Between 1958 and 1961, the people of China suffered the greatest famine on record. Perhaps 36 million people perished. Astonishingly, this famine was concealed from the world and only became known more than 20 years later.

The Article 19 Report on famine and censorship, Starving in Silence, published in 1990, had one section on the great Chinese famine and one section on Ethiopia.

The comparison is relevant because on January 28, the Director General of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) awarded Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed the Agricola Medal, the organization’s most prestigious prize. Qu Dongyu is a Chinese agricultural expert who was nominated by his government to head the FAO.

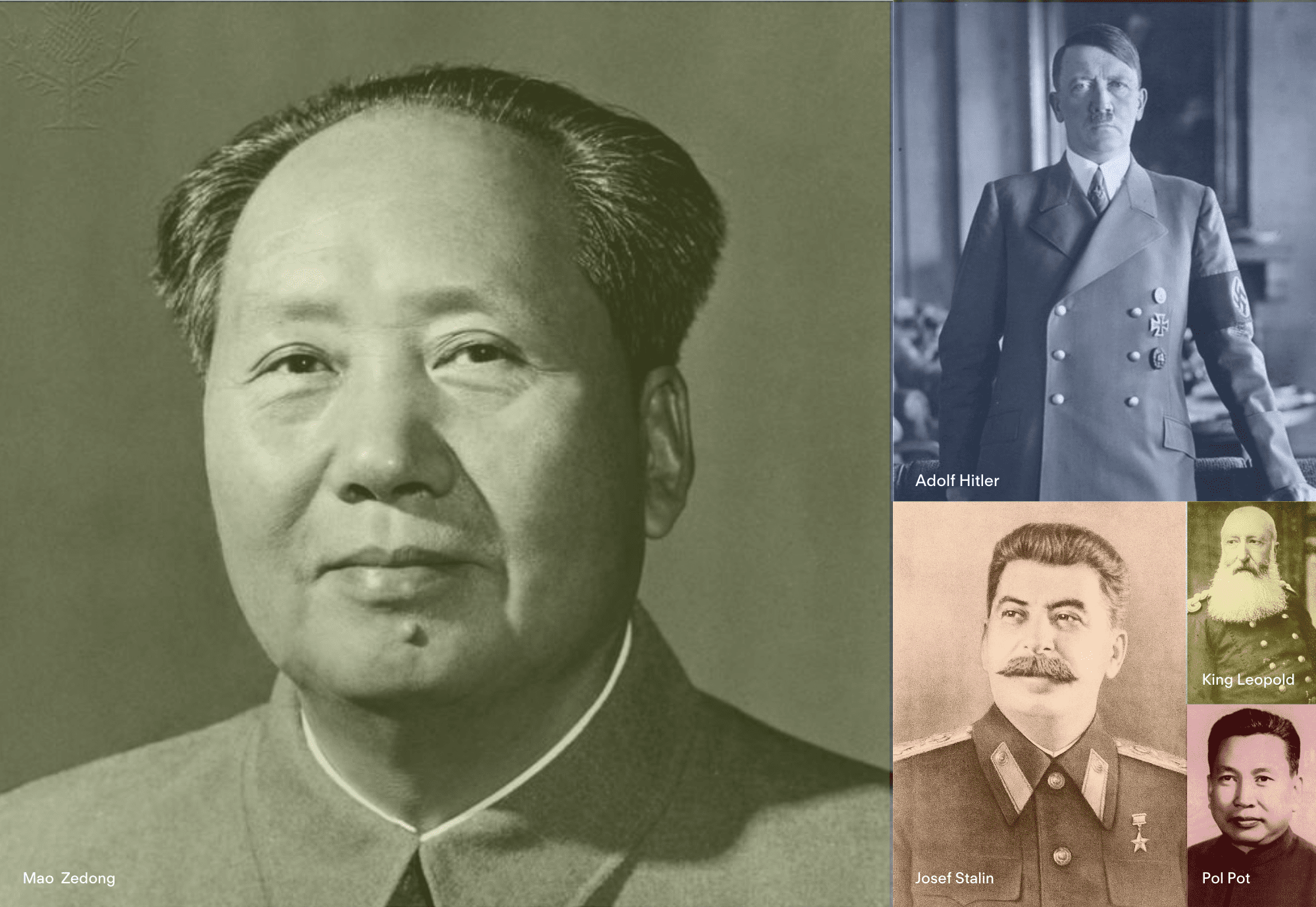

The cause of China’s famine was Mao Zedong’s ‘Great Leap Forward’, the fantastical scheme that promised to transform Communist China from a land of poverty to a beacon of prosperity. Mao announced that China’s revolutionary communal farming methods were producing vast surpluses of food, allowing the country to focus on surpassing industrialized countries in steel production.

It was a disaster. It was the single largest mass mortality event in one country of the 20th century.

Within months of the launch of the Great Leap Forward, reports began to come in from rural areas of peasants starving.

Chairman Mao wouldn’t hear them. In fact, he organized events to honor the cadres who had surpassed their wheat production quotas, handing out prizes to those who claimed the biggest harvests. National plans were made based on fanciful estimates made in Party headquarters, not actual data.

The following is from page 47 of Starving in Silence, entitled ‘Dizzy with Excess’.

Faced with food shortages, the bureaucracy refused to entertain the possibility that the food they had ‘estimated’ into existence still did not exist. The stubborn belief that the new communes could provide indefinite increases in yield became stubborn, implacable, and even a little unhinged. Mao, for example, had the following surreal conversation with Zhang Guozhong about a new commune in his province.

‘You have 310,000 people here in this county, and you’re just harvested 110,000 catties. How can you eat all that? What will you do with the surplus?’

Zhang was at a loss for words, perhaps because he was less at a loss for facts than the Chairman, but an accompanying cadre suggested trading it for machinery. Mao replied that with everyone producing so much grain, nobody would be willing to trade. Another cadre suggested making alcohol, and Mao replied that if everyone did that there would be too much alcohol. Receiving no reply, Mao laughed:

‘Actually, it is good to have too much grain. If the country doesn’t want it, if nobody wants it, eat it yourself. Eat five meals a day! Next year you can reduce the acreage, only work half the day, and spend the rest on study. Learn some science, study culture, and open a university or a high school…’

His interlocutors laughed. The conversation took place in August 1958, and yet by November, people in Henan were dying of starvation.

The vision of plenty spread by the leaders had undoubted popularity; Mao and agricultural chief Tan Zhenlin organized massive feasts to celebrate the good harvest.

The ‘Great Leap Forward’ was a leap into the abyss.

The historian and investigative reporter Yang Jisheng published his authoritative book, Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962, in 2008. He shone a light onto the real history of what had happened. His book is also full of stories of how Mao travelled the country celebrating the fantastical achievements of communist agriculture, even while peasants starved.

Yang won awards, but not in China—he was prevented from travelling to the U.S. to accept the Harvard Nieman fellows’ Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism.

Qu Dongyu hails from a rice-growing family in Yongzhou, Hunan, about 200 miles from Mao’s birthplace. According to figures reproduced by Yang (p. 395), there were 2.486 million ‘unnatural deaths’ in Hunan during the famine years. Qu Dongyu was born in 1963, a year after the famine finally receded. He studied horticultural science and rose to become Vice Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. He was elected as Director General of the FAO in 2019.

Last week, Qu Dongyu awarded Abiy Ahmed the Agricola Medal, the highest prize in his power to bestow. The FAO announced:

The Director-General highlighted that the Agricola Medal was being conferred to His Excellency the Prime Minister for his contribution to rural and economic development in Ethiopia, especially for his personal support to the Wheat for Food Self-Sufficiency programme, as well as Ethiopia’s Green Legacy Initiative that was in line with FAO’s Green Cities Initiative.

The Director-General further stated that he had witnessed the impressive development of Ethiopia over the past five years, which reflected the effective, accountable, and stable leadership provided by the Prime Minister, notwithstanding the difficult national, regional, and global challenges over the past years. The Director-General emphasized that this was an important message not only for Ethiopia, but for the African continent as well.

As outlined on this blog last week, Ethiopia is taking a great leap into a food security abyss. It is facing food crises and possible famine in Tigray and much of south-eastern Ethiopia. Even while the prime minister was announcing wheat exports to neighboring countries, aid donors were uncovering a massive and coordinated food aid theft that included diverting wheat to grinding mills to resell as flour. Even while the funds for essential food and medicine for the poorest cannot be found, Abiy is spending billions on a palace and on weapons.

Are Qu Dongyu and Abiy Ahmed dizzy with excess while peasants starve in silence?