Slavoj Žižek’s catchphrases are better known than his dialectics, and for good reason. His arguments on Ukraine, Israel, capitalism and world war are provocative but ultimately muddled. My review is sympathetic. I suggest that Žižek’s recent arguments, somewhat reconfigured, lead us to a counter-revolutionary synthesis, opening up the next agenda for emancipatory struggle.

Žižek published Too Late to Awaken: What lies ahead when there is no future? before Hamas’s attack into Israel, but his book has to be read with Gaza in mind. And since October 7, Žižek has tried to square his comparisons between Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu, his categorial support for Ukraine, and his demand that Hamas should be destroyed.

Žižek’s ongoing debate with himself is convoluted but provocative, infuriating and enlightening.

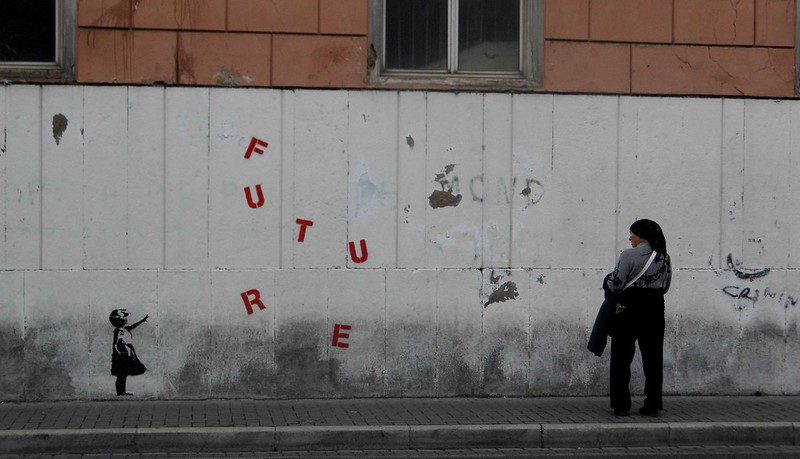

The ‘future’ in Žižek’s title is futur: what we expect in the normal course of events. According to Žižek, our futur is lost. If we carry on as we are, our civilization is doomed. Compellingly and memorably, he writes that we are not a few minutes before midnight, we are in reality after midnight.

The other sense of ‘future’ is avenir, something new that is to come—a radical break. For Žižek, the choice is between war causing revolution, or revolution before war. He writes that ‘in some basic sense the Third World War has already begun’, though it is currently fought by proxies, and fears a full war, which would be catastrophic.

What he misses—or at least doesn’t elaborate—is the economic faultline of a new worldwide war.

Žižek is a communist and historical materialism, interwoven with his insights into the cultural and ideological, frame his argument. He has taken a step on from his well-known aphorism that it is easier to imagine the end of the world, than the end of capitalism. In Too Late to Awaken, Žižek sketches what comes after the end of capitalism, which is corporate feudalism, in which giant companies control the public sphere which they drain of meaningful public politics. This is a system in which anarcho-capitalists not only coexist with conservative nationalists, but actually complement and feed off one another. There’s no contradiction between the ‘end of history’ and the ‘clash of civilizations.’ This is (to elaborate on Žižek’s argument) the internal dialectics of capitalist counter-revolution working themselves out.

The advocates of revolutionary politics, meanwhile, are reduced to melancholic apathy, their ‘pseudo activity’ taking the place of the political work of the revolution. Žižek is scathing in his critique of the ‘local stupidities’ of the ‘Left’ (scare quotes are his) that is more concerned with ideological purity than material change, making enemies out of its potential allies in a broad coalition for progressive change. As public ethical standards are reduced to subjectivities and positionalities, the criminal right that celebrates its transgressions cannot, at least, be accused of hypocrisy.

Žižek takes a categorical position against Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. For him, the minor wrongs, such as the provocations of NATO expansion and profiteering from arms supplies, are overshadowed by the big evil, which is Russia’s project of reconstituting empire at the expense of democratic, self-determining Ukraine. Žižek has no truck with the kinds of territorial or political concessions that might allow Putin to save face; this would not, he says, be a meaningful peace. In fact, he goes further, writing that Ukraine is ‘provoking Russia’s imperial ambitions by resisting even when the situation is desperate. Today, not provoking Russia means surrender.’

Žižek draws on the distinction between principal and secondary contradictions, articulated by Mao Zedong, who was assessing whether the Chinese Communist Party should be resisting foreign occupation or waging class war. It’s a Hegelian framing that appeals to Žižek.

But the assessment depends on what the Marxist-Leninists would call a ‘correct’ reading of geopolitics. The political work of liberation requires judgement about what is possible, and what demands compromise. When Žižek was writing, it was not widely reported that the United States and Britain shut down potential peace talks in the early months after the Russian attack. As it becomes clear that major western powers wanted a war that would bleed Russia—and may have miscalculated—we must ask if Ukrainians are being sacrificed in a conflict that is not wholly their own.

And Žižek also misses the brute fact that, underneath Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s theatrics lies a kleptocratic Ukrainian state, still unreformed. European-democratic rhetoric is twinned with corporate feudalism.

The book was completed before Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7 and the full-scale assault on Gaza that followed.

Before October, Žižek compared Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory and its refusal to recognize the Palestinian state, with Vladimir Putin’s belief that Ukraine and Ukrainians have no historic right. He likened the Russian and Israeli formulations of peace as pacification. In a column for Project Syndicate on March 1, 2023, he wrote, ‘To condemn Russian colonialism properly, one must be consistent and also condemn other examples, not least Israel’s subjugation of Palestinians in the occupied territories.’ He added, for good measure, ‘The Western media is full of praise for Ukraine’s “heroic resistance,” but mute on the issue of West Bank Palestinians who resist a regime that is becoming ever more comparable to South Africa’s defunct apartheid system.’

A few days after October 7, Žižek wrote another Project Syndicate column in which he unconditionally condemned Hamas’s attack and affirmed Israel’s right to self-defense, writing that ‘Hamas and Israeli hardliners are two sides of the same coin.’ In his view, Hamas is not a progressive liberation front in either theory or practice. In fact, he says it should be destroyed.

When he has spoken publicly on the Gaza war, Žižek has been heckled, by both sides, his debate with himself condemned as inconsistency or hypocrisy. This speaks to the near impossibility of saying anything about the Israel-Gaza war that isn’t trivialized.

Nonetheless we could hope for something more substantive about how the liberal peace lies under the rubble of Gaza no less than in the ruins of Mariopol, and how the futur is arriving faster. Are Netanyahu’s war aims not nihilistic? Is there not a collusion among purportedly hostile powers that a great war is preferable to a revolution? Is the exchange of fire between US warships and Yemen’s Houthis not bringing us to within a second of a full-scale war?

The Israeli war of annihilation on Gaza supports Žižek’s thesis that the Third World War is already underway, waged by proxies. The symmetrical hypocrisies of the world powers, and their imperial logics, are on full display.

I think that Žižek has got lost here, and a signal of this is his invocation of ‘war communism’—emergency economic and political measures that ‘will have to violate not only the usual market rules but also the established rules of democracy.’

War communism doesn’t have an encouraging record. In fact, even more than proxy conflicts, the emergent world war is an economic contest. Like the war economies of the last eleven decades—communist, state capitalist or America’s ‘credit card wars’—these shift the burden of paying for warmaking, and almost always it is the poorest at home and the most vulnerable in the colonized world who suffer as a result.

Writing for Haaretz, Žižek may have stumbled upon how to resolve his dialectic. He remarked that, ‘If Trump wins, the United States will simply become one of the BRICS members, who, for what they call a true multicentric world, will peacefully put up with each other’s crimes.’ (‘Peacefully’ properly belongs in scare quotes.) If true, it’s a world counter-revolution that may prevent, or more correctly reconfigure, World War Three. Ukraine and Gaza, however significant they may be, may just be secondary contradictions in the shadow of this principal one.