Last week’s report from the United Nations, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025, opened with a counter-intuitive headline: ‘Updated global estimates point to signs of a decrease in world hunger in recent years.’

Yes, that’s correct. The report explains that the percentage of the world population suffering food insecurity and hunger is falling year by year. In 2022 it was 8.7 percent, in 2023 it was 8.5 percent and last year it was estimated at 8.2 percent.

This isn’t hard to explain. It’s partly a matter of regional variations—hunger is worsening in parts of Africa and the Middle East even while it is declining in Asia. But the finding also holds at a level of greater granularity.

In previous posts, we have drawn on the historic data for famines and shown how they have multiple, complicated, often idiosyncratic causes, and how ‘world food crises’ have only limited associations with famines. This blog post uses two other leading food security indices (not those used by the UN) and examines how they relate to the famines in the World Peace Foundation great famines dataset as well as those examined by the Famine Review Committee of the IPC. (The figures below use datapoints from both famine datasets, though they represent different things.) Nonetheless the broad-brush comparisons are instructive.

Global Food Security Index

First is the Global Food Security Index produced by the Index Economist Intelligence Unit (unfortunately it only goes up to 2022). It has four components:

- Availability (agricultural production, risk of food supply disruption, national capacity to disseminate food).

- Affordability (ability of consumers to purchase food, their vulnerability to price shocks, and presence of safety net programs).

- Quality and safety (variety and nutritional quality of diets, safety of food).

- Sustainability and adaption (exposure to climate and natural resource risks and adaptation to those risks).

It’s therefore a good measure of the overall health of a country’s food economy, while the food availability and affordability indicators relate directly to factors closely associated with famine. It lacks data for Somalia but is in other respects comprehensive.

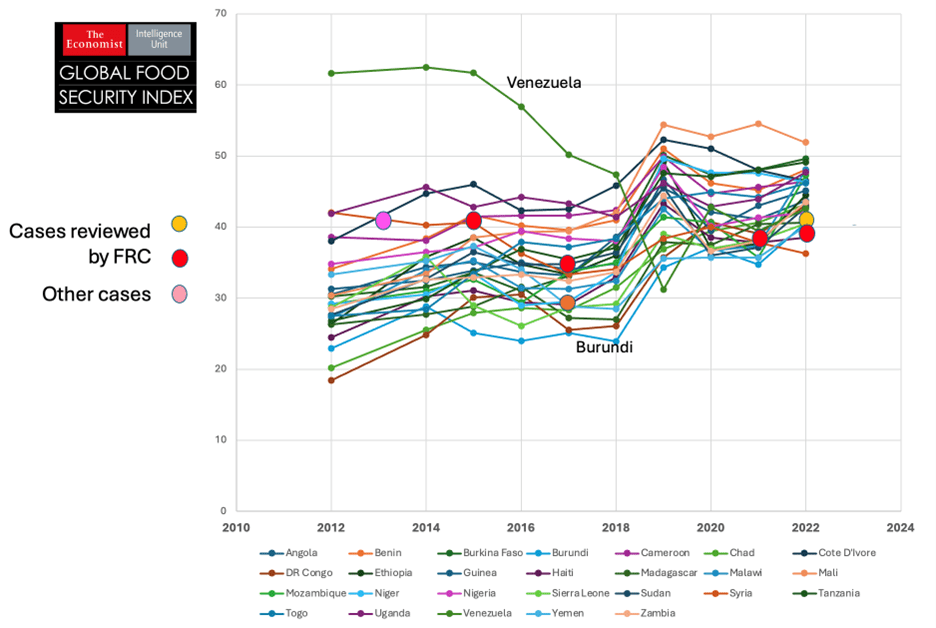

Figure 1 shows the Food Security Index scores for selected countries for 2012-2022, with the cases examined by the Famine Review Committee of the IPC (red indicating a war famine, yellow the drought in Madagascar, and brown the food emergency in Somalia) and cases (pink, the onset of the humanitarian emergency in Syria).

Figure 1: Food Security Index Scores, selected countries 2012-2022

Two things are notable about this figure. First, food security scores generally improved over the years, with notable exceptions being Syria and Venezuela. Second, while the cases identified as famines or potential famines are all at 40 or below on the FSI, they are not among the very worst cases. Burundi, most of the time the worst-scoring country, has not had a FRC review.

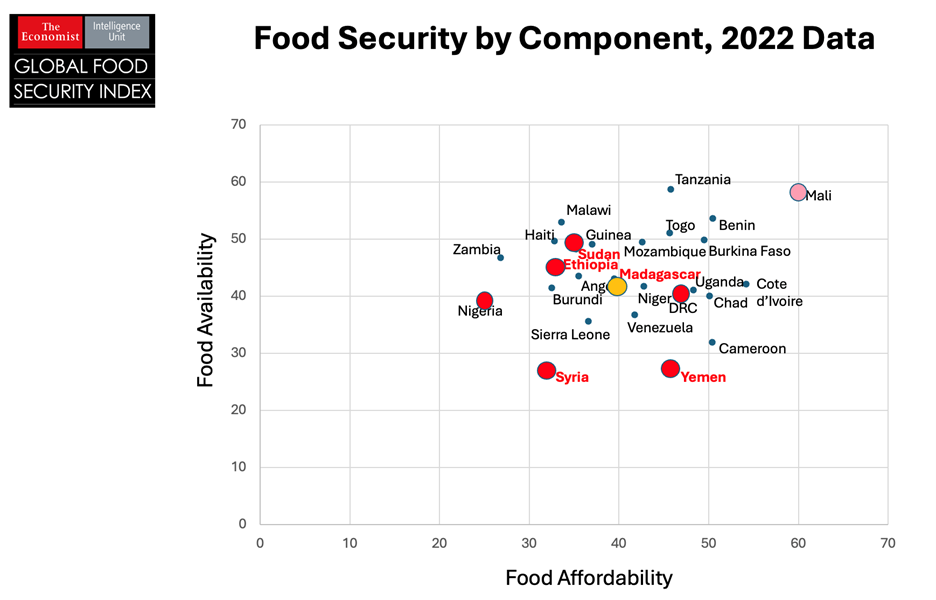

Figure 2 takes the food availability and affordability scores for selected countries for 2022, and identifies the cases for which the FRC was convened during the ten years prior, plus other cases of concern (DRC, Nigeria, Mali).

Figure 2: Food Availability and Affordability, Selected Countries, 2022

It’s clear that the two lowest-ranking countries for food availability—Syria and Yemen—are also famine-stricken, and the lowest-ranking country for food affordability—Nigeria—also suffered famine. But the match is incomplete. Cases such as Sudan and Ethiopia were not among the lowest ranked on either indicator.

These associations don’t show causality. So the collapse of food availability in Syria (especially) and Yemen is not a ‘cause’ of mass starvation in those countries, so much as it is associated with that outcome, jointly produced by the same war-related factors.

Global Hunger Index

The second index we will use for comparison is the Global Hunger Index, produced annually by a consortium of hunger-focused voluntary agencies. The GHI is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger. It uses indicators for undernourishment (share of the population with insufficient caloric intake), child wasting (low weight for height, hence acute malnutrition) and stunting (low height for age, hence chronic undernutrition), and child mortality, to provide an overall assessment of the nutritional health of the population.

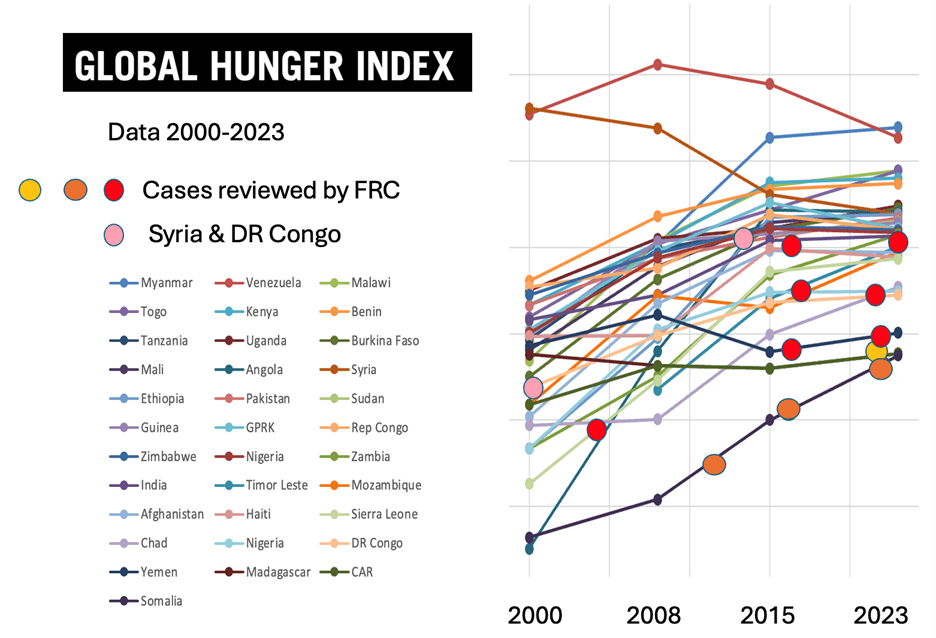

The hungrier the country, the higher the score given by the GHI, so the following figure inverts this to place the better-off countries at the top and the worse-off at the bottom. Figure 3 plots GHI scores for selected countries (again, chosen because they are either poor and hungry, or because they have been stricken by famine), from 2000 to 2023.

Figure 3 Global Hunger Index Scores and Famines

In comparison with the GFSI, there appears to be a closer match between GHI scores and famines, which is to be expected as the GHI and IPC use overlapping measures of child malnutrition and mortality.

What we see is, once again, a general improvement in nutrition across those years, at the same time as there is an increase in famines during the same period. Somalia (which is included in the GHI but not the GFSI) ranks as the hungriest country. Yemen and Madagascar are cases with no improvement over the years, becoming the focus of Famine Review Committee reviews of IPC data in 2016 (Yemen) and in 2022 (Yemen and Madagascar). The other country with no improvement is Venezuela, while Syria stalled in 2011 after improving in the first decade, and Haiti had a marked deterioration. (Venezuela and Haiti began with the best scores in 2000.)

Reflections

The general findings from these comparisons point to one conclusion that is well-established and a second that is important, but counterintuitive.

First, famines tend to strike countries with the lowest scores on these indicators. But the causal connection isn’t straightforward.

Second is an intriguing but consistent finding: the increase in the number of famines is occurring despite an overall increase in global food security and nutrition indicators. This is the headline of last week’s UN report. We also saw a similar disjuncture in the global food price data. Even while global food security—across a swathe of indicators—is improving, the incidence of famines is increasing. This tells us that the global food security is more volatile and unequal. That’s consistent with hunger being used as a weapon.