My research over the past year has returned to a topic I once spent a great deal of time thinking about: memorial museums. And so I took advantage of a recent trip to New York City to tour, for the first time, the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

The events of September 11th – and hence the museum and memorial – unleash for many, myself included, a complex and unsynthesize-able set of emotional, political and intellectual issues. On the day in 2001, I was working at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC and could see the smoke rising from the Pentagon as I, along with the entire city frantically tried to figure out how to get home while being fundamentally incapable of processing the enormity of what seemed to be happening in New York, Pennsylvania, and across the river. The events of that day resonated with confusion, trauma, and disbelief. These emotions turned to sadness over the loss of life; and anger over the eventual political and military turn, the frightening triumph of an intelligence-security apparatus and the re-legitimization of war, in the context of what often feels like an unstoppable mushrooming of violent acts. Whatever the meaning one might bestow on the date 9/11, it surely separates before from after. For me, the power of the memorial and museum is that they mimic and refuse to resolve this mix of emotions.

The museum is located on the memorial plaza, sixteen acres on the site of the former World Trade Center complex. More than 400 trees encircle the two memorial pools, each nearly an acre large, within the footprints of the former twin towers. I expected to be awed by the memorial pools and instead found them jarringly grandiose, with the names of people killed in the attacks etched on their perimeters an incomplete gesture to humanize the space. While the surrounding trees and use of water were intended to denote the space coming back to life, surrounded by Manhattan’s splendor and opulence, these largest of manmade waterfalls in North America, the pools did not provoke a sense of loss, but rather of alienation from the scene itself. The brilliance of their design (and it is unquestionably brilliant)—with its fathomless center—and the scale of their expanse marks territory with the cold arrogance of a global center of financial power. This, of course, is part of the memorial; terrorists selected the site as a target because of the concentration of power into the structures that once rose above the now consecrated footprints. Where soaring towers once intended to awe with power, now pools of grief take their place, suggesting the same goal of provoking awe for a city’s ability to mourn in splendor.

The museum is structured like trauma itself, a descent into a massive cavern populated by images, objects and narratives that all feel familiar and which haunted the day and era that followed. The architecture adamantly insists on overwhelming the visitor as the ramp leads into the chasm of the structure. As one descends, the journey into the pit offers only a few curatorial handholds—content, as if it fluttered from the sky, offering piercing glimpses of the story that is starting to be told.

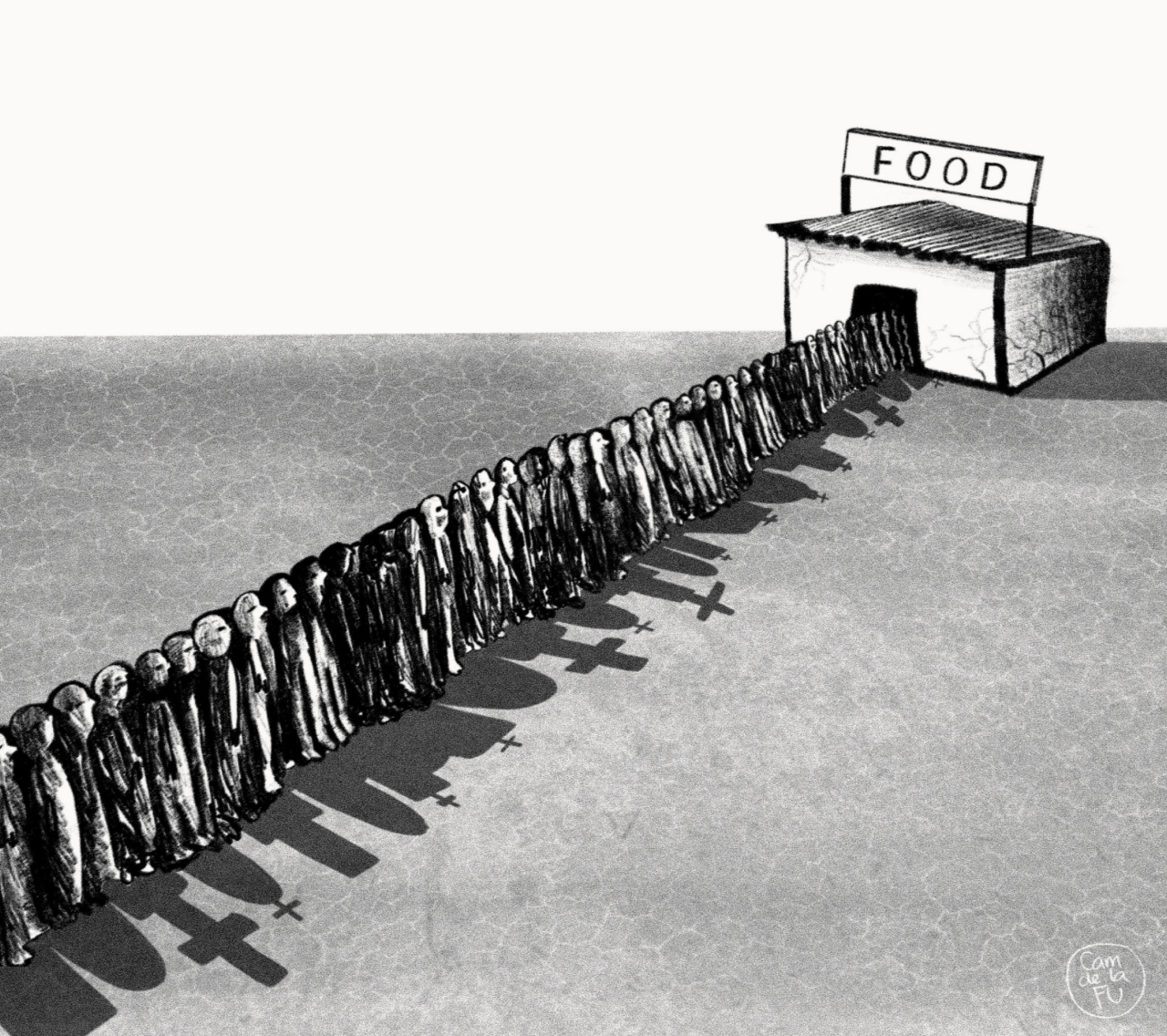

The scale of the chasm at the bottom–what the museum calls Foundation Hall, a space ranging from 40 to 60 feet and including nearly 15,000 square feet of floor space–is intent on dwarfing it all. There, no matter the size of the crowd among which one finds oneself, the visitor is shrunk to a meaningless, awed, and disoriented individual. Memory, the museum seems to announce, is not as you experienced it but as imposed by forces beyond your control. Although words on the wall tell you, that “No day shall erase you from the memory of time”, what the structure communicates is that you never really mattered in the mix of forces that constitute history. The towers represented a power beyond individuals, their destruction a desolate choice that struck without warning to the people who were killed, and, as we now know, the global war on terror a projection of willful violence that expands without borders. A world that had begun to see the decline of armed conflict would henceforward reverse course.

But “In Memoriam”, the memorial to the individuals killed that day introduces a different experience. There, in the emotional core of the museum, the faces of the individual lives lost a human story begins to unfold. Here, mourning is no longer abstracted but embodied: names, faces, working class, privileged, men, women, white, Hispanic, black, Asian…each face speaks of an interrupted story. In so doing, the display turns towards love; the people are invariably pictured through images selected by the people who cared deeply about them and one feels, suddenly, the absolute loss. Finally, one begins to see that the memorial and museum gesture not only to place of New York City as a global capital but also to its place as a living and breathing human community. New York City is a glamorous skyline, but it is also home to 19 million people populated with quirks, routines, privilege, poverty, struggle, hopes and failures that are human life. These are its people.

The historical exhibition for a visitor who was old enough to live through that time period feels shockingly familiar. The images of the day are pressed into our minds, dissected and re-broadcast over and over. To visit is to revisit and the museum curators’ decision, rightfully so, to portray the history with fidelity to the timeline and minimal adventure into meaning beyond the day’s losses, is a refusal to resolve any of the larger issues. I found myself overwhelmed by recollection and by encountering new folds within the familiar story among the objects, images and narratives. Debates have raged and will continue to disrupt the exhibition and the interpretation of events of 9/11, but the museum ultimately walks a careful line.

This memorial and museum follow the trend to negative form memorials, those premised on what James E. Young describes as “uncompensated loss and absence” (3), the signature of which is Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial but which also includes as many Holocaust memorials (certainly the memorial to the Denkmal for Europe’s Murdered Jews). These memorials, he argues, simultaneously mark the longing for and the inability of contemporary societies to postulate unity identity, let alone to build a memorial to one. What he describes as memorials that posit a nation’s ‘collected memory’ as opposed to ‘collective memory’ embrace of democratization of memory forms, no longer in service of a common abstracted identity, but “actually ours” (15). For Young, this introduces a redemptive quality, ultimately privileging “the value of life in its quotidian unfolding” (16). This appears to be the goal of the overarching experience at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. For me, it remains an open question. I did not arrive at resolution, the sum impact was the sense of ambivalence about the fate of individuals in the course of history. In any case, without resolution, the history simply stays with you and continues to haunt, as it should.

Notes:

Young, James E. 2016. The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss and the Spaces Between. University of Massachusetts Press.