Past world wars have been wars to establish world-spanning empires or wars among global rivals. While historic imperialism was mostly about conquering territory, today it’s more concerned with controlling the power to make money, and remake global institutions, law and ideology that legitimize global supremacy.

One battlefront in World War X is competition among kleptocrats. There’s a contest for position among political business entrepreneurs and CEOs. The Trump Administration wants to be the world’s top political business, for money and glory. Other geo-kleptocrats want to limit American power – they like this system overall, but don’t want to rank low in a world patronal hierarchy or neo-royalist system, and worry about whether a turbulent global political market will leave them precarious.

This makes for a new kind of a ‘new war’ – a joint enterprise in which the belligerents compete and collude. They all have an interest in kleptocratic impunity. But there can also be a clear winner – the world’s biggest political business.

There’s no doubt who is on top at the moment. Donald Trump took over a state with unmatched financial, economic and military muscle, and injected a new ingredient, the willingness to escalate against any rival on any front using any weapon, in a way that no-one else can match.

Others in the world system aren’t sure that America can sustain its dominance. There’s no alternative political business in sight with comparable money, weaponry and ambition – China runs a different kind of empire based on tightly regulated kleptocracy, President Vladimir Putin punches far above Russia’s economic weight but knows he can’t rival the big two, and Europe is only just finding some muscle but doesn’t conduct its political business in this way. Some are betting that Trump’s America will be a permanent fixture, either because they’re geo-kleptocratic true believers, or because they see this system crushing the alternatives. Probably, most politicians and businesspeople are hedging, trying to surf the current Trumpian wave but not wanting to be pulled under should it break.

Every political market operator knows that patronal systems go through massive disruption when there’s a power transition at the top. To put it another way, today’s White House court isn’t likely to last, and most of those paying their respects today are playing for time. Russia is one case, the Middle Eastern powers – Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – are others.

In the meantime, rivalries at different levels of the worldwide political market are making a whole series of existing wars – Sudan, Ukraine, Yemen to mention a few – intractable. These conflicts are stuck. The liberal multilateral mechanisms of the last thirty years aren’t working, but cutting deals according to the logic of the political marketplace only promises security pacts and short-term bargains, good while present market conditions prevail. Smaller powers are hoping that the multilateral institutions and international law – the old-style World Court – still has its role.

We can expect Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ to enter rentier political markets, with cash and coercion. Kleptocrats know the rules and may be ready to cut deals – which involve dramatic reshuffling of the political deck. But what we now from political marketplaces is that these bargains will last for just as long as political market conditions remain favorable, and will fall apart when they change. According to this logic, peace dealing is partly positioning oneself for the next round of warmaking.

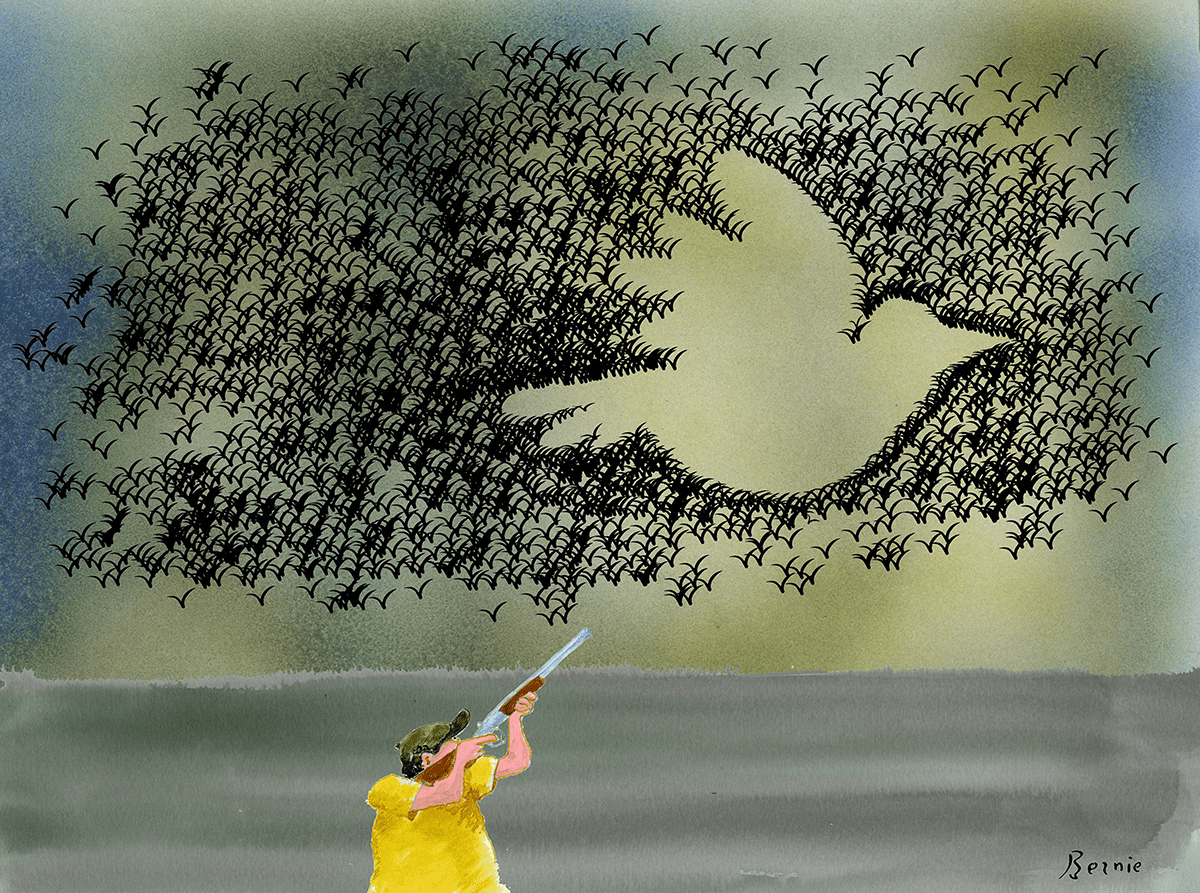

The second front in World War X is the battle to entrench the geo-kleptocratic world order itself. Geo-kleptocrats are fighting institutional-globalists over what will be the operating system for world politics. The kleptocratic political business model means that money and violence should trump law and institutions. In turn that demands waging a global culture war: kleptocrats need to discredit and destroy liberal multilateralism and to bring about an age of impunity.

But geo-kleptocrats need to be judicious in what they destroy, because despots, however powerful, cannot do away with laws and institutions altogether. A doctrine of exceptionalism only works when there’s a still a norm to be broken. A political business mogul needs to use financial, military, media and legal institutions to win against rivals and to avoid ending his life in disgrace. In the kleptocratic calculus, financial and military institutions count for more than civic ones, but all are relevant to some degree. Every autocrat has a lingering need for legitimacy, which is more than vanity, it’s also self-preservation. Just as warlords reinvent themselves as aristocrats and drug lords present themselves as philanthropists, geo-kleptocrats long for impunity – a craving that is the tribute that vice pays to virtue.

This is where the actual world court and world institutions matter. This is where international law and multilateralism – political and economic – count. This is the front where liberalism needs to regain its verve and values. Even if constitutional democracies can’t win universal support for their norms, they can retain the institutional frameworks, which over time will surely show their value – because they work.

There’s no doubt that the geo-kleptocrats are winning most battles today. Their liberal opponents are in disarray, divided over strategy and tactics. They don’t like brute power, and often lose tactical fights because they’re reluctant to stoop low, and aren’t good at street-brawl politics when they do. Democratic politicians can sometimes be bought cheaply. China – the other big actor in the global struggle – isn’t a liberal ally, it’s standing aside, preserving its own, and institutionalizing its own balance of business and politics. But liberals’ biggest problem is that they are entrapped in systems of finance and communication that serve them less and less well.

The third front in today’s war is the metatheory and the big prize of World War X – the power to make unlimited money. This is the fight for who controls the money-making technology of today and of the future. This is the truly transformative – and disruptive – empire-building element. At the moment this is driven by US tech giants, mega-businesses that want to run the world to expand their power and profit, that have America in their grip. In winning the Trump Administration’s license to charge ahead and build AI without regulation they have achieved a kind of political-economic singularity – the US has bet the house on this project.

But there are vulnerabilities in the US financial empire, notably debt and the question of how government and markets will handle the AI bubble. The Administration faces a strategic choice over whether to maintain the Washington’s legacy financial institutional architecture or to go for a major redesign that puts key financial decision-making under the control of the executive. That’s a decision that impacts the world, not just America.

America’s big competitor here is China, the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. Europe is seeking a way to use its economic and financial clout, its urgency accelerated by the Trump Administration’s bellicosity in trade wars. Meanwhile those in the Washington DC powerhouse can’t agree on how to handle their winnings. Will they heed the markets and play according to the rules – albeit revised – of global financial politics? Or will political finance and the lure of a kleptocratic power grab win the day?