Essay originally drafted for the WPF seminar, ‘What Animates and Challenges the Possibilities for Collective Action today?‘ held in September 2023.

Questions posed by the conference:

- Context: how has collective action been conceptualized?

- Where is collective action being innovated and to what ends?

- Inversely, what are the obstacles and limits of collective action?

- What do these examples tell us about how collective action is being re-conceptualized today?

In addressing these questions I will focus on rural spaces in the global south, where livelihoods are precarious in old and new ways. I divide my topic in two parts: access to land (as a source of livelihood), and access to paid work (sufficient for a decent life). I briefly describe what makes land or labour-based livelihoods precarious, then consider the kinds of collective action that emerge in response, together with their limits. I illustrate with material from my field-based research in Indonesia, and look forward to the opportunity for us to discuss whether the problems, processes and practices I identify are more broadly observed.

Apologies for the self-citation: this essay presents in very brief and truncated form some ideas I have developed in previous work. I do not attempt to summarize the contributions of the many scholars who have worked on these topics, as I would in a formal paper. These are notes intended to indicate some ideas and research findings I can contribute to our collaborative reflections.

Precarity in Access to Land as a Basis for Livelihoods

Land (and land-based resources such as rivers, forests) are key to rural livelihoods. Access to these resources enable rural people to put themselves to work to support their families, hence access is key to their livelihoods. As what can go wrong?

Sources of precarity in land access

In Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia (Hall, Hirsch, and Li 2011), my co-authors and I examined the different powers that may be deployed to render rural peoples’ access to land precarious. We identified four powers:

- The power of narratives that de/legitimize particular land uses (eg forests should be conserved, hence forest-based livelihoods are illegitimate).

- The power of regulation (zoning laws, property laws, customary laws) that formally recognizes some land uses/land users as legitimate, and informalizes or disallows others

- The power of the market that organizes access to land as a commodity that can be bought, sold or rented. You can only access this land if you can afford to buy it or rent it. iI not, you are excluded.

- The power of material force which can take the form of interpersonal violence (guns, sticks) or “infrastructural” violence (the gate, the fence, the re-routed river, the bulldozing of mixed farms and their replacement by mines or plantations).

Collective responses and their limits

Each of these powers constructs and delimits a field of possible actions and reactions, some of them collective.

In relation to narratives, we may ask: can the narrative be changed? An example of this is the attempt to shift the narrative legitimating exclusion of customary landholders by presenting them as forest-destroyers to a narrative that presents them as forest-guardian. Promoting this shift has been a collective and multi-scalar effort, involving scholars, activists, and forest-dwelling people. Its results have been mixed: the narrative of forest-destroyer still exists; and the expectation that forest-dwelling people will be conservation-oriented has led to new exclusions that narrow and limits livelihoods. For example in Indonesia customary landholders/indigenous people have been involved in collecting and producing commodities for global markets for at least three centuries, but the counter-narrative designed to protect them now consigns them to a non-market niche (Li 2014a).

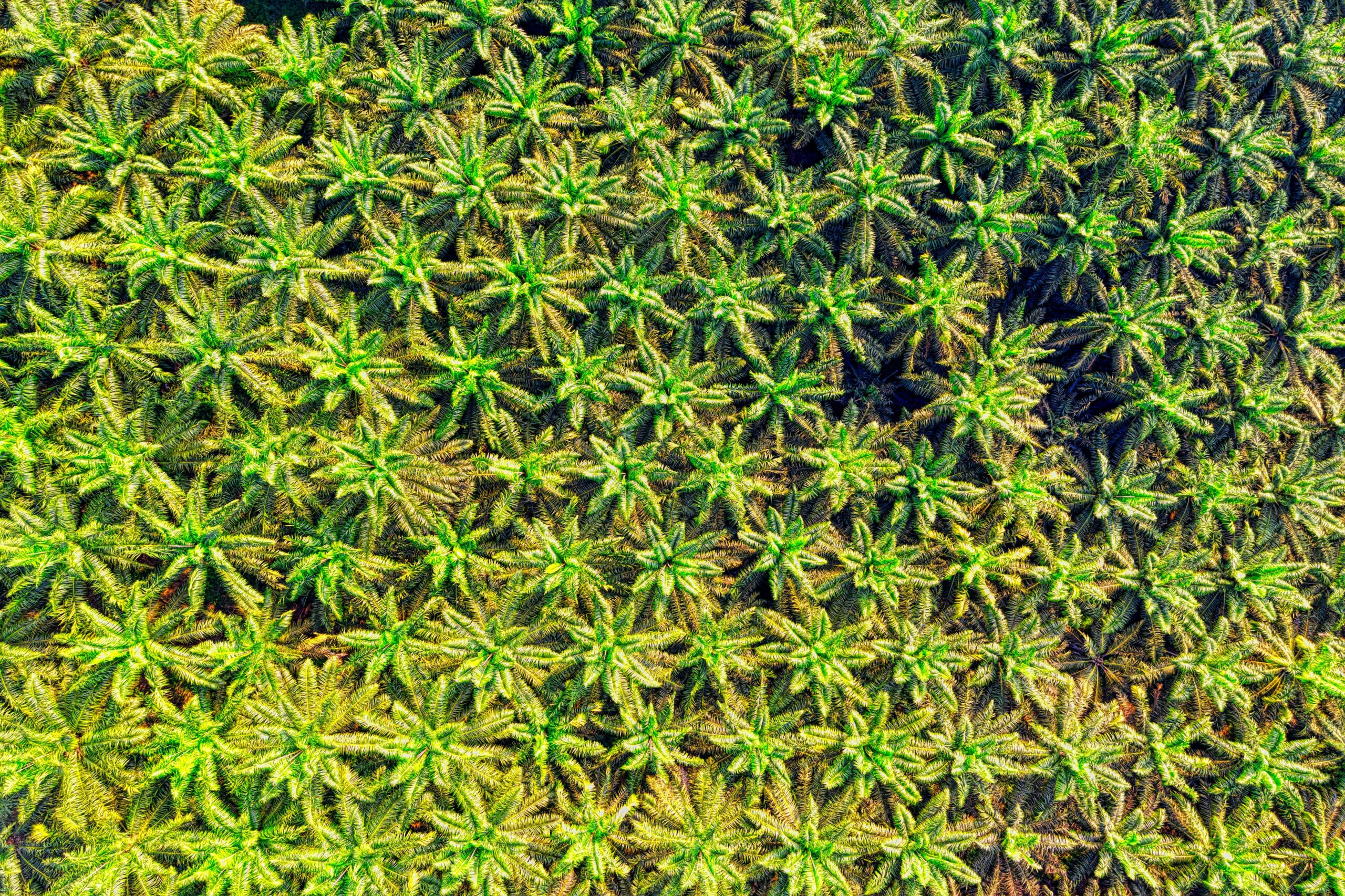

In relation to regulation, we find again a multi-scalar mobilization that attempts to reorient laws and regulations to be more favourable to customary land users and small scale farmers. In much of Southeast Asia (also Latin America) this has resulted in laws that recognize customary collective tenure in different forms. The outcome, again, is mixed. The bounding of customary territories creates insiders and outsiders; and it often delimits tiny areas of land, far smaller than the land granted to corporations for plantations, mining etc. In Indonesia, mobilization for customary land rights produced a weak form of legal recognition in 2012 and the legal delimitation of a few thousand hectares of land; in the same period, ten million more hectares were granted to corporations as plantation concessions for oil palm (Li 2020).

In relation to markets, collective action is more difficult to imagine or implement. Although some established advocacy agendas consign customary land-holders to a non-market niche, in many Southeast Asian contexts indigenous farmers are accustomed to producing for markets, and they may have informal land markets that are new or well established. Hence the idea that goods, land and labour have prices is not – as Polanyi suggested – a “great transformation” or the end of society; it is sometimes surprisingly familiar, even banal. The idea that some people will prosper and others will fail and fall into debt is also no surprise to rural Southeast Asians. I examined this kind of banality in Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier (Li 2014b). So what is there to be resisted? Concretely, people mobilize not against the power of markets, but against the manipulation of markets through monopoly or monopsony practices that exclude or cheat them. The classic example of the bread-riot as an expression of moral economy was not a protest against the concept that bread should have a price – it was a demand for a just price that was not inflated by speculation and hoarding (Thompson 1971). Often, what people want is not less market but a fair and open market in which they can compete on a level playing field. Ironically, it is the so-called capitalist enterprises (eg plantation corporations) that operate on non-market principles, gaining land concessions for free or at low prices, and enjoying many other government subsidies.

Material force is the image most readily associated with collective action, as villagers attempting to hold onto their land confront bulldozers or armed guards and risk death, injury, incarceration or eviction. The price for collective action can be very high. It also needs to be examined in a temporal frame. The moment of resistance to eviction, for example, is dramatic, deadly, and sometimes heroic. But what happens next is a long-drawn out process of small skirmishes and accommodations. In my recent book (with Pujo Semedi) Plantation Life: Corporate Occupation in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Zone (Li and Semedi 2021) we draw attention to the spatial, temporal and institutional dimensions of occupation as a form of built-in or infrastructural violence. Once an oil palm plantation is installed, it stays. Once the corporation has taken control over land, it never reverts to the customary landholders. Government officials become collaborators, formally tasked with facilitating the work of plantation corporations. What kind of collective action could remove an occupying force? Our ethnographic research showed that villagers whose land (and lives, and institutions) have been occupied by corporate

plantations struggle to identify a front of collective action. Instead, they engage in theft, blockade, arson and other forms of short-run and small scale action that may produce small victories, but leave the structure of the occupation unchanged.

Access to Work as a Source of Decent Livelihoods

It is important to note that access to jobs is one of the principal narratives legitimizing the allocation of rural land to corporations for the purpose of mining, plantations etc. The narrative is itself a weapon, as it underestimates or renders invisible the kinds of work and livelihood that rural people generate for themselves when they have access to land. The idea of the steady, well paid job complete with job-associated benefits like pensions and health care is widely understood as the natural and proper evolution from farm to factory (or plantation), from village to city, from informal to formal, from unproductive to productive and so on. These narratives are resolutely linear and profoundly misleading as a generalizable characterization of the transformations occurring in rural areas of the global south today, where the trajectories to and from paid work are highly diverse (Ferguson and Li 2018). In many contexts, rural livelihoods are being undermined (through loss of access to land, adverse prices, demographic shifts, among others) but no “proper jobs” are on offer, either in the countryside or the city (Li 2011). Here are a few exclusionary scenarios:

- Lack of Jobs: Few jobs are available because large enterprises require few workers.

- Lack of access to jobs: employers favour particular ethnic groups, age groups, genders etc.

- Jobs are of poor quality: low pay, casual, outsources, unprotected.

- Migration is risky: the march to the city “to get a job” presents huge risks, especially for people without the necessary languages, ethnic or kin networks, skills, legal status etc.

Collective responses and their limits

Classic modes of collective action in relation to work are wild cat strikes, or the formation of unions, work committees etc; and the development of legal regimes that protect worker rights. These forms of action work best in relation to people who have jobs – and not so well for people who lack access. What kinds of leverage are available to people who are excluded from the arena of paid work, those who form a “relative surplus population” irrelevant to capital at any scale?

One form of action is preventative: rural people often fight very hard to retain access to farm and forest land precisely because they know that the livelihoods they can secure for themselves are far more solid than any they will realistically be able to access as wage workers. There is a parallel in urban contexts: squatters and shack dwellers mobilize collectively against eviction because access to a living space in the center of the city is the key to their (usually informal) livelihoods: their daily incomes are not high enough to pay bus fares. Struggles against hikes in bus fares and the price of fuel are also struggles over access to work, and over the margin between costs and revenues in the activities that constitutes their livelihoods.

Where laws protect workers, the struggle is often over implementation. Less than 10% of Indonesia’s work force is covered by the labour law, which excludes casual and outsourced workers. For the 10% who are formally protected, enforcement is scarce: less than 5% of Indonesia’s large enterprises are inspected annually. Formally employed workers have the right to form unions, but in practice union organizers face intimidation and dismissal (Li 2017b).

A crucial form of response to precarious livelihoods takes the form of what James Ferguson calls “distributive labour”: the work of putting oneself in a position to receive livelihood resources (shelter, food, money) from another person, be it family member, patron or neighbour. As he observes, there is nothing automatic about distribution – no “moral economy” that ensures survival for all. Some people are in fact abandoned. And forging and maintaining distributive relations takes work: such relations can attenuate or collapse. There is a collective element to this kind of distributive economy, but there is no fixed unit that takes responsibility for its “members” (the family, the neighbourhood, the village, the ward). In both country and city alike, geographic mobility, demographic shifts, class differentiation and many other elements are implicated in the forging or loss of distributive relations (Ferguson 2015).

What of the state? “Pan, techo y trabajo” is the Spanish chant for mass street protests, and the demands are presented as demands on the state. This kind of demand makes sense in some contexts, but would be quite absurd in others, where the state has never taken responsibility for, or been held accountable for, the livelihood and well being of the population. Accounting for different forms of citizenship and different forms of the state is a comparative project worth some attention (Li 2009). “Peasants” in Thailand successfully make demands on the state for rural infrastructure, secure land tenure, farm supports etc; in Indonesia such demands would fall on deaf ears, so no one seriously attempts to mobilize collectively around them (Li 2017a).

Works Referenced

Ferguson, James. 2015. Give a Man a Fish. Durham, N.C. : Duke University Press.

Ferguson, James, and Tania Murray Li. 2018. Beyond the” Proper Job:” Political-economic Analysis after the Century of Labouring Man. Cape Town: University of Western Cape PLAAS Working Paper 51.

Hall, Derek, Philip Hirsch, and Tania Murray Li. 2011. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press.

Li, Tania Murray. 2009. “To Make Live or Let Die? Rural Dispossession and the Protection of Surplus Populations ” Antipode 41 (s1):63-93.

———. 2011. “Centering Labour in the Land Grab Debate.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (2):281-98.

———. 2014a. “Fixing Non-market Subjects: Governing Land and Population in the Global South.” Foucault Studies 18:34-48.

———. 2014b. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

———. 2017a. “After Development: Surplus Population and the Politics of Entitlement.” Development and Change 48 (6):1247-61. doi: doi:10.1111/dech.12344.

———. 2017b. “The price of un/freedom: Indonesia’s colonial and contemporary plantation labour regimes.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 59 (2):245-76.

———. 2020. “Epilogue: Customary Land Rights and Politics, 25 Years On.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 21 (1):77-84.

Li, Tania Murray, and Pujo Semedi. 2021. Plantation Life: Corporate Occupation in Indoensia’s Oil Palm Zone. Durham N.C. : Duke University Press.

Thompson, E.P. 1971. “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century.” Past and Present 50:76-136.