This is the fourth blog in my ‘World War X’ series, in which I turn to the commodity theory of power—the operating system of transactional politics. Power is the world’s most valuable commodity. But the trade is illicit—it’s a crypto-commodity.

From classical times if not before, power has been bought and sold. In 193 AD the Praetorian Guard of the Roman Empire held an auction, with the man who offered them the most—Didius Julianus—carried aloft by the guardsmen to serve as emperor (for a short while, until they deposed him). Princes and parliamentarians are susceptible to bribery. Wealthy rulers use money to hire mercenaries and win allies.

These kinds of transactions don’t make power into a commodity. They are one-off events and barters. To be a market, the laws of supply and demand need to be at work, so that prices for political office, allegiances and services move accordingly.

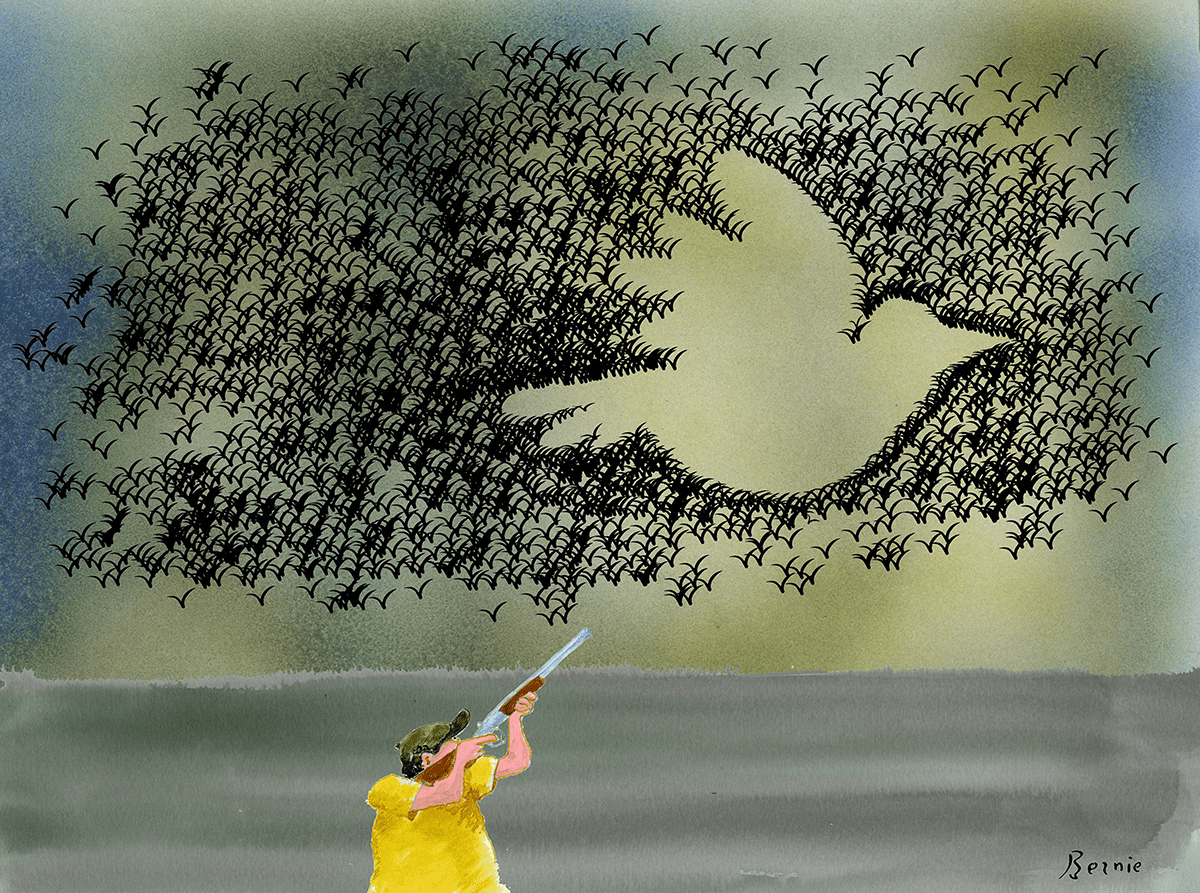

Rather than a standard commodity, power is a ‘fictitious commodity’—produced through processes other than the market and always subject to demands that it be treated differently. Also, power is not traded openly in a transparent market where prices and trades can be tracked by the public—but the dealers and their political consultants know exactly how it works and what is the right price for each transaction. They just don’t want the public to know. That’s why I call it a ‘cryptocommodity.’

The market in power is priced in US dollars—and cryptocurrencies.

How did this happen? Historically, the key innovation was the armed trading company, authorized to wage private wars and negotiate on an equal basis with sovereigns, that could also buy enough influence in its host state to become ‘too big to fail’—a pillar of the constitution of empire. That’s the British East India Company in 1800. Its portfolio included hundreds of lawmakers in Westminster, standing armies and warships, principalities from the Persian Gulf to the Bay of Bengal, and the Mughal empire. It sliced and diced sovereignty and traded in it, just as it bought and sold tea and opium.

That logic of mercantile empire never went away—it just faded into the background for 150 years. It’s back now.

Kleptocracy flourished in the spaces where Communism collapsed, notably Russia in the 1990s. In 2000, President Vladimir Putin tamed the oligarchs—becoming the monopolist in the country’s political market. Russian foreign policy is marked by the efficient deployment of these skills in Middle Eastern and African countries, where organized crime also emerged from the belly of the state.

Both Iran and Israel use political money. Iran mobilized proxies using payouts as much as sectarian affinities, contributing to the descent of Iraq, Lebanon and Syria into violent political markets. Gaza’s Yasser Abu-Shabab is emblematic of the kind of politically-skilled gangsters who thrive in such an environment. Egypt’s Ibrahim al-Organi is another.

And it should be no surprise that the most accomplished practitioners of this style of politics are found in a polity which was set up and run on this basis two centuries ago and has an unbroken history of rule by the same sovereign families ever since—the United Arab Emirates.

How does it work? The practice adjusts to the circumstance while the logic remains the same. Politicians intuitively understand the practice, though as a general rule, academics find it distasteful.

The system is run by those who have the political money to spend. In an authoritarian system, the ruler monopolizes rewards and penalties. It’s the job of his intelligence officers and party bosses to figure out who to buy and for how much. Then, they can set up a pseudo-democracy.

Where there are genuinely competitive elections, the men in charge (and yes, everywhere it’s a male-dominated business) need to figure out the rules of the club. Nigeria’s ‘godfathers’ have configured a system that is so expensive that every candidate needs a wealthy paymaster. This debars anyone but their chosen clients from running—the voters may have a choice, but only from the chef’s menu. And running for office costs so much that the winner is accountable to his godfather, not the voters.

To fight a war, a ruler’s first task is figuring out the terrain of the market in men with arms. He needs to pay for weapons, logistics, soldiers’ salaries—but victory comes when he is the chief buyer in the market of loyalties.

The ruler is the one who has a monopoly over power—in the economist’s sense of having a dominant market share to the extent of being able to set prices and prevent others from entering the market. Effective monopoly requires control over law, communications and, most importantly, force.

The monopolist can accumulate more power, both through a dominant market position—buying more—and also by tightening the regulation of the market using law, communications and force. Often, it’s an oligopoly of big men, who may collude or conspire against each other.

Surviving in this system—let alone thriving—requires not just money but acumen. A political business manager has an encyclopaedic who’s who of people, how they relate to one another, and the capacity to calculate all manner of contingencies, thinking two or three steps ahead, and knowing the biases and limitations of those who are feeding him market intelligence.

What does mean for democracy, corruption, and sovereignty? Our public political language is all about policy, institutions, and order. But among themselves, politicians talk about money and relationships.

We shouldn’t think of corruption as individual agents cheating an honest state, but as the pervasive symptom of the underlying condition. The beating heart of kleptocracy isn’t getting rich but the trade in power. Personal enrichment is a big part of the system, but the money that counts is the money that’s circulated back into politics.

We shouldn’t think just about a contest between authoritarianism and democracy—the key is who gets to dominate and regulate the market in power. When an autocracy falls, democrats rejoice, but it’s those who can put money behind political entrepreneurs in the newly-deregulated marketplace who will win the day.

And in international relations, sovereignty is subordinate to the price calculation. Some government leaders see the opportunities for renting out their services (territorial, military—or as a legal cover for criminality) for personal and political profit.

Because power is unevenly commodified across the world, in some places it’s cheaper to buy, or easier to steal, than in others. Outsiders don’t venture into the Nigerian political market as it’s expensive and any operator needs a lot of local political intelligence to deal.

In other countries it’s easier and cheaper—European democracies are a case in point, ripe for hostile takeover.

In the United States, there’s a fierce contest over how to regulate the political market. The Republican and Democratic party establishments agree that the price for entry into the market should be high and that low-budget campaigns should be deterred.

The first into the market can accumulate power by theft or guile, outsmarting those naifs who think that they possess something that is beyond price. Citizens who believe that power is regulated by law and custom according to the sovereignty of the people will discover only too late that they have been tricked out of their national birthright.

Geo-kleptocracy is the global market in power. World War X is the fight over whether the oligopolists collude or compete, and whether a single monopolist can win. Money is both the principal means used in the contest, and the power to make money is the biggest prize—the next entry in this series.