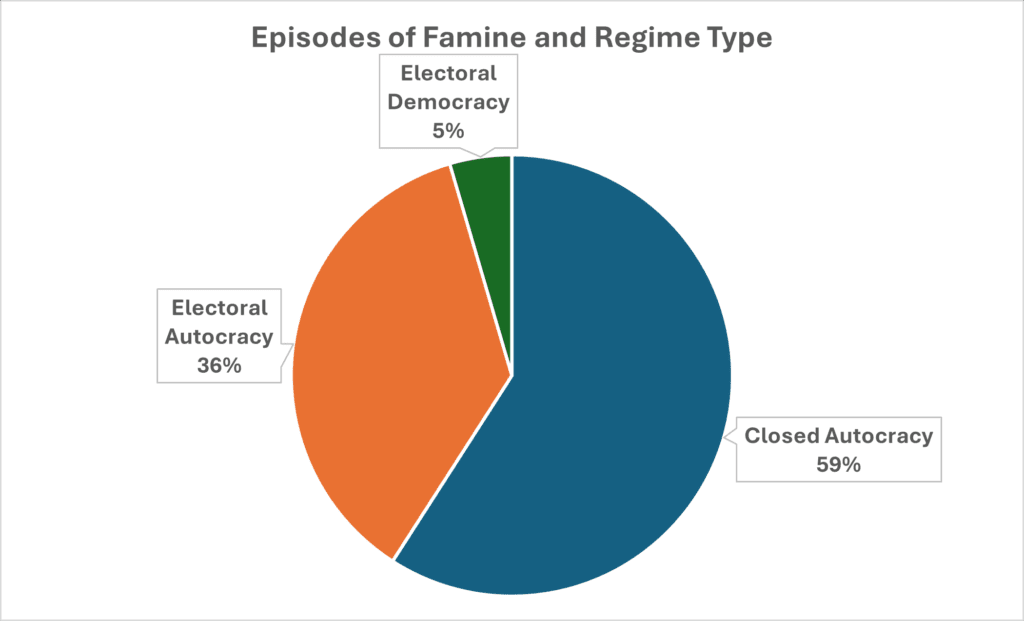

The numbers are stark. In the analysis of 22 famine events across post-colonial Africa, 59% occurred under closed autocracies, 36% under electoral autocracies, and just 4.5% under electoral democracies. Zero famines have struck liberal democracies. This isn’t coincidence—it’s evidence of Amartya Sen’s insight that democratic accountability helps prevent famines.

As Sudan faces potential famine with millions at risk, understanding why some political systems help prevent mass starvation while others enable it has a renewed urgency. The research across Africa’s 54 countries, covering approximately 2,500 country-years since independence, reveals that regime type fundamentally shapes whether people live or die during food crises.

Testing Sen’s theory with African data

Sen’s famous claim that “no famine has ever taken place in a functioning democracy” has shaped development thinking for decades. His entitlement theory, which at its core is an economic theory, can be used to explain why: famines occur not because food disappears, but because people lose their ability to acquire it.

Democratic institutions prevent this through three mechanisms: free press provides early warning, competitive elections make leaders accountable for preventing disasters, and civil society mobilizes resources and pressure.

To test this theory, the paper analyzed every major famine and severe food insecurity event (IPC Phase 4 or 5) in post-colonial Africa, using the Varieties of Democracy project’s classification system. Rather than simply categorizing countries as “democratic” or “authoritarian,” this approach recognizes four regime types: closed autocracies (no meaningful elections), electoral autocracies (unfree elections), electoral democracies (competitive elections but weaker institutions), and liberal democracies (full democratic institutions with rule of law).

The results strongly support Sen’s thesis, with important nuances. Thirteen famines (59%) occurred under closed autocracies like Ethiopia under the Derg military regime, which suppressed information about the 1984-85 disaster that killed over 600,000 people. Eight famines (36%) struck electoral autocracies, countries with elections but limited freedom. Just one famine occurred in an electoral democracy: Nigeria’s 2016 northeastern crisis during the Boko Haram insurgency.

War, exceptions, and autocratic successes

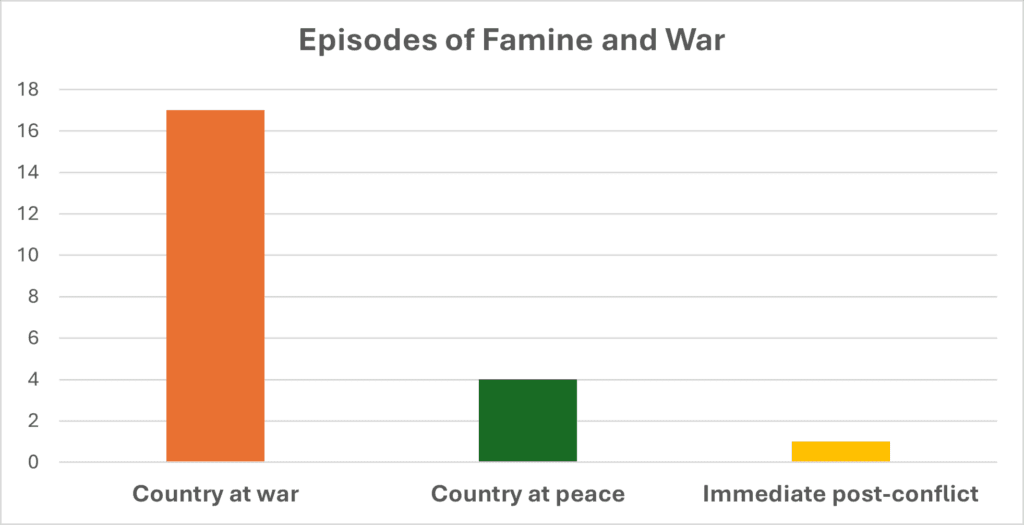

The Nigeria case reveals democracy’s limits. Boko Haram’s systematic destruction of food systems and aid blockades created famine conditions despite Nigeria’s democratic institutions. The crisis exposed critical weaknesses in these institutions: press freedom was severely restricted with journalists facing threats and military-controlled access, civil society operated under significant constraints, and the politically marginalized populations of northeastern Nigeria, particularly ethnic minorities like the Kanuri and Fulani, lacked effective representation in federal decision-making. The delayed response that led to thousands of preventable deaths illustrates how formal democratic structures can fail when some citizens are effectively excluded from the political community.

This shows that war complicates the picture significantly. Seventeen of the 22 famines occurred during conflicts, when normal governance breaks down. Yet regime type still matters: democratic institutions provide correction mechanisms that autocracies lack.

The trend toward democratic protection

While democracy doesn’t guarantee famine prevention, Nigeria’s experience proves that, the trend is unmistakable. Moving from closed autocracy to electoral autocracy reduces famine probability. Moving from electoral autocracy to electoral democracy reduces it further. Liberal democracies maintain perfect prevention records.

This matters urgently for contemporary Africa. Military coups in Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso, and elsewhere haven’t just threatened democratic values, they’ve weakened institutional mechanisms that prevent mass starvation. Sudan’s trajectory from electoral autocracy to military rule to devastating war shows how political breakdown creates humanitarian catastrophe.

The research findings answer the research question clearly: democracy is not sufficient to prevent famines in post-colonial Africa, as Nigeria’s case demonstrates. However, the data shows that democracy significantly reduces famine risk and provides crucial correction mechanisms when crises occur.

Sen’s theory retains explanatory power while acknowledging its limits. Democracy doesn’t automatically prevent humanitarian disasters, especially in fragile states facing insurgencies. But the evidence strongly supports prioritizing democratic institutions as famine prevention mechanisms. More democratic governance means fewer people starve during the next drought, conflict, or economic shock. That relationship is worth defending with both moral conviction and hard data.

—