“That we have established a tradition of holding transparent, open, and fair elections gives credence to our democratic bearing. That we have experienced peaceful transitions of government affirms our democratic temperament.”

– Bola Tinubu on Democracy Day, June 12, 2024

“Our politics has become a racket and our politicians, political racketeers.”

– Dan Agbese

On June 12, 2024, Nigeria celebrated its 25th year of unbroken democracy—a record in its history. Elections have become the path to office in Nigeria’s democracy, but few would describe them as free or fair. In 2022, in advance of the 2023 elections, only 23 percent of Nigerians said they trusted the Independent National Electoral Commission to carry out free and fair elections.

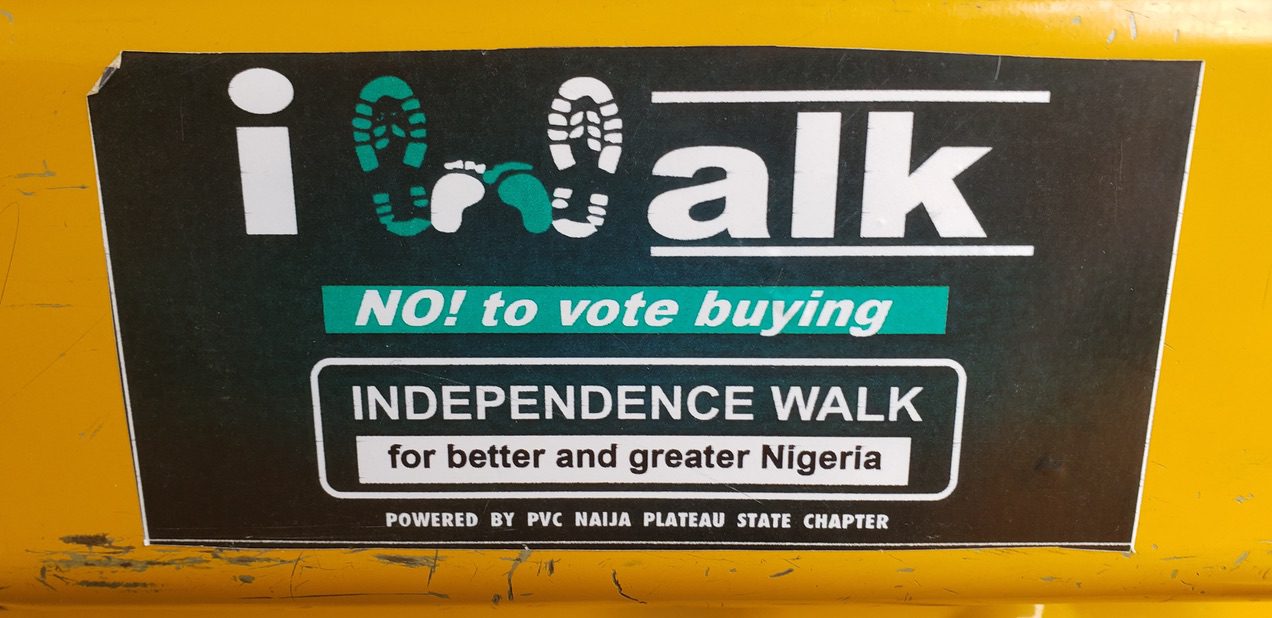

While elections may be celebrated in speeches, Nigerians and politicians alike describe them as competitions in electoral manipulation and vote-buying, with elected positions being sold on the auctioneer’s block to the highest bidder. As one Nigerian I interviewed described it, this was not the democracy Nigerians worked for; this was “criminal politics.”

Elections in Nigeria are emblematic of how transactional politics, meaning elite dealmaking, dominate Nigeria’s democratic institutions. In this way, Nigeria is an exemplary electoral political marketplace—a political system where political power is treated as a commodity that is bought, sold, and violently fought over. At times, negotiations over political power appear to align with formal democratic institutions and processes, while in others, they circumvent them. Elections are a key example. While elections take place, it is the backroom deals made among elite actors that determine who holds power. In this way, elections are a window through which the political system reveals itself.

In a new research paper, I analyze how electoral reforms and civic movements intersect with and are shaped by political marketplace competition using the Nigerian 2023 elections as a case study. By population, Nigeria is the largest electoral political marketplace in the world. It is also incredibly complex—exemplifying opportunities for democratic gains as well as the most destructive elements of political marketplace competition. These dynamics are not unique to Nigeria but are also at play in other electoral political marketplaces such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Iraq. The key findings from this analysis are summarized below.

Key Findings

- Elections are the market days of political marketplaces—presenting destructive competition as well as opportunities to reshape the system.

While competition for political power is constant throughout the political calendar, elections are the most important period—akin to a market day. Elections demarcate a unique opportunity to compete, rearrange alliances, and renegotiate deals in ways that are not possible outside of election periods. This is when political competition is the fiercest, embodying the most destructive elements of the marketplace—the monied deals, the short-sighted political thuggery, and the zero-sum politics. Given their importance, elections are also moments of opportunity to reshape the political system. In multi-tiered systems like Nigeria, political power is fractured, and no single actor controls the political system. This creates both opportunities and hurdles for democratic activists to transform the system.

- Violence and cash are key tools used to compete in elections, but these are contested and face opposition from the public.

Elections within Nigeria have been defined by the use of money and violence that manipulate and overshadow the will of the people. From party primaries, better known as “money bazaars,” to attempting to buy votes on election day, candidates rely heavily on the political loyalty that money, and lots of it, can buy. These costs are allegedly financed (directly or indirectly) with resources diverted from the state. Elections are also violent. Violence disrupted voting in 22 states, and the threats of violence likely contributed to low voter turnout. However, the election showed that the candidate who has the most money or willingness to use violence is not necessarily the one who will win the primary or election. Other factors are at play – notably a candidate’s political acumen and how these tactics will be received and contested by the public. Candidates with significantly less money or use of violence won states in heavily contested elections, suggesting that the utility of cash or violence varies across the country and may have limits.

- Electoral reforms can strengthen the voting process, but their implementation is subject to manipulation and can have unintended consequences.

The 2023 election cycle had a range of electoral reforms, such as the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System, the Election Results Viewing Portal, and currency swap, allegedly intended to improve the transparency of the process and mitigate common election rigging tactics such as ballot box stuffing and vote buying. However, the reforms faced varying levels of manipulation, logistical failures (intentional and not), and opposition that collectively decreased confidence in the election results. In addition, reforms such as the currency swap, partially aimed at attempting to cut down on vote buying, triggered an economic crisis for average Nigerians while elite politicians were still able to amass stockpiles of cash for election day. Electoral reforms within political marketplaces have the potential to reshape the rules of political competition, but they can also be manipulated or weaponized against opponents. In the process, average citizens may bear the consequences.

- There are crosscurrents that challenge the marketplace’s transactional politics.

The 2023 election cycle was historic in the emergence of a competitive, third-party candidate, Peter Obi, who drew nationwide support from voters and civic coalitions. His campaign harnessed long-standing grievances of poor governance and kleptocratic politics, offering a different political vision for the country. While Obi was no stranger to how the game was played, his campaign and the support it garnered was a major contrast to the dominant transactional mode of electoral competition. Although Obi did not win, it is striking how close he came to winning despite the opposition he faced and the levels of voter suppression and manipulation that occurred on election day. Obi’s campaign was significant, but the more important crosscurrents are the civic coalitions and youth engagement that emerged during the election. Many people “woke up” and engaged in politics for the first time. The key question is what comes next? Can the energy of the 2023 election be channeled and sustained in a long-term civic movement? Challenging transactional politics is extremely difficult, but Nigeria’s civil society remains one of the most promising drivers of change.

This paper is about the real politics that define Nigeria’s political system as exemplified during election periods. In exploring these dynamics, the paper seeks to shed light on how violence and money are used in elections, how markets respond to attempts at reforms, and the challenges and hope of civic movements within electoral political marketplaces.