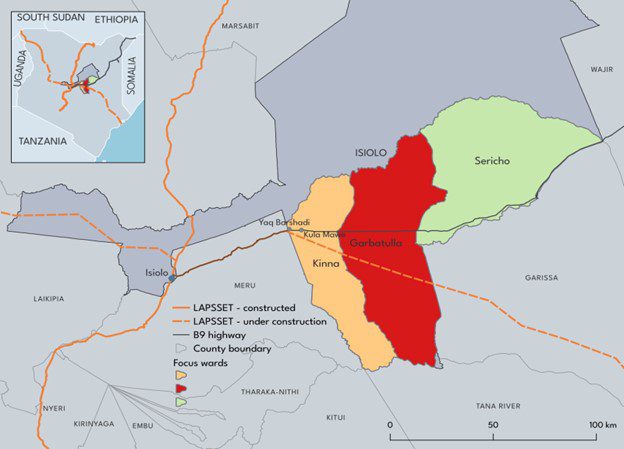

The new report, “What’s in a line?” explores the competing and clashing concepts of land and territoriality between the Borana pastoralists of Isiolo and Kenyan authorities engaged in regional infrastructure development. Grounded in qualitative methods and drawn on the legibility theory manifested in Seeing Like a State, the great work of James Scott, the paper looks at the territorial change in the Waso Borana rangelands of the Kina, Garba Tula, and Sericho wards.

Pastoralists view the land, ecology, and their livelihood as inseparable elements, with their way of life directly dependent on their access to mobility and the diverse breeds of livestock they have raised for centuries. In northern Kenya, home to millions of pastoralists, most pastoralist rangelands constitute fragile ecosystems that require careful and adaptive use. With generations of experience navigating these harsh and variable environments, pastoralists possess the unique capacity to use these environments sustainably by following seasonal patterns and matching livestock needs to microclimatic conditions across the rangelands.

To ensure the extensive and sustainable use of these ecosystems, pastoralists practice seasonal mobility, allowing livestock to graze in a way that causes minimum ecological degradation. Their seasonal movement enhances both the animals’ productivity and reproductive success. Their ability to read and respond to environmental variations reflects a sophisticated form of indigenous ecological knowledge—one that is particular to pastoralist communities and shaped by their generational experience, the finna.[1]

Since its inception, the Kenyan state has systematically marginalized pastoralist regions in national development planning, excluding them from meaningful participation in the country’s broader development agenda. For decades, state efforts have focused on appropriating vast tracts of land for conservation purposes, prioritizing wildlife as a key contributor to GDP through the tourism sector, which generates foreign exchange earnings.

For the Waso Borana of Isiolo county, this marginalization is particularly acute, as historical patterns of injustice continue to manifest in various forms. Northern Kenya, often framed as a development frontier, has been witnessing the implementation of major projects such as airport construction, wind farms, and large-scale infrastructure developments—among them, the Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor, which is threatening the mobility of Waso Borana pastoralists. This research focuses on a specific section of the LAPSSET project at the intersection of the Modogashe–Isiolo road, particularly in Kina, Isiolo County, where the proposed corridor is set to demolish the village of Yaq-Barsadi. Adjacent to this village, situated beneath a plateau, lies a pair of sacred grove trees (Yaq), that face imminent removal to make way for the 500-meter-wide LAPSSET corridor, which will include a highway, railway, and oil pipeline.

The marginalization of the Waso Borana clearly comes into focus where their sacred and symbolic groves are targeted for destruction. Although the Modogashe–Isiolo road has narrowly avoided encroaching on a culturally significant grove—thanks to sustained advocacy by local elders and youth—concerns remain acute. Starting in 2017–18, community members escalated the matter to the National Museums of Kenya, requesting the formal registration of Yaq (grove trees) as protected tangible heritage. While the grove trees near the village were still standing at the time of data collection, the LAPSSET project threatens to demolish the entire village of Yaq-Barsadi, placing the grove’s future in jeopardy. Authorities have instructed villagers not to renovate or construct new houses, as demolition is imminent. Despite continued anticipation, residents have awaited compensation for appropriation of their lands since 2017.

Both the LAPSSET and Modogashe–Isiolo roads have been identified as critical infrastructure developments with far-reaching implications for pastoralist communities in the wards of Kina, Garba Tulla, and Sericho. Despite promises of minimal last-minute consultation, authorities have yet to provide any form of compensation for the Waso Borana pastoralists. In the case of LAPSSET, the government may not provide any compensation for the estimated 55 km² of Waso Borana pastoralist land that will be permanently lost to the project. These roads are poised to impose new territorial boundaries that obstruct pastoralists’ seasonal and daily mobility, thereby threatening pastoralist livelihoods and endangering the well-being of both livestock and humans. The absence of underpasses along the construction of both roads—for people and animals, including in areas with key boreholes—further exacerbates these impacts by hindering access to essential water sources and pasture lands.

The Waso Borana pastoralist of Isiolo county need the incorporation of underpasses or overpasses in infrastructure projects in the Waso rangelands to safeguard their access to critical resources essential for sustaining their livelihoods. Robust and socially just infrastructure planning demands the inclusion of the substantive participation of these communities, strict implementation of the Community Land Act, and the comprehensive enactment of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent standards. Moreover, equitable and adequately structured compensation mechanisms must be instituted to redress the substantial land dispossession that the Waso Boranas are poised to experience because of ongoing and future infrastructure development interventions.

[1] An interwoven concept and notion of fertility/reproduction (finna) and the cosmic order. Finna also constitutes the ethical principles and common code of practice, based on a deep respect for ecology (cheera fokkoo), where Borana traditionally coordinate their relationship with the environment around them in relation to their daily life and livelihoods (Arero, 2007).