This blog post draws on some of the issues highlighted in the report, Defining the Crisis in the Sudans: Lessons from the African Union High-Level Panels for Sudan and South Sudan, by Alex de Waal and Abdul Mohammed, published by the Thabo Mbeki Foundation and the World Peace Foundation, with the support of the United States Institute of Peace.

‘The first duty of the mediator is to define the problem.’ Fifteen years ago, presenting the report of the African Union High-Level Panel on Darfur to the AU Peace and Security Council, the Panel’s chairperson Thabo Mbeki spoke these words. The report he presented defined ‘Sudan’s conflict in Darfur,’ that could be resolved only by national-level democratization that enabled the people of Darfur to participate fully in the affairs of the Sudanese nation.

When the Panel was first established, President Mbeki’s first question was, ‘what do the people of Darfur have to say about the conflict?’ On hearing that they had not been asked, he insisted on consulting them. The AUPD report was based on forty days of town-hall style consultations with people from all walks of life and all political persuasions in Darfur, and in Khartoum.

The Panel was re-mandated as the AU High-Level Implementation Panel for Sudan. The AUHIP was tasked with supporting the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, then a partner in government in the united Sudan, in implementing the remaining provisions of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, in the context of the national democratization of Sudan.

With the other two members of the AUHIP, General Abdelsalami Abubakar (Nigeria) and President Pierre Buyoya (Burundi), Mbeki added two other definitions to Sudan’s crisis.

He insisted that when South Sudan seceded from Sudan, the result would be two African states, each characterized by ethnic and religious diversity.

Some in the north rejected this, arguing that South Sudan was a state for Africans, and northern Sudan was a state for Arab-Muslims. Hardline Islamists’ rejection of a framework agreement that would have ended conflict in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile within weeks of it breaking out in June 2011, was the original sin of post-secession Sudan, setting it down the road to war, isolation, economic collapse and state failure.

As the secession of South Sudan approached, the AUHIP also facilitated agreement between north and south that the overriding principle should be ‘two viable states’—democratic, developmental, at peace internally and with one another. Although the GoS and SPLM accepted this principle, each sought tactical advantage over the other, leading to a tit-for-tat escalation that led to the point of war in April 2012, barely nine months after the independence of the South.

That war was resolved by the operation of Africa’s peace and security architecture. The AU, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD, the northeast African regional bloc), the League of Arab States, and the United Nations all came swiftly into alignment on a common position on stopping the war and adopting a roadmap to resolve all outstanding disputes between South Sudan and Sudan. At a time when the UN Security Council was paralyzed by the division between the US and Russia over Syria, the AU—with the Panel in the lead—was able to obtain a unanimous vote in support of a Security Council resolution endorsing its plan.

The role of the US, through its Special Envoy Princeton Lyman and then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is worth noting. Lyman was able to use the common position of the multilateral agencies to get China and other states onside. And Clinton was in regular contact, reading weekly briefings and intervening directly at the highest level when needed.

It was precisely the same multilateral alignment, and close cooperation between the multilateral organizations and Washington DC at the highest level, that made it possible for peacekeepers to be deployed to Abyei, despite very serious reservations by the GoS. The blue helmets in Abyei are the only international peacekeepers still stationed in Sudan. Neither the UN, the AU, the Arab League nor the US seems to have the diplomatic tools, nor the political will, to replicate that exercise at a time when it is even more desperately needed.

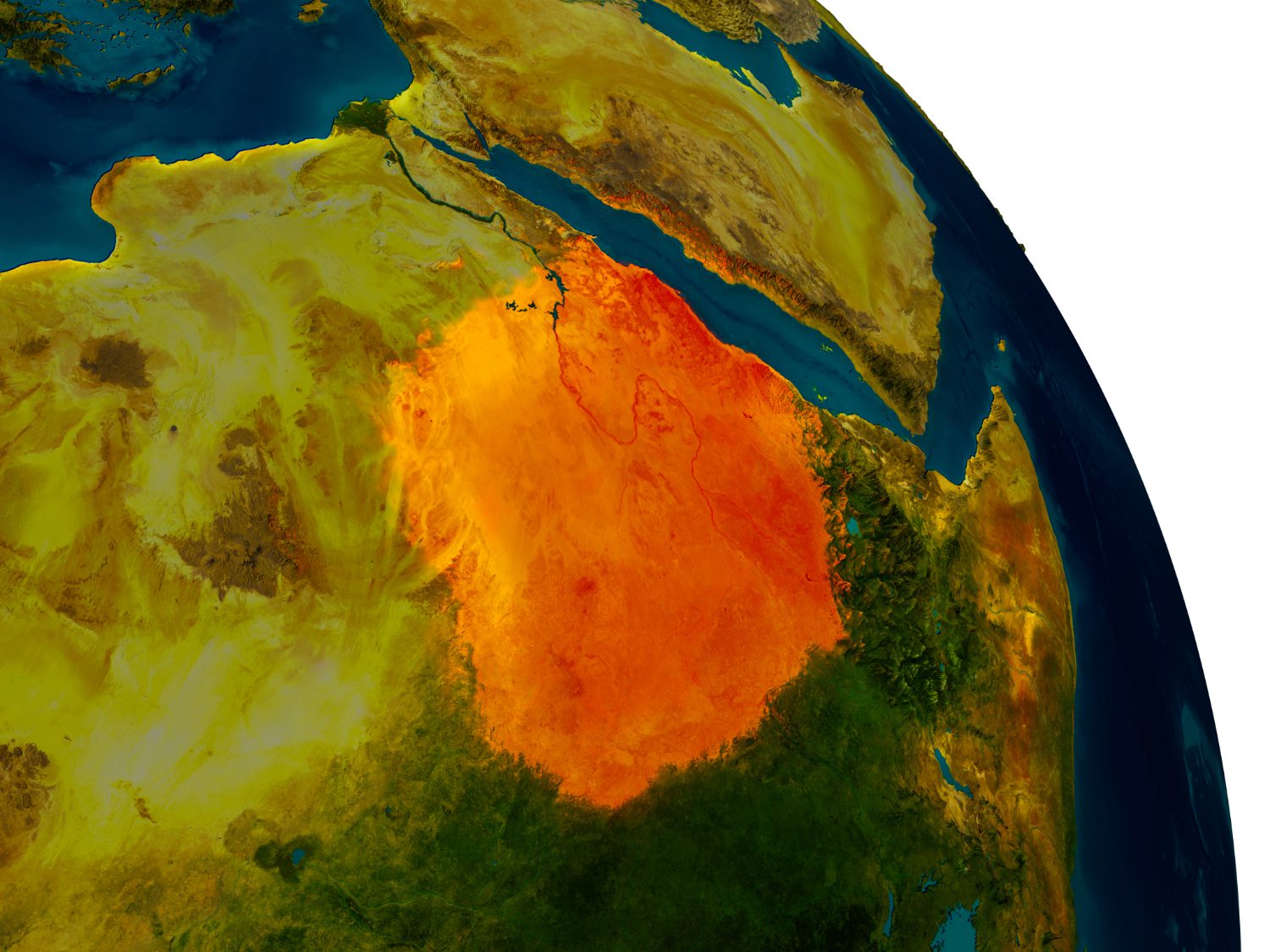

Subsequently, at a 2017 conference on peace and security in the Horn of Africa, President Mbeki added another definition to the crises in the Sudans: the position of the two countries in the geo-strategic politics of the Red Sea Arena. In the mid-2010s, the assertive security strategies of the middle powers of the Middle East had introduced a new element to the challenges of the two countries. Instead of the work-in-progress of the African peace and security architecture, the crucial mechanisms for peace and security were now in the hands of rivalrous powers, most non-African, which had little regard for the norms, principles and institutions of multilateral peacemaking.

The term ‘Red Sea Arena’, first introduced at that meeting, defines a new kind of regionalism. It’s an arena where actors contest for control. And it has concentric circles of stakeholders and powerbrokers. It’s ripe for a multilateral mechanism—but none yet exists.

The report concludes with listing the preconditions for peace in the Sudans today, concluding that they are not currently in place. That’s discouraging for those trying to use the old tools for mediation. It’s a challenge to redefine the problem—to think in the right box—and identify the right tools.