer-based Support

B. Arneson: What are your thoughts on providing care?

Marc Burrows: Social workers, nurses, peer support specialists, and others are trained to jump in and offer help constantly—almost to the point of inundating the person with assistance. However, based on my experience with Matthew, sometimes just being genuinely cool with the person can be more impactful. Sometimes, simply being kind and present is more effective than all the technical skills and interventions we’re trained in. I believe that’s the essence of why this approach works or, at least, it’s the style of work I want to practice.

Matthew never knew that I had lived experience because I would arrive from my office dressed in a button-up shirt, with my tattoos covered. After several interactions working with him, it came up in conversation that I had used to inject drugs. He was completely shocked, saying things like, ‘What? You used to do that?’ He was amazed that I had firsthand knowledge of those experiences. This moment underscored the importance of having people with lived experience in this field, as it creates a special connection that is hard to replicate otherwise. It has a profound effect on others when they realize that I am not just another social worker, but someone who truly understands their experiences.

Reducing Harm: Identifying the Successes

B. Arneson: Can you share a memorable experience that significantly impacted you?

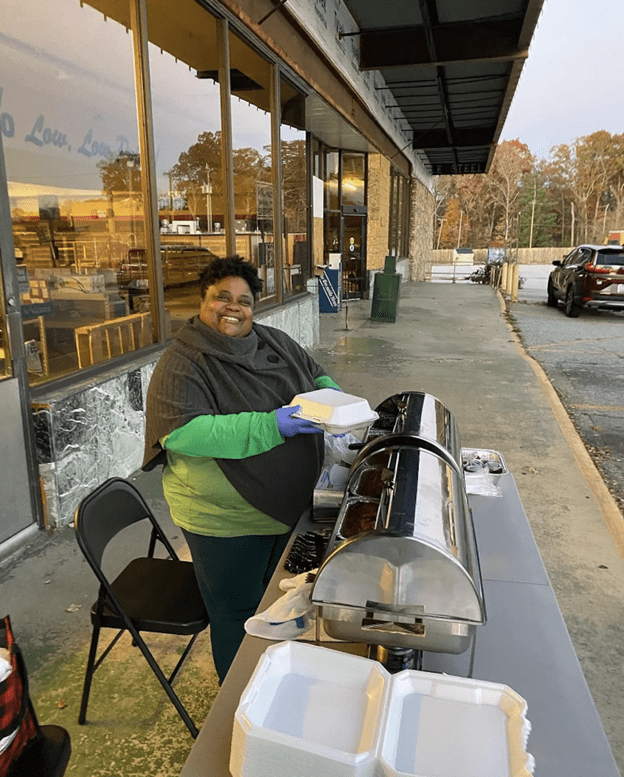

Marc Burrows: When someone approaches our mobile unit for the first time, there is often an awkward exchange. They usually try to gauge if we are trustworthy or if we might be undercover cops, fearing arrest. There’s a period of uncertainty where they question, ‘What are you guys doing here?’ After explaining our purpose, they often appear stunned, with a look of disbelief on their faces. Once we’ve clarified, I ask if they need anything, and we provide the necessary support. Despite the initial awkwardness, these interactions are profoundly impactful and can be quite magical. It’s rewarding to see individuals return and continue engaging with us.

For example, I remember one man who came to us for supplies and was tested, revealing that he was HIV positive. Receiving such a diagnosis is significant, and it was gratifying to be there for him during this challenging time. We also provide support for Hepatitis C diagnoses. Unlike my own experience, where I was informed of my Hepatitis C diagnosis over the phone with no guidance, we were able to offer compassionate support and connect him with treatment. This not only helped him personally but also contributed to broader HIV prevention efforts. By addressing issues like unprotected sex and needle sharing, we potentially prevented a significant amount of harm within the community.

Lastly, there’s a participant named Grace[1], who engages in sex work and is an IV drug user. She has been coming to us for support for as long as I have been involved in this work—about eight years. We have assisted her in numerous ways over the years.

B. Arneson: Do you feel that your work is becoming destigmatized? Has it become easier over the past 8 to 10 years?

Marc Burrows: But it’s, I mean, maybe it’s gotten more widespread. We have more support now, and we have supporters from higher places. We have champions or advocates in bigger positions who hold more influence, and that has really helped a lot. So, you know, it’s changed a lot. We’ve come a long way, although we still have a long way to go. When I started doing this work, people thought I was crazy. I was viewed as “the needle guy.” I was also working in MAT [medication-assisted treatment], so I faced both MAT stigma and syringe exchange stigma. My whole career has not been the easy way. I could have just jumped into abstinence-based treatment and not had any problems, but…

Much of this progress stems from our continuous effort to share information and advocate for expanding access to this intervention. Advocacy and public education are crucial; we regularly present and speak about our work, which helps spark what I call ‘dinner table conversations.’ After attending our presentations, people often discuss our programs, like syringe exchange, with their families. This grassroots advocacy, consisting of countless small conversations over the years, has significantly contributed to our current position.

Fostering a Collaborative World Through Care

Recently, I asked my brother if he had been using fentanyl again, and he broke down in tears as he admitted that he had. However, he also mentioned that he had kept the naloxone Marc provided him in his backpack. I am deeply comforted by the fact that my brother has this life-saving medication in close proximity to him. What began as an interview with someone who deeply inspired me evolved into a profound personal intervention. It forced me to confront the harsh reality that I could not rescue my brother from his addiction, but I can strive to support him in a judgment-free manner. Having already lost many loved ones to overdoses, including the loss of one of my childhood best friends earlier this year, I am profoundly concerned about the potential loss of my brother as well.

In 2023, overdose fatalities decreased by 3%, yet over 107,500 individuals still lost their lives to drug overdoses. Drug overdoses are completely preventable. Challenges Inc SC has achieved notable success, including distributing over 60,000 doses of naloxone and saving at least 1,128 individuals in South Carolina through its use. The efforts of Marc and his team at Challenges Inc SC compel us to reconsider the ways in which we have stigmatized our loved ones and community members struggling with addiction. While punitive treatments lack a solid evidence base, peer-based interventions offer a more effective solution.

Research shows that using peer support specialists has been linked to better health behaviors in different areas. For instance, Nyamathi et al. used peer coaches to encourage Hepatitis A and B vaccinations among unhoused men on parole. The study tried different levels of peer coaching, from lots of support—like weekly phone calls and in-person meetings—to minimal support, which acted as the baseline. The intensive coaching focused on improving self-management, assertiveness, and nonviolent communication. However, the study found that the level of peer support didn’t significantly affect vaccine completion rates.

Peer-based harm reduction programs are also effective in prisons. For example, Ross et al. studied 2,506 participants to see how well intensively trained peer educators could lead HIV prevention programs in 36 Texas prisons. The study found that prisoners in the program were more likely to admit they didn’t know their HIV status and wanted to get tested compared to those who didn’t participate. Additionally, Grinstead et al. conducted a randomized trial showing that peer-led HIV prevention education given before release significantly reduced risky sexual behaviors. Participants in the peer program were more likely to use condoms during their first sexual encounter after release and were less likely to use injection drugs or share needles within two weeks of release compared to those who didn’t receive the program.

In reflecting on Marc Burrows’ insights, it becomes clear that the true essence of providing effective care may lie not in the quantity of interventions but in the quality of presence. Marc’s approach underscores the profound impact that empathy and understanding can have. The research further validates the effectiveness of peer-based support models, highlighting their positive impact on health-related behaviors and outcomes both within and outside of prison settings.

So, rather than assigning blame, we should reflect on the underlying causes of these challenges. How can we collaboratively build a world where life offers more than incarceration and premature death? This is a sincere call to explore alternative approaches and to emulate the initiatives led by individuals like Marc, as these endeavors are vital for the well-being of those we care about.

To learn more about and support Challenges Inc SC go to: https://challengesinc.org/. To obtain naloxone at no cost, please visit: https://nextdistro.org/naloxone fbclid=IwY2xjawEWB99leHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHeJzffPIxlx-3jg7WJGRv2YroNJ0sRh54CBLuKwT6lVCkr1MuzeaGp7Wrg_aem_H4Q21DIgosJ3oXTvN7tnAQ

[1] The name “Grace” is a pseudonym used to protect the individual’s privacy