This is the first half of a two part extended version of an essay published in the London Review of Books (39:12, 15 June 2017, pp. 9-12).

In its primary use, the verb ‘to starve’ is transitive: something people do to one another, like torture or murder. Mass starvation on account of the weather has all but disappeared: today’s famines are all caused by political decisions, yet too often, journalists use the phrase ‘man-made famine’ as if it were a surprise.

Over the last half century, famines have become rarer and less lethal. Last year I wrote in the New York Times that they might be abolished for good.[1] But this year, mass starvation is back and we face the possibility of four or five simultaneous famines in the world. In March, the then head of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the East-African born former Tory MP Stephen O’Brien, told the Security Council that ‘we stand at a critical point in history. Already at the beginning of the year we are facing the largest humanitarian crisis since the creation of the United Nations.’[1] ‘Critical’, I’d argue, not because it is the worst crisis of our lifetime, but because a long decline – seven decades –in mass death from starvation has come to an end; in fact it has been reversed.

O’Brien had no illusions about the causes of the four famines, actual or imminent, that he detailed in north-eastern Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen. In each case, the main culprits are wars fought in ways that destroy farms, livestock herds and markets, and commanders’ decisions to block humanitarian aid.

In Nigeria, communities caught up in the war between the extremist group Boko Haram and the army have been stripped of assets, income and food; besieged and isolated, they starved.

As the Nigerian army slowly rolls back the areas under Boko Haram control, they find small towns where thousands starved to death last year. As the counter-insurgency grinds on, the food security and nutrition specialists who compile the data that are fed into the blandly-named ‘integrated food security phase classification’ (IPC) system, are fearful that in this year’s ‘hungry season’, approximately from June to October, communities in the war zones will again be dragged up the gradient of the IPC scale: from level four (‘humanitarian emergency’) to five (‘famine’). Last year in Nigeria, the UN and relief agencies can say, they didn’t know the full extent of the crisis, pleading innocence through ignorance. This year we have been given due warning.

In South Sudan, government and rebel armies have fought their civil war less against one another than against the civilian population. In the summer of 2016, evidence from aid agencies showed nutrition and death rates that met the criteria used by the UN for determining that a food crisis had reached famine levels. Fearing that declaring ‘famine’ would antagonise the South Sudanese government, already paranoid and cracking down on international aid agencies—including robbing, raping and murdering aid workers—the UN and other humanitarians prevaricated. By February, even the veterans of South Sudan’s horrendous famines of the 1980s were saying that this was as bad as anything in their experience, and perhaps worse. The government’s lack of mercy was no longer open to doubt, even among the most stubborn optimists. The UN duly declared ‘famine’.

Yemen is the biggest impending disaster, possibly the famine that will define this era. Don’t be fooled by pictures that show hungry people in arid landscapes: this is entirely a famine crime, and the weather had nothing to do with it. More than seven million people in Yemen are hungry. The number of Yemenis likely to die of starvation and disease is far greater than those dying in battles and air raids. The coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates has strangled the country’s economy. Before the war, eighty percent of Yemen’s food was imported, mostly through the Red Sea port of al-Hudaida. At Saudi insistence, backed by the US and the UK, the UN Security Council imposed a blockade on Yemen. There’s an exemption for food, but the inspection procedures are slow and laborious. Saudi aircraft bombed the container docks at al-Hudaida so that all ships must now be unloaded the old-fashioned way, using derricks and stevedores. Roads, bridges and markets have been damaged or destroyed, slowing commerce to a crawl. The Bank of Yemen, relocated from the Houthi-controlled capital Sana’a to the enclave controlled by the recognized government, no longer pays salaries. The Houthi forces aren’t innocent either: they impose their own blockades, notably laying siege to the highland city of Taizz. Food is the biggest weapon, and lack of food the biggest killer, in the Yemen war.

Unlike their blunt statements on war crimes in South Sudan, UN and aid agency statements on Yemen are muted: it’s hard to escape the conclusion that they feel unable to criticize Security Council decisions. While the famine deepens, the British and American navies persist in helping enforce the blockade and diplomats at the Security Council discuss how they could recalibrate the embargo. All are in danger of becoming accessories to starvation.

Only in Somalia does a modicum of blame attach to drought—though the ongoing war between a coalition of north-east African armies and the militant group al-Shabaab is primarily responsible for the immiseration of the worst-affected areas in the south of the country. Until this year, Somalia had the sad distinction of being the only country this century where the UN had declared ‘famine’: that was in 2011. In their recent book—which should be compulsory reading for all concerned with today’s humanitarian crises—Dan Maxwell and Nisar Majid describe this famine as a ‘collective failure.’[i]

To war and drought we should add incompetence on the part of the Somali authorities and corruption. A final element in the 2010-2102 famine — still rankling in the memories of aid professionals who struggled to halt an eminently preventable disaster — was the restriction on humanitarian work imposed by the USA Patriot Act of 2001. Intended to criminalise support — material or symbolic, deliberate or inadvertent — for any group on the terrorist list, the Patriot Act meant that it was practically impossible for an aid agency to operate in the famine-stricken area without risking prosecution in a US court. This applied not just to American agencies, governmental and private, but to the UN and anycharitable organisation. In principle, if al-Shabaab hijacked a truckload of food provided by an agency such as the Red Cross, that agency would be criminally liable. Even the threat of prosecution posed a reputational risk that aid agencies weren’t ready to run. Staff in USAID and the State Department worked assiduously to find a way around this provision, but the Justice Department was immovable until the UN’s declaration of famine prompted belated agreement on a workaround. In the eight months that it took the DoJ to come up with the formula, the world’s biggest aid donor shipped no food to Somalia. Perhaps 260,000 Somalis, mainly children, died. Most if not all of the deaths could have been prevented if the Obama Administration had been more alert to a disaster caused by its decision to prioritise counter-terror in this inflexible way.

The humanitarian workaround—‘carve out’ is the term that’s used—of the Patriot Act is still in place. But it’s provisional and unclear, and the broader chilling effect of security surveillance of humanitarian actions in places such as Somalia, Syria and Yemen, has not changed. Feeding the hungry, treating the sick, and tending to strangers in need, are all subject to security screening. It’s not only burdensome and intrusive, but deters the kinds of energetic and creative aid work that is needed to provide relief in these crises.

Perhaps even more damaging has been the clampdown on money transfers. Remittances from the diaspora contribute at least 30 percent of Somalia’s national income, and in the absence of a normal banking system, the funds are transmitted through companies that use the hawala system. The businessmen who run these corporations are interested in profit not ideology but the approach of counter-terrorists since 2001 has been to target them as possible accomplices to terror, rather than treating them as commercial service providers who might be ready to cooperate in a regulatory framework that serves everyone’s interests. Since November 2001, when the US shut down al-Barakaat, the biggest of these companies, on (unfounded) allegations of being involved in terrorist financing, the Somali financial sector has been – as a consequence — the commercial banks’ refusal to do business with them.

Even as we acknowledge that drought and crop failure are playing a role in this year’s hunger in Somalia – level 4 ‘humanitarian emergency’ on the IPC scale today, but threatening level 5 famine in the coming months – we shouldn’t overlook the fact that a much more widespread drought in neighbouring Ethiopia last year passed off without famine because of an expeditious relief effort led by the government. At the peak of their effort, the Ethiopian government and the UN World Food Programme were feeding 18 million Ethiopians, a higher number than the in-need populations of all the four countries on today’s danger list. There’s nothing natural or inevitable about people dying from hunger when the rains fail.

That’s a fact that can never be repeated too often, because it corrects the most common misconception about famine. Try a Google images search for ‘famine’ or ‘starvation’ and by far the single most common pictures that pop up are of hungry African children. You will find images of droughts and deserts, illustrations of the Great Famine in Ireland and distastefully-posed black-and-white photographs of colonial era famine victims, but very few images of war or of deliberate starvation. When I tried this, from the top 250 images (125 ‘famine’ and 125 ‘starvation’), just two showed scenes of war. Two showed pictures from Nazi concentration camps and a handful were from the starvation inflicted during the World Wars and the Russian civil war of 1919-21. The Google search straw poll points to the black hole at the centre of our intellectual history of the ideas of famine and starvation.

My organisation, the World Peace Foundation, has compiled a catalogue of every case of famine or forced mass starvation since 1870 that killed 100,000 people or more (so-called ‘great famines’).[ii] There are 61 episodes in this list, which in total killed a minimum of 105 million people. About two thirds of the famine deaths over the last 147 years were in Asia, about 20 percent in Europe and the USSR, just under 10 percent in Africa. The biggest killers on record were the vast political famines, among them the gilded age famines (aptly called ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’ by Mike Davis[iii]), the Great War famines in the Middle East including the forced starvation of a million Armenians, the Russian civil war famine of 1919-21, Stalin’s starvation of Ukraine during 1932-34 (now known as the Holodomor), the Nazi ‘Hunger Plan’ for the Soviet Union, the Chinese civil war famines, the starvation inflicted by the Japanese in World War Two, and Mao’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ of 1958-62, the largest famine on record, which killed at least 25 million people.

Yet these political famines seem scarcely to register in our collective imagination. They are strikingly absent from the canon on which theories of famine and policies for food security have been constructed. Even Amartya Sen did not take them into account when developing his ‘entitlement theory’ of famine causation, which correctly overturned explanations of famine based exclusively on food shortage.[iv] In the WPF’s catalogue of great famines, 72 million deaths occurred in episodes in which famine was used either as an instrument of genocide or recklessly inflicted by government policy. Ignoring these famines, or misclassifying them as caused by natural disaster, is an error—as though the history of democracy were written without mention of the United States, or life on planet Earth without including the oceans.

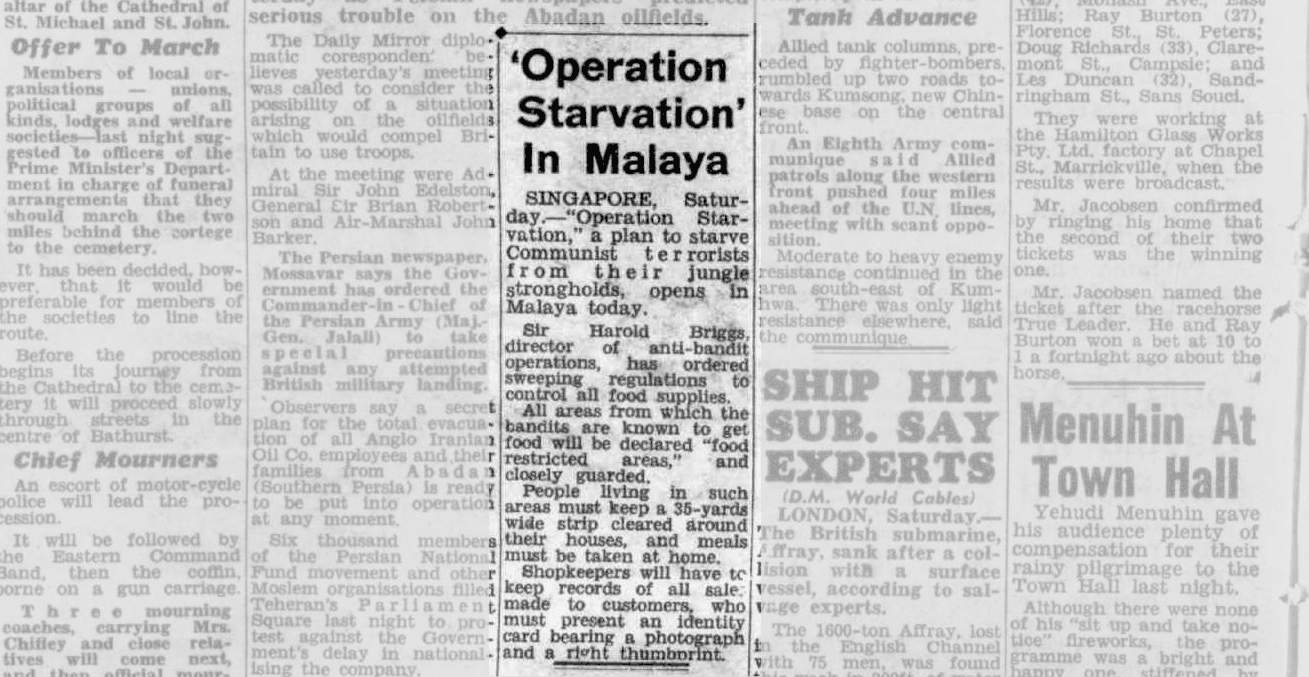

The full essay is also available as a pdf: Operation Starvation (extended).

Notes:

[i] Famine in Somalia: Competing Imperatives, Collective Failures, 2011-12, by Daniel Maxwell and Nisar Majid. Hurst, 2016.

[ii] [[http://fletcher.tufts.edu/World-Peace-Foundation/Program/Research/Mass-Atrocities-Research-Program/Mass-Famine ]] The definition of ‘great famines’ is from Paul Howe and Stephen Devereux, ‘Famine Intensity and Magnitude Scales: A proposal for an instrumental definition of famine,’ Disasters 28/1 (2004) 353-72.

[iii] Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, London: Verso, 2002.

[iv] Amartya Sen, Poverty and Famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1981.