Public discourse is populated by zombie concepts—a term coined by Ulrich Beck to refer to tropes or claims that continue to live on even after hard evidence and history have long since killed them off, time and again.

One monstrous zombie concept is the claim that climate change will spark new atrocities and conflicts over food scarcity. It’s clear that climate change is a scientific fact. But I am a skeptic about any direct links between environmental crisis, climate change and conflict and famine in the modern world. This skepticism arises partly as a reflex against the poor arguments marshaled in favor of those who predict such crises. Not to mention the trend lines: as the globe has warmed over recent decades, mass atrocities (including both large scale violent killing and famines) have declined.

World population growth will predict future famine. No! Over the last 100 years, great and calamitous famines have declined almost to zero, while world population has expanded. The next wars will be over water. Not really. Research shows that transboundary water resources are a cause for cooperation more frequently than conflict. Darfur was the world’s first climate change war. A gross simplification of a complicated story that was more political than environmental. Ditto for Rwanda, Syria, or any other case one can mention.

Timothy Snyder’s Oped in the New York Times, “The Next Genocide”, exemplified the revenge of a dead idea. It invoked the Holocaust out of context—as a professional historian, Snyder surely should have known better! It presented environmental determinist accounts of the mass atrocities in Rwanda and Darfur as facts rather than folktales. It speculated about Chinese land- and resource-grabbing as if China had neo-imperial ambitions.

But, a discussion convened last week by the Stanley Foundation on this topic, made me reflect. The problem is not violence or starvation caused by scarcity, but how narratives of scarcity are deployed to rationalize aggressive policies. In responding to those narratives, political scientists and policy analysts have an important role to play—debunking not resurrecting the Malthusian specter. There is no reason to reconsider the verdict that the causal links between climate change and conflict are unproven, and should they exist, are mediated by a host of political factors. There’s no reason to overlook the basic rule that every mass atrocity is a political decision (and why are political scientists so poor at studying political decisions?).

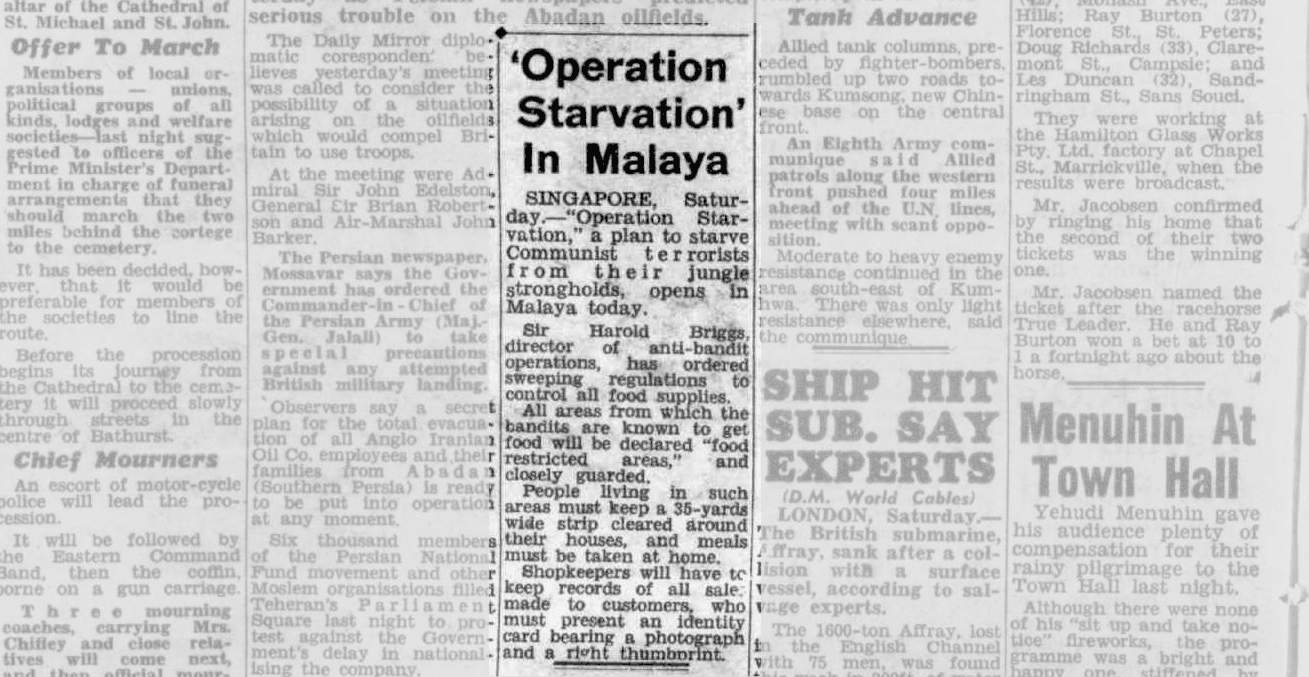

Malthusianism refuses to accept its proper place as a thoroughly disproven proposition. Refuted by every historical experience—not just food, but energy and minerals too—it is a story that refuses to die. But the un-death of Malthusianism is a political fact. Malthus’s Zombie holds an irrational but tight grip on our imaginations. Snyder’s Oped is just one example. There are plenty more: let me give just one example, prominent in the British media.

The renowned environmentalist Sir David Attenborough produced a TV program on human ecology two years ago, arguing that population control was a “huge area of concern”, and that the world was “heading for disaster unless we do something”.

“What are all these famines in Ethiopia?” he continued. The answer is, there are no longer famines in Ethiopia. The current drought—related to El Niño and exceptionally severe—is cutting several points of the country’s economic growth and has resulted in food scarcity and hunger, but not mass dying as in famines past. Thirty years ago a less widespread drought contributed to a famine that killed at least 600,000 people. The population has more than doubled in the meantime, but famines—in the sense of events that kill tens or hundreds of thousands of people—have disappeared from the country. Why? Because famine, like atrocity, is a political act.

The link between scarcity and atrocity passes through the minds and mouths of populist politicians. It’s political decisions that make something wholly insubstantial into something real.

Snyder might have chosen to make this point: Adolf Hitler’s unfounded fear of scarcity contributed to his hunger for lebensraum, and we should worry that similar irrational narratives may recur.

My simple recommendation to the advocacy and public information organizations who work on this is therefore, it’s our duty as political scientists and responsible citizens to challenge every public statement by a political leader or commentator who claims that resource scarcity threatens famine or atrocity. We may not be able to destroy Malthus’s Zombie—after all it is dead already—but at least let us immobilize this ghoul every time it makes an entrance, and stop it eating our brains.