Published June 21, 2021 in The Baffler, read the full excerpt at, The Unwinnable War on Disease.

In my book New Pandemics, Old Politics, I tell the history of the modern world in four pandemics. It begins with cholera in nineteenth-century Europe and South Asia and continues with the Great Influenza of 1918–19 and HIV/AIDS in Africa and Western countries. The fourth case is “Pandemic X” a.k.a. “the next big one”—the feared and imagined coming plague against which we have been constructing defenses for the last twenty-five years. Those defenses failed to stop Covid-19. Doubtless the world could have done much better, especially had there not been a dedicated skeptic of science in the White House. But I worry that in choosing to “fight” infectious microbes to “defend” our way of life, we are locking ourselves into a conflict we cannot win.

I use the “war on disease” as an organizing principle to examine two centuries of scientific thinking about epidemic diseases and the politics that have shaped the responses to each pandemic. As the title of the book indicates, each pandemic is new—indeed its newness is its defining characteristic—while the political and social responses to it are dully predictable. One pattern is that no pandemic is “natural”: each killer pathogen evolves and spreads in an ecology that we ourselves have engineered. For cholera and HIV/AIDS, it was European conquest and the reorganization of colonially subjugated societies for the profit of their imperial masters. For influenza, it was the organization of total war.

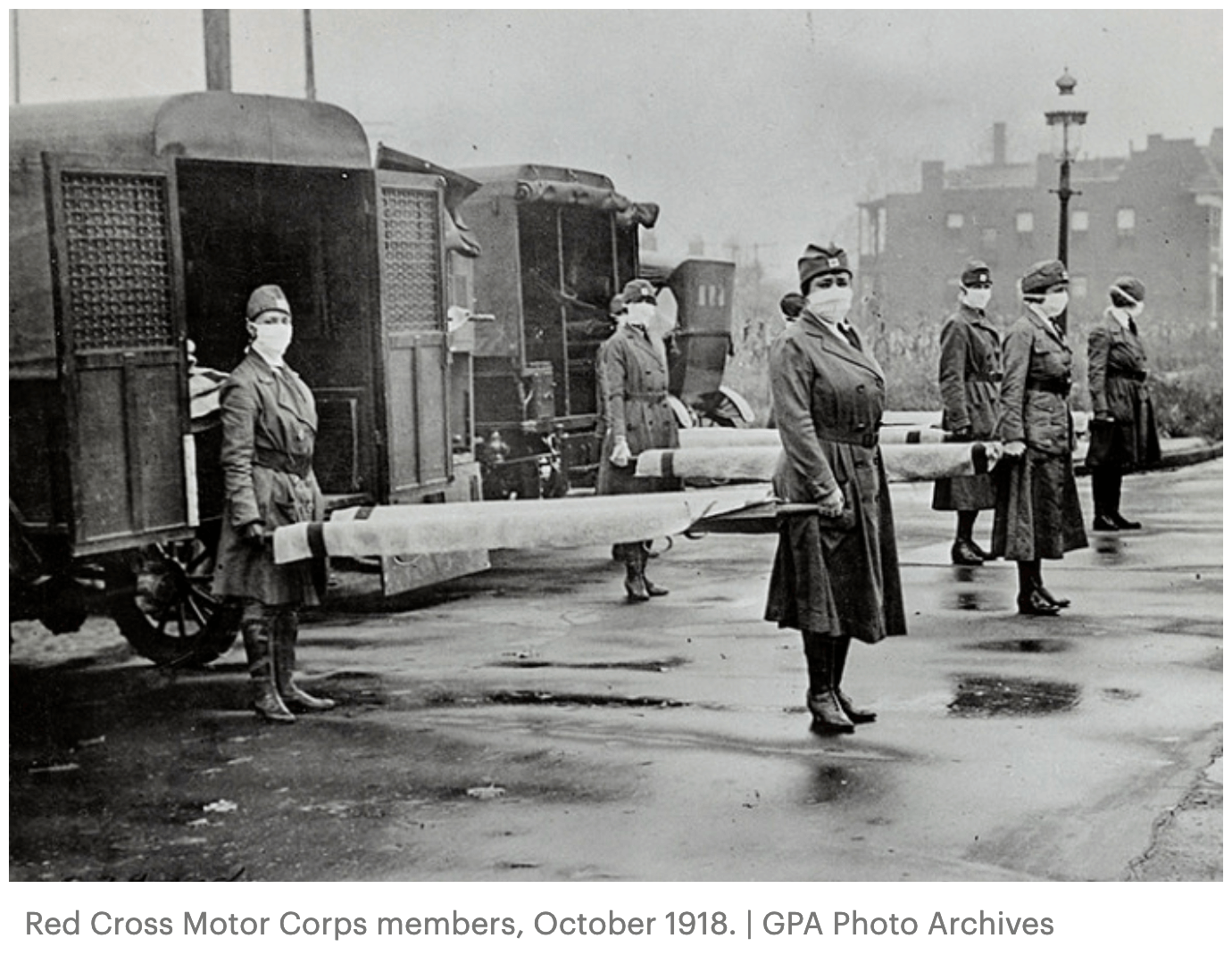

The excerpt below is from the chapter on influenza. It illustrates the irony of approaching the greatest pandemic of the twentieth century through the lens of the “war on disease,” because it was in fact the war itself—and specifically the advances in military hygiene and infectious disease control—that created a unique ecology in which this exceptionally virulent strain of influenza could evolve and spread.

Photo: Battling the flu pandemic 1918, GPA Photo Archive (CC BY-NC 2.0)