The social meaning of famine is to be found in memory.

A just-published special issue of Third World Quarterly on famine and memory, includes contributions on Bengal (India), Biafra (Nigeria), Brazil, Cabo Verde, China, Iran, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Timor Leste. These are historians’ writings, bringing famines into memory studies, reflecting on how subaltern memories persist despite official denial or disinterest, and exploring what those mean for contemporary societies.

Scholarship of this kind is in itself an act of remembrance and thus the beginning of justice. It is extending recognition and dignity to the victims and survivors, acknowledging the wrong of famine for what it is.

In my concluding reflection on the case studies, I turn this on its head, asking what memory brings to the theory of famine.

During my fieldwork in Darfur during and after the famine of 1984-85, even in the depths of hunger and distress, the people with whom I spoke wanted to tell me about how the then-current famine compared with what they understood about earlier famines. Nothing comparable had happened for forty years. This means that the local understanding of famine is constituted from social memory. This is hugely significant: in Darfur, grandmothers’ remembered practical knowledge about wild foods—where they could be found, how they could be prepared—was essential to survival.

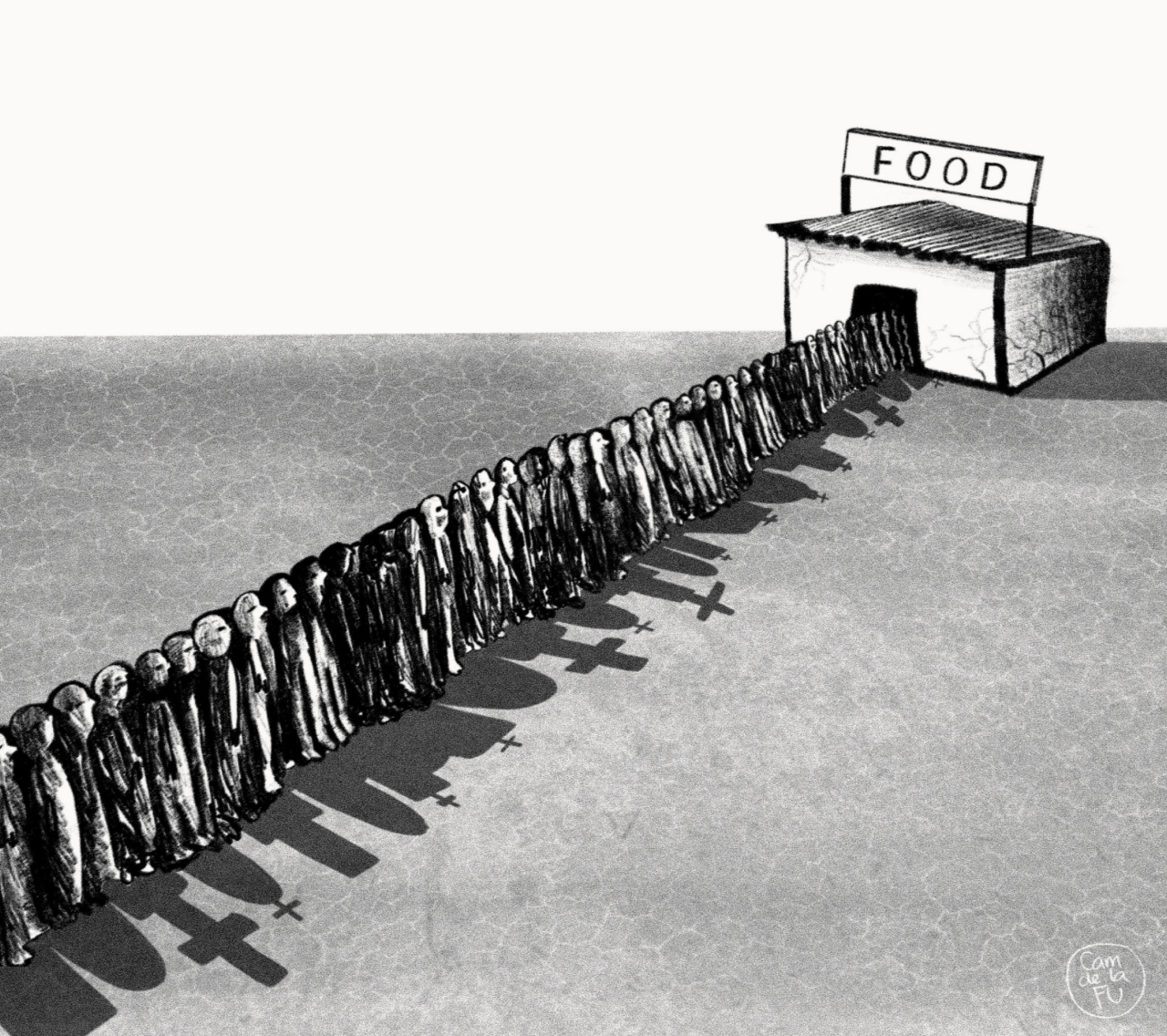

This is not an isolated insight. Everywhere we turn, the lore around past famines, the social meanings ascribed to hunger, deprivation and the strategies needed for survival, are the raw material for understanding what they mean today, and how people will respond when extreme hunger strikes.

Famine theory has languished for years. Metrics for malnutrition and food insecurity have displaced social nutritionists’ approaches, while vernacular understandings of famine are a fringe topic pursued by anthropologically-sensitive aid workers. This is a vast and needless gap in the academy and among practitioners, which leaves the people who suffer famine disempowered and aid workers handicapped.

Memory studies can revitalize the social science of famine and in turn breathe new life into the stale policy prescriptions that drive famine response.