Israel’s use of food and hunger in Gaza today has echoes from handbooks for colonial war and counterinsurgency doctrines. This is one way to think of the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation—an experiment in food control counterinsurgency for the digital era.

But it has its limits. Rationing as an instrument of control can, at the end of the day, only be enforced by bullets.

Between 1948 and 1960 the British colonial government in Malaya fought a war against the Malayan National Liberation Army, a communist guerilla force. Britain called it an ‘emergency’ and Sir Robert Thompson, one of its commanders, wrote the campaign up as a success. It was hailed as a model by the US for operations in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq and cited in the 2006 US Army field manual for counterinsurgency.

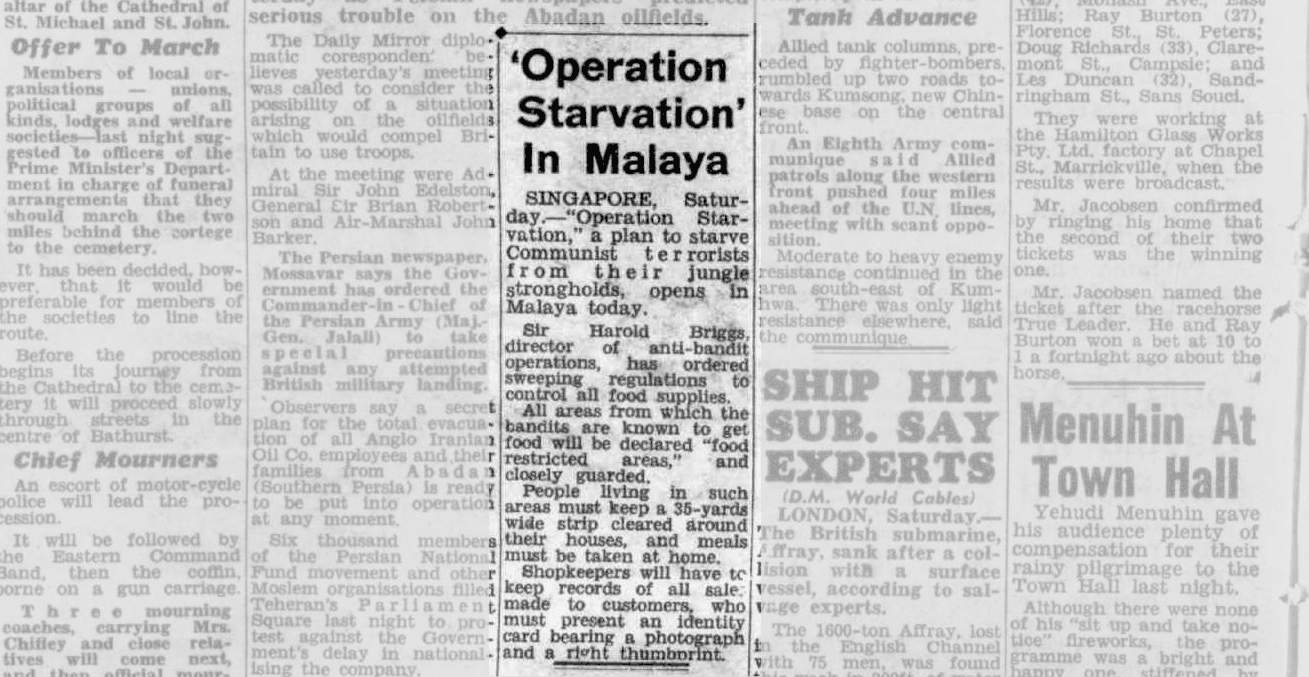

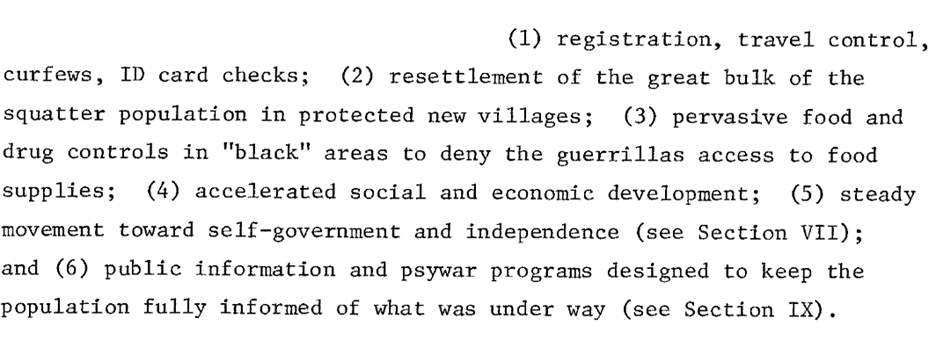

Control over food was central to the war strategy. In 1951, Sir Harold Briggs, director of ‘anti-bandit operations’, launched what he called ‘Operation Starvation.’ (Later the British just called it the ‘Briggs Plan’.) It is described in detail in a 1971 RAND Corporation analysis, which summarized the ‘civil programme’:

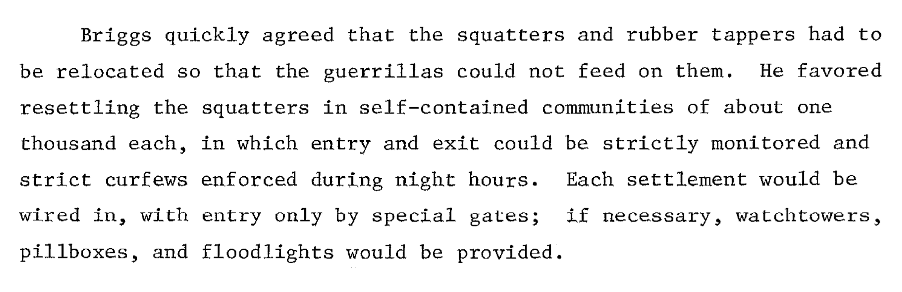

The plan required complete physical separation of the civilian population and the insurgents, using barbed wire and free fire zones.

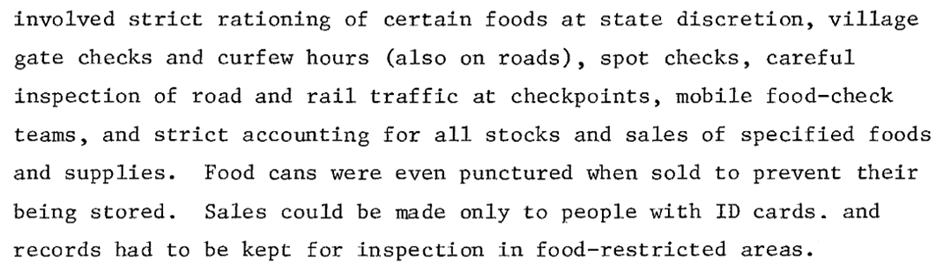

Sometimes control over food extended to running communal kitchens, because cooked food couldn’t be stored for the guerrillas to use. More widely the plan:

The people hated it. Malaysian historian Gary Lit Ying Loong said it was “probably the biggest relocation exercise at the time, with about 600,000 people being moved into these new villages, or concentration camps.” We should note that the British invented the concentration camp during the Boer War in South Africa in 1900-02, also as a means of weaponizing access to food, so the term is used in that context, not Nazi extermination camps.

In the following extract, ‘GOM’ refers to the British-run Government of Malaya. Riley Sunderland is the author of an earlier report for the RAND Corporation on the operation.

Unreported at the time, the insurgent areas were also sprayed with the herbicide Agent Orange, a weapon later used on a larger scale by the US in Vietnam. The index used to measure the success of food denial was the number of ‘surrendered enemy personnel’ or SEPs.

How does the experience of Malaya transfer to the operating model of the Israeli Defense Force and the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation?

- The tactical goal is the same: to separate the insurgents from the civilian population, starve the insurgents and provide rations to the civilians in a way that means that they can’t feed the insurgents.

- The Malayan operations were carried out in a jungle setting; Gaza is an urban environment. So physical separation—the ‘protected village’ or ‘concentration camp’—is far more difficult in Gaza. But there are new technologies that have allowed Israeli military planners to think more ambitiously. In Afghanistan and Iraq, the US developed the digital weaponry for ‘identity dominance’, or biometric war. Israel has taken this to a new level with its ‘Lavender’ AI machine for targeting individuals suspected to be Hamas militants. As a corollary of this, the GHF method can be seen as creating a ‘digital concentration camp’ that combines surveillance humanitarianism for those deemed eligible with individually targeted starvation for those not.

- The British operation was much crueller than was admitted at the time. The idea of ‘hearts and minds’ counterinsurgency has been shown to be largely a myth. Thompson’s celebrated account of Malaya is, according to Douglas Porch, “a didactic, aspirational treatise rather than as a statement of fact.” The Malayan emergency still awaits an exposé akin to the contemporaneous ‘emergency’ in Kenya that belatedly led to a lawsuit brought by survivors to the British High Court.

- There’s no evidence that Operation Starvation actually starved Malayan civilians to the point of significant deaths related to malnutrition. But the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation plan doesn’t provide enough food to enough people, or the full spectrum of essential services including water, sanitation, electricity, health care, and specialized care for malnourished children, to prevent a descent into mass starvation.

- Denying food to insurgents in Malaya proved difficult, extremely slow, and had uncertain results. The British needed to set up bases in the jungle to ‘protect’ the aboriginal communities living there, and there is no record for the deprivation suffered by those people. The reality is that armed men invariably starve last. The numbers of insurgents who gave up because of hunger increased as the years wore on—but was still a small proportion overall.

- The Malayan emergency occurred at a time when international humanitarian law was very permissive towards starvation crimes. That’s no longer the case, and for good reason.

- Israel’s strategic goal in Gaza is very different. The Malayan repression gained some legitimacy because Britain conceded Malayan nationalists’ main goal—independence. The government of Israel shows no indication that it is considering anything comparable. Until such time as it does so, counterinsurgency is an endless exercise in ‘mowing the grass’—killing each crop of militants as they grow up. This is, as RAND Corporation analyst Raphael Cohen writes, born of “strategic fatalism … [and] a large measure of hubris” destined for “inevitable, ongoing failure.”

The Gaza starvation experiment can be enforced only at the point of gun.