Introducing the updated WPF dataset of historical famines

If we want to prevent or relieve famines we need data. We need to know where and when they strike and why.

If we want to save lives we need to understand who is in danger of dying from hunger, disease, exposure and related causes.

For forty years there has been a global effort to collect the data to make humanitarian responses more efficient and effective. At the forefront of these efforts was the United States Famine Early Warning System Network, FEWS NET.

In January, as a result of the executive order signed by President Donald Trump shutting down USAID, FEWS NET was suspended, purportedly in the name of efficiency. That was followed by an instruction that there would be a waiver for life-saving humanitarian assistance. FEWS NET remains offline.

That’s like telling emergency room physicians to continue working but stopping them using any kinds of specialist testing.

Accurate, timely, objective information is an essential pillar of any efforts to prevent or relieve famine.

For that reason the World Peace Foundation has developed a dataset of historic and contemporary famines.

The historic famines dataset is an expansion on the catalogue of historic famines published in 2016, including new famines, both recent and historical, and new data on old famines.

The main dataset of historic famines is available here. A list of bibliographic sources is here.

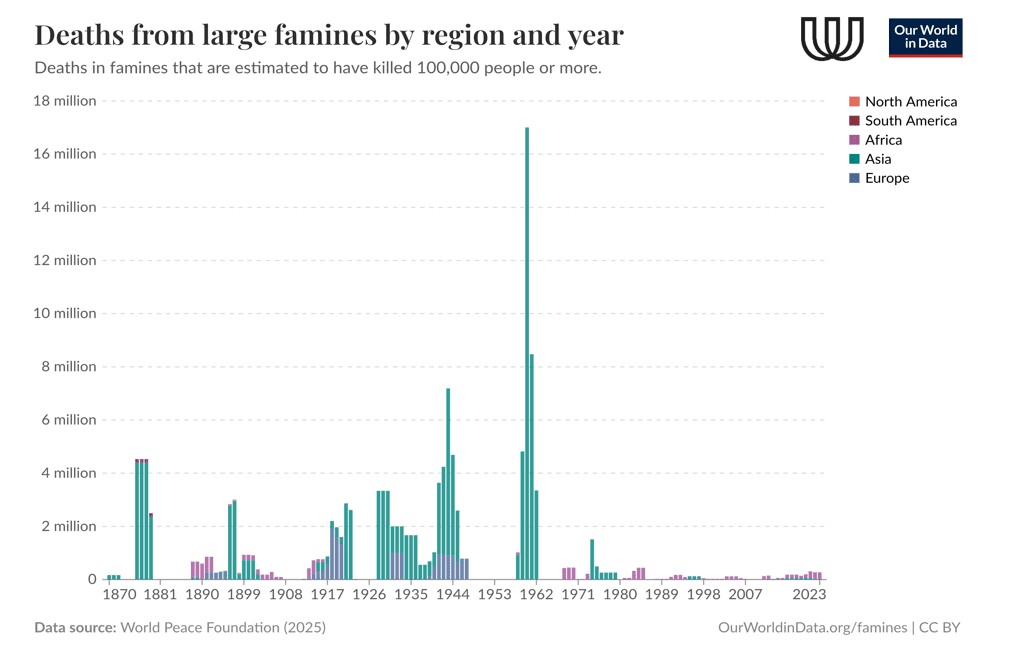

For assessing historic famines, we used a threshold of 100,000 excess starvation-related deaths over a specific time period—‘great famines’.

The contemporary famines dataset draws on the UN-accredited Integrated food security Phase Classification (IPC) system, which is the authoritative diagnosis of impending or ongoing famine. The IPC uses a rigorous method for identifying when and where famine is occurring, according to its metrics of intensity of food insecurity, malnutrition and mortality in a given location. It is a consortium, and FEWS NET was until this year its single most important partner.

A catalogue of recent famines and near-famines, using the IPC formula, is here. This derives from data in the IPC population tracking tool.

The two listings use different approaches to measuring famine. In later posts we will explore the similarities and differences.

The historic dataset is imperfect. Measuring famine mortality is difficult and controversial. There are many methodological challenges that are outlined in an annex, available here. Our dataset is best seen as listing or a catalogue rather than the kind of dataset that can be subjected to complex multivariate analyses.

However, we can still make some powerful generalizations.

The updated famine listing confirms some findings from its predecessor, refines some analyses, and introduces some new findings. Let’s highlight some.

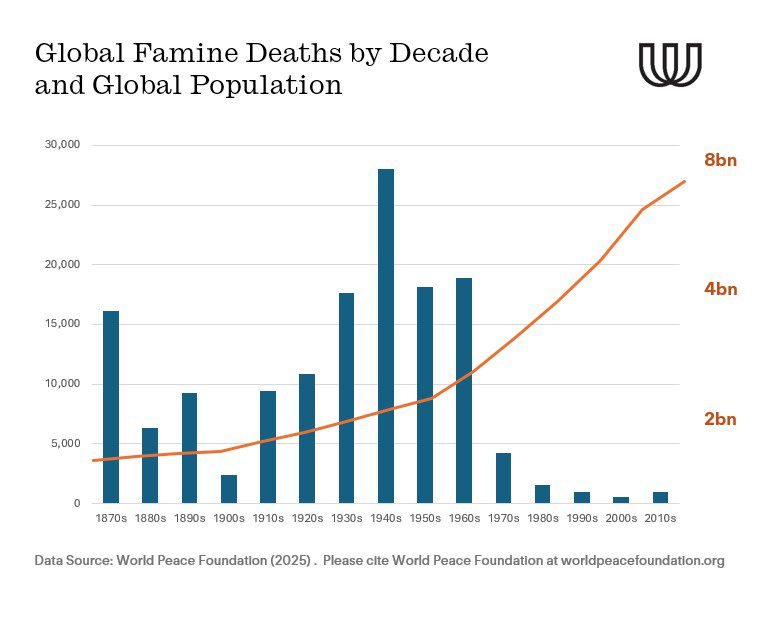

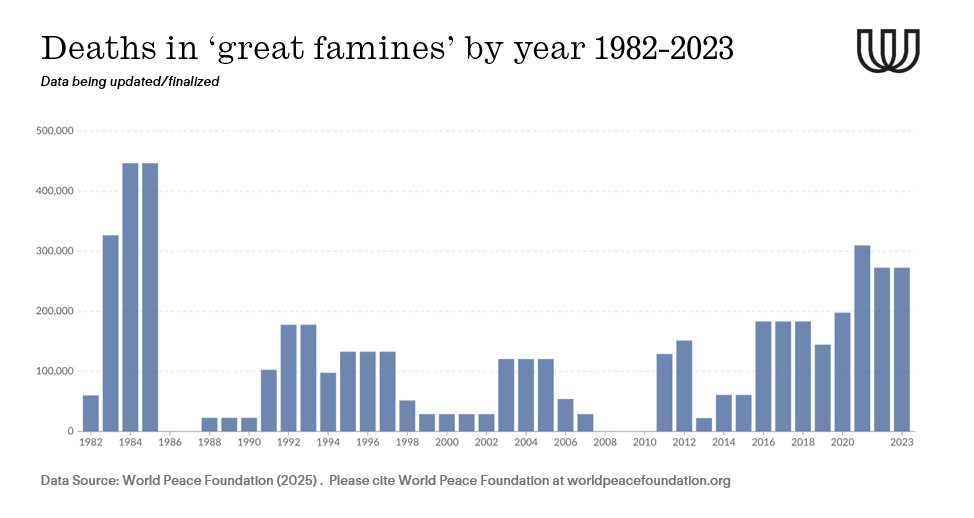

First, today’s famines are far less lethal than those of the period up to the 1980s. During the first decade of this century, famines all-but-disappeared. I was hopeful that they would be consigned to history.

Second: in the last decade years we have seen a reversal of the hopeful long-term trends towards the end of famine. The numbers of people dying in great famines has started to increase.

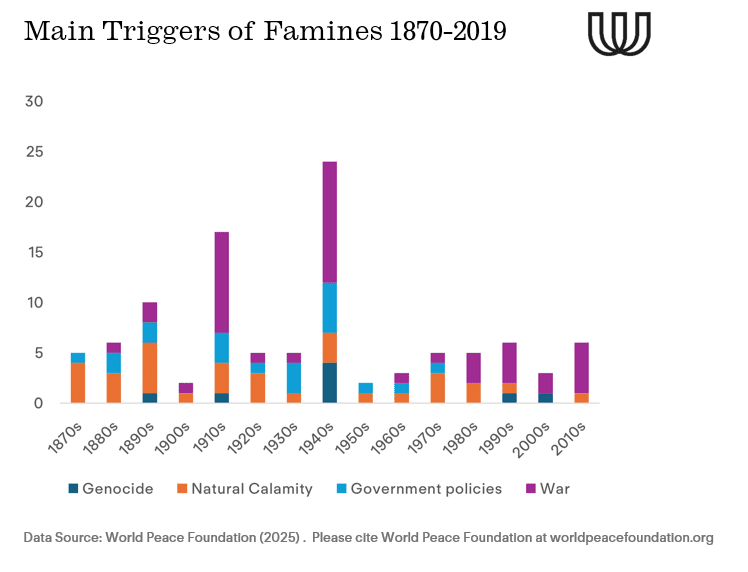

Third: while all recent famines are ‘man-made’ and not attributable to climate or natural disaster, this is nothing new. The great majority of famines since 1870 are man-made in one way or another.

This graph shows the triggers of famine events by decade, classed into four categories: natural calamities, government policies, war and genocide.

It follows that journalists and policymakers shouldn’t use ‘man-made famine’ with a tone of surprise. It’s nothing new. For example, António Guterres, Secretary General of the United Nations told the UN Security Council in 2021, ‘Famine and hunger are no longer about lack of food. They are now largely man-made—and I use the term deliberately.’

He could have said the same thing fifty or a hundred years ago.

Researchers have been carefully documenting the impacts of conflict, errant and malicious government policies, and the shortcomings of humanitarian aid for many decades.

Drawing on the causes of famines described in the academic sources we used, here is a word map:

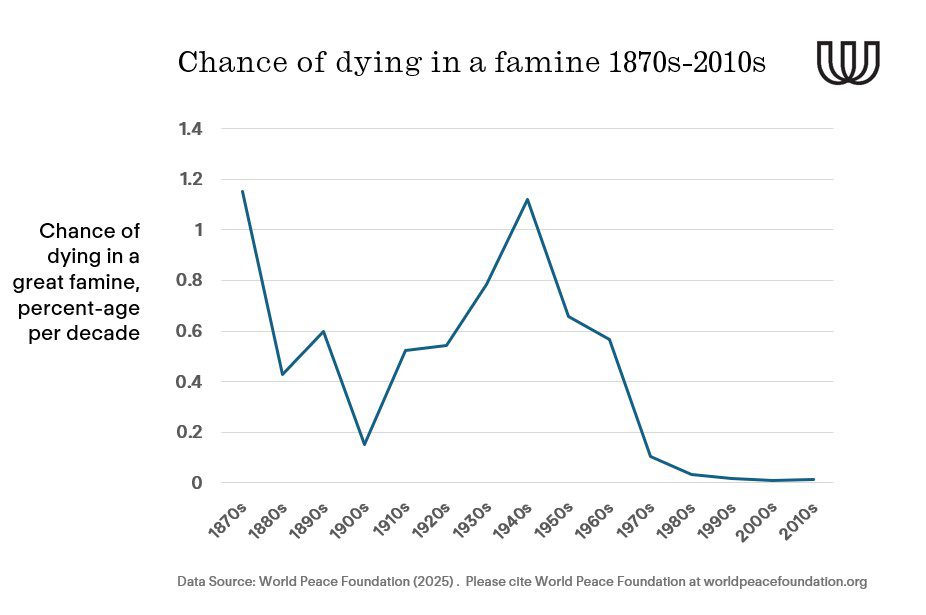

Upcoming blogs will delve deeper into some of the key findings of the project. But here is one: there’s no simple link between population growth and famine. At a global level, while the population has risen, the risk of dying in famine has declined.

For only two decades has the risk of dying in a great famine been more than 1 percent per decade, or 0.1 percent per year.