There are a lot of unanswered questions about the war in Ethiopia. Let me pose one more: who stands to gain across the region?

Ten years ago the then-Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Meles Zenawi told me, “my nightmare is that we should have an Egyptian agenda financed by Gulf money.” He didn’t foresee state-of-the-art military technology as part of that nightmare.

The crucial military difference between the Federal army and the TPLF in the current war is armed drones flown from an airbase in Assab. A drone campaign of this nature will have required meticulous advance planning. The airbase is operated by the United Arab Emirates, formerly used as a base for its military operations in Yemen.

Under President Donald Trump, U.S. policy has been to give free rein to its key allies in the region—Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In a phone call with Israeli and Sudanese leaders on 23 October President Trump said, of Egypt and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, “And they’ll end up blowing up the dam. And I said it — and I say it loud and clear, ‘They’ll blow up that dam’.”

We don’t know whether President Trump was briefed about preparations for drone strikes in Ethiopia, but he certainly sent a loud and clear message to his allies in the Middle East. Those allies knew they couldn’t expect such latitude from a Biden Administration.

For Egypt, Ethiopia in turmoil is a return to the status quo ante before Meles was in government—something they desired. A strong Ethiopia challenges Egypt’s control over the Nile Waters and its agenda for influence in the region. Egypt also has a quarrel with the African Union, which suspended it after President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi seized power in 2013. (The AU automatically suspends governments that take power by unconstitutional means.)

For the UAE, a weakened Ethiopia as a commercial-military dependent would fit in with its overall designs on the region.

Let me reiterate: I am not assigning culpability or direct involvement to either of these countries. But they stand to gain.

The most immediate beneficiary of the war is the Eritrean president Isseyas Afewerki. He has longed for Ethiopia to be in turmoil. In the 1990s he described Ethiopia as like Yugoslavia, destined to fragment. His two biggest fears are the Ethiopian army and the TPLF. Today they are locked in mutual annihilation.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was perhaps a little naïve, to say the least, in embracing Pres. Isseyas as his security policy mentor. But the signal was clear, when, after signing the peace-cum-security pact between Addis Ababa and Asmara, the two men flew to Abu Dhabi to celebrate, and shunned the African Union summit that was held immediately thereafter.

Isseyas can declare innocence in the destruction of Ethiopia. He is discreetly silent while the country tears itself apart.

What is being destroyed is not just Ethiopia’s cohesion, but Ethiopia’s autonomy. It’s once-promising model of the developmental state in Africa is now history. The incoming Biden Administration will spend its time in office trying to manage the damage and won’t be able to pursue other goals. And the norms, principles and institutions of a multilateral African peace and security architecture will be trampled underfoot as well.

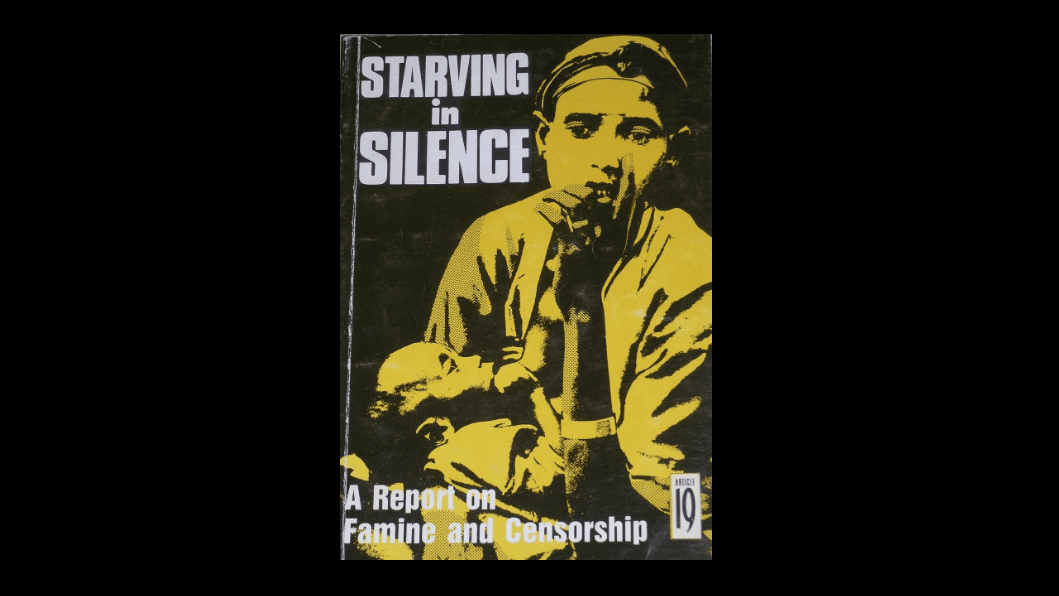

Photo: Chief Mass Communication Specialist Eric A. Clement, U.S. Navy March 05, 2007 Ethiopian National Defense Force 1st Lieutenant Ayella Gissa takes aim with an AK-47 assault rifle on a simulated enemy during a practical exercise as part of Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa’s train the trainer course in Hurso, Ethiopia, December 27, 2006. Public Domain