Famines are complicated, and their causes can be obscure and confusing. Examining the historical record confirms this.

Each famine is a destructive and complex crisis, driven by one or more of conflict, climate change, and economic crisis. Each is embedded in its particular historical context. To better understand the drivers and triggers of famines, we examined the World Peace Foundation dataset of 83 major famines—each with over 100,000 deaths—spanning 1870 to 2022. Each famine in the dataset is coded according to the causes identified in the academic literature on that particular episode, categorized into immediate, contributing, and structural factors.

This analysis integrates and standardizes all the causes cited in the dataset. Two methods were applied: (1) medium-level categorization, which groups similar phrases into up to three categories per cause, and (2) semi-structured grouping for immediate causes, employing ‘fuzzy logic’ to generate 123 semi-structured labels and 28 standardized categories. This approach enables a deeper examination of recurring patterns and systemic dynamics that have historically precipitated famines.

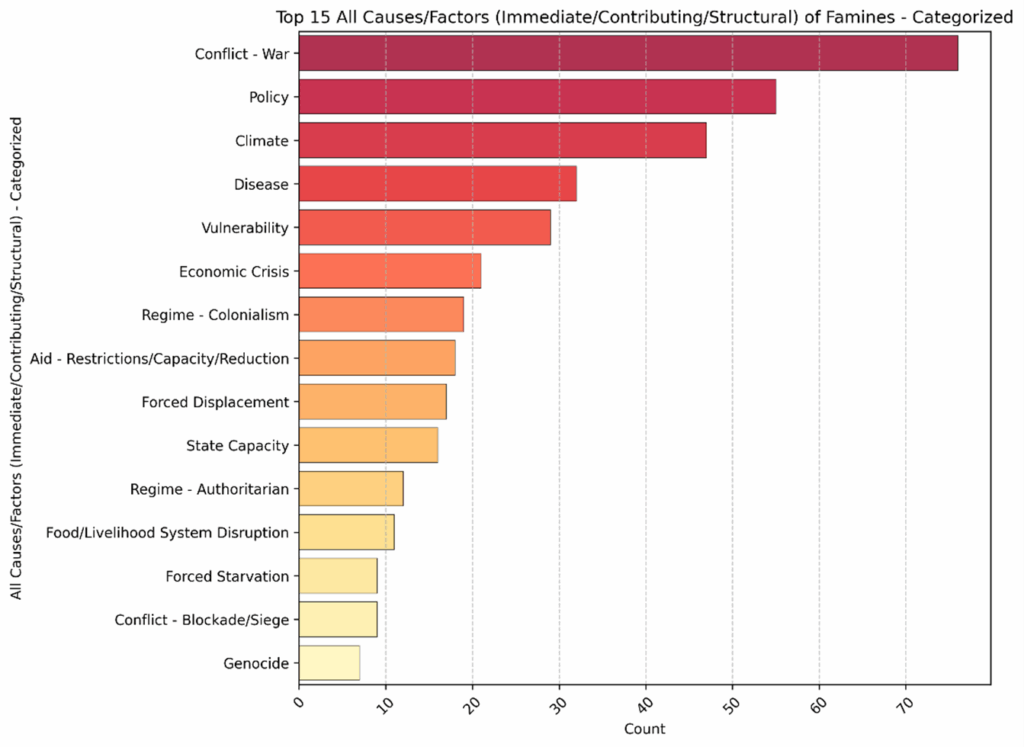

Top 15 Famine Causes/Factors – Categorized

Analyzing all the categorized drivers and triggers of famine reveals three broad frequency-based bins. The first bin (30 or more mentions) highlights conflict, policy, climate, and disease as the most prominent features of historic famines. War disrupts livelihoods and access to food; policy decisions—such as wartime provisioning, heavy taxation and collectivization—exacerbate scarcity; climatic events like droughts and floods afflict agricultural production; and disease amplifies mortality.

The second bin (15–30 mentions) includes vulnerability, economic crises, regime (e.g., colonialism), aid restrictions, and displacement. The third bin (1–14 mentions) comprises diverse contributors: state capacity, authoritarian governance, livelihood disruptions, forced starvation, and siege tactics.

Figure 1: Top 15 Causes\Factors of Famine – Categorized

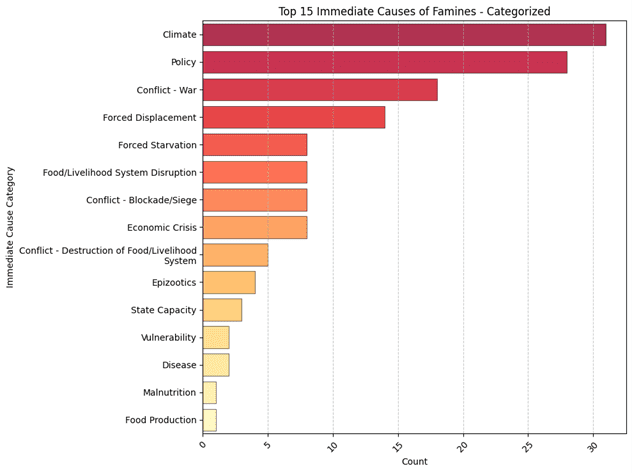

Top 15 Immediate Causes – Categorized

Understanding famine requires not only grasping its structural or underlying drivers but also identifying the proximate triggers that precipitate its onset. Climate shock(s), policy, and conflict (war) are most common—and not surprising. Notably, while food system disruptions are central to famine dynamics, they are less often identified as immediate triggers, underscoring the diverse pathways that can culminate in mass starvation, destitution and death.

Figure 2: Top 15 Immediate Causes of Famine – Categorized

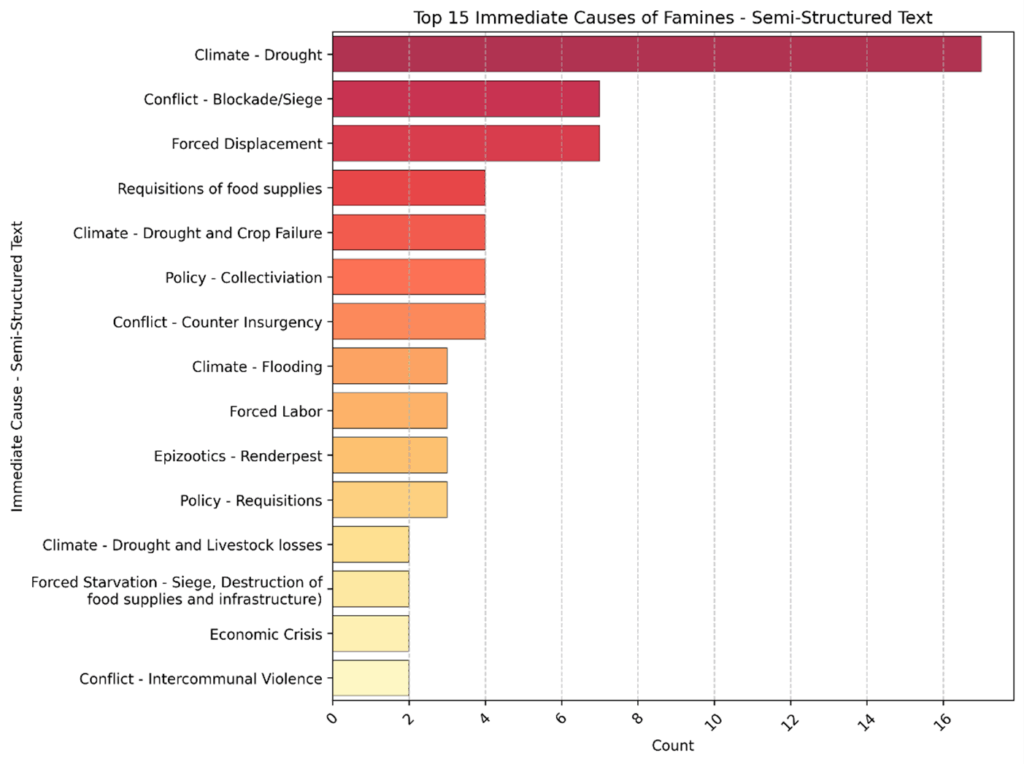

Interestingly, despite our efforts to standardize the categories, there are still numerous unique semi-structured label entries. In total, there are 127 unique semi-standardized categories, each shedding light on the complex and varied nature of famine triggers. This diversity suggests that while certain high-level fundamentals are consistently significant, the specific famine triggers vary widely. For example, the 8-11 most frequent labels are only mentioned three times each.

Figure 3: Top 15 Immediate Causes of Famines – Semi-Structured Text

Key Takeaways

Across all causes and factors, the frequency of categories aligns with expectations. Conflict – particularly war – is the dominant feature linking great famines across time, but in very uneven ways. Similarly, state policies, whether through various forms of taxation, collectivization of agriculture, or deliberate infliction of starvation and destitution, are important. Climate shocks also feature prominently across a large portion of famines, especially in the earlier period of the dataset. Interestingly, although not surprising, disease and vulnerability are the fourth and fifth most mentioned features of famine, respectively, ranking higher than economic/market factors and food/livelihood disruptions.

At the category level, the top immediate causes of famine also align with expectations: climate, state policy, and conflict/war. However, there are interesting insights in the middle ground, with instances of forced displacement, forced starvation, conflict-related blockades or sieges being mentioned at similar levels to food/livelihood system disruptions and economic crises, including market and price issues.

Lastly, while semi-structured labels provide insights into the nuances of immediate causes, allowing for some cross-comparison, few well-defined groupings emerge. The clearest one is drought. For the man-made causes, that are overall more common, there is far more diversity.

Overall, this analysis highlights two key insights. On one level, the facets of what builds the foundation of famine remain similar across time and space, aligning with our general understanding. On the other hand, it isn’t as simple as it looks. When examining immediate triggers (the straw that broke the camel’s back), these can vary greatly across famines. While we can be certain that a devastating war, extreme weather events, and disastrous (and sometimes deliberate) policies open the curtains to the potential of famine, the final acts that ultimately result in starvation, destitution, and mass mortality are not always simple.

In summary, it can appear easy spot the fundamentals of famine, but predicting the exact pathway towards it remains uncertain – and that may always be the case.