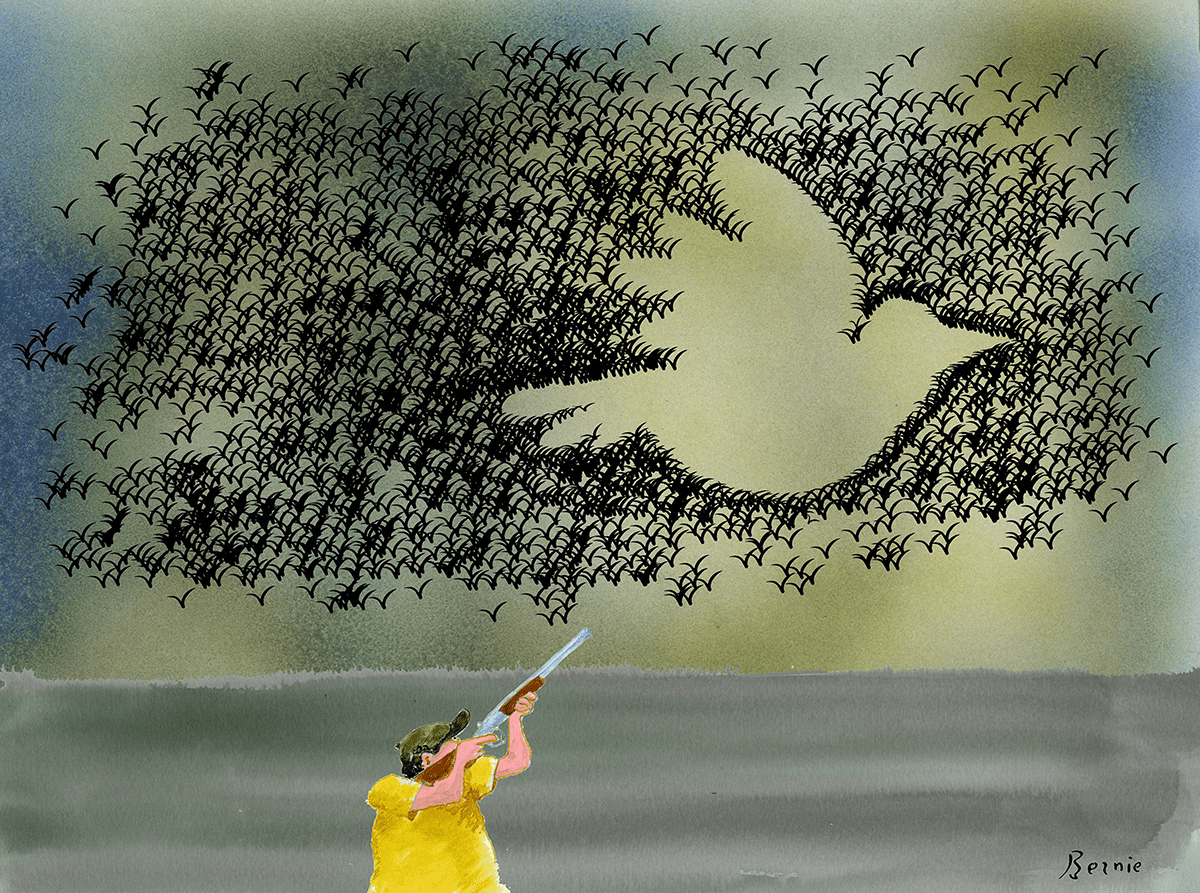

Protestations aside, the Nobel Committee had many reasons to pass over Trump for this year’s Peace Prize. In just eight months, Trump has dissolved the US Institute of Peace, rebranded the Pentagon the “Department of War,” and abolished USAID, a move medical researchers say could cause 14 million deaths by 2030. He has authorized over 500 airstrikes, many of which have killed civilians and violated international law, and sought to annex the Panama Canal, Canada and Greenland. And now, after sending billions in military aid to Israel and vetoing multiple ceasefire resolutions, Trump wants credit for bringing peace to the Middle East.

Simply from a procedural standpoint, there was virtually no chance the Nobel Committee would have – or even could have – rewarded Trump for his connection to the late-breaking Gaza deal. The nomination deadline for the 2025 prize came just 11 days into Trump’s term, which means that Trump probably did not make the candidate list to begin with.

The self-proclaimed “President of PEACE” argues that he deserves the prize for mediating eight peace settlements. Upon closer inspection, however, many of these are little more than trade deals masking as peace agreements. In some cases, they are but ceasefires coercively secured in the course of Trump’s tariff war.

This should come as no surprise – Trump’s policy approach has always been one of personal profit and power. The man behind The Art of the Deal (and his family) are estimated to have made $3.4 billion from his presidency through a combination of crypto, real estate, hotels, merch, and pressure on media companies.

And now, Trump has applied this mindset to his new-found obsession with securing peace (and Nobel Prize nominations).

Consider, for example, the two “peace deals” between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda, and between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The DRC-Rwanda deal excluded the 100+ armed groups who are actually fighting in eastern Congo – and failed to address the underlying factors that fuel the conflict. Rather, the centerpiece of the deal is a regional economic framework aimed at making Congo’s mineral economy more friendly for US investors.

With regard to Armenia and Azerbaijan, Trump claimed credit for a trilateral agreement which the three leaders merely “pre-signed.” The agreement excludes basic security guarantees and ignores the 2023 ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh. What it does do, though, is establish the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP), a transit corridor to which the US will have exclusive development rights for a period of 99 years.

Other Trump “peace deals” are of a similarly transactional nature. Take Trump’s claims to have stopped wars between both Cambodia-Thailand and India–Pakistan. In both cases, he threatened to end trade talks if the parties failed to reach a ceasefire. For this, the leaders of both Cambodia and Pakistan nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize. But When Trump suggested that India follow suit, India’s Prime Minister refused, claiming that the agreement came about “bilaterally.” Trump then reduced tariffs on Cambodia, Thailand and Pakistan to 19%, while increasing India’s to a crushing 50%.

Other world leaders quickly cottoned on to the idea that Trump looks favorably upon those who flatter him. At a lunch with five African presidents in July, four of the leaders said they would support Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize, and four of the five made a point to market their country’s rich mineral deposits.

And with respect to Gaza, despite a promising (and over-due) ceasefire, the long-term prospects are also concerning. In recent weeks, Israel’s far-right finance minister spoke of Gaza as a “real estate bonanza,” and Trump seems to agree: featured in his 20-point Gaza peace plan is a “Trump economic development plan” and a “special economic zone” with “preferred tariff (rates).”

Trump’s populist peacemaking raises a red flag for peace diplomacy elsewhere. In Myanmar, a genocidal military junta stands accused of widespread human rights abuse as the country remains locked in civil war. A recent report suggests that both the junta and the KIA rebel group are courting Trump with promises of a rare earth mineral deal.

And then there’s Ukraine, where Trump failed to keep his promise to solve the conflict in 24 hours, and made little progress on peace at the Alaska and White House summits. Now, he seems more interested in negotiating mineral access than in pursuing an acceptable peace.

Trump’s approach hews to what Sara Hellmüller and Bilal Salaymeh term “transactional peacemaking,” focused on short-term bilateral interests rather than comprehensive efforts to confront underlying issues. The drawback, according to these authors (and those they draw on), is that a transactional approach shortchanges institution-building. The most powerful players will seek gains through (potentially corrupt) side deals and “peace” – like the war that preceded it – then resembles a rush for spoils.

Perhaps at some future point in time, Gaza City will become a “thriving modern miracle [city]”, or Eastern DRC the beating industrial heart of central Africa. Maybe then, the Nobel Committee will give a nod – and a prize – to the leader who dreamt of such outcomes. But first comes the arduous and uncertain work of guaranteeing security while rebuilding institutions, trust, and lives – the real stuff of peace that President Trump never seems to mention.