By Nisar Majid and Khalif Abdirahman

A Two-Year Presidential Extension in Somalia?

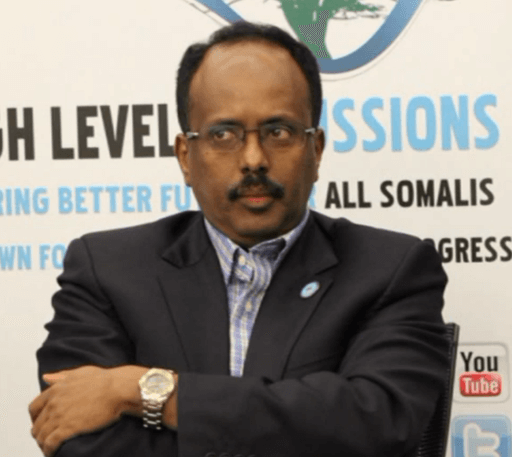

Somalia’s President and Lower House of Parliament have just extended their terms in office by two years, after many months of wrangling. Many – but far from all – of Somalia’s international partners have been vocal in their criticism of this turn of events with various sanctions being threatened, including of the very recognition granted to the government only nine years ago.

Why such attention? At first glance Somalia appears rather peripheral to global affairs. However, the country repeatedly rises in profile with piracy, terrorism and famine amongst the headlines generated. In recent years, the commercial opportunities through the many seaports that connect Somalia (and Somaliland) to markets in Ethiopia and Kenya have added to this interest, as have developments in the oil/gas sector. The current political crisis is the latest such episode but reflects alarming wider regional tensions and conflict.

It is worth reflecting for a moment on the nature of Somalia’s government and political predicament (discussed in some detail in Mary Harper’s African Arguments book). The federal system consists of a central government along with five member states (Somaliland is officially the sixth state but seeks independence and acts in its own right as an equivalent state). Each of these member states has a certain – and varied – degree of autonomy, in political, economic and social terms, from the central Government in Mogadishu.

This governmental system holds limited territory, with much of southern Somalia (especially South West State, Hirshabelle and Jubbaland states) under the influence of Al Shabaab, where only urban centres and some rural areas are controlled by combinations of government forces and AMISOM. Adding to this complication, the leadership in many of the federal member states represent the most powerful militarily clan-based groupings, and not necessarily the majority of people within those states. These excluded groups look to the federal government or indeed Al Shabaab for some degree of representation or recourse.

The incentive for this federal system to stay together is that it brings with it large amounts of foreign resources and the power and status that sovereignty generates. That the Government of Somalia exists at all, as a recognised international state, is an achievement of sorts and provides a symbol of hope for many Somalis (and for many in the wider international community); a sign that, after its collapse thirty years ago, a more optimistic future is possible or indeed on the way. However, for many, this is little more than a facade, and brings little tangible benefit.

The degree to which legality or the constitution informs political processes, including the decision to grant a two-year extension, is a moot point. The constitution is fluid and ambiguous and there is no official body, such as a constitutional court, to execute legislation. This is a situation that has been wilfully maintained by elites that wish to avoid such accountability. Political processes work on the basis of deals and arrangements that are subject to change over time. They also work on the basis of money and/or coercion; this is most evident during election periods.

Somalia’s political trajectory is strongly influenced by its relationship with a wide range of international actors; this has intensified over the last ten years. Understanding some of these relationships helps clarify current political dynamics.

The powerhouse in the Horn of Africa is Ethiopia and under the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia has lent its political and military support to Somalia’s President. This has been done in collusion with Eritrean President, Isaias Afewerki; an Ethiopia-Eritrea-Somalia axis has emerged within the last two-to-three years in the Horn.

Since 2018, elections have been held in the five Federal Member States of Somalia. In all of these elections the ruling cabal in Mogadishu has intervened, using money and coercion in attempts to install compliant leaders. Ethiopian support was clear in this. These interventions succeeded in three states, South West State, Galmudug and Hirshabelle, which have remained supportive of President Farmajo.

They failed however in two states, Puntland and Jubaland. The leaders of these two states, along with opposition figures in Mogadishu, have led the resistance to Farmajo’s autocratic tendencies. However, none of these opposition leaders represent a more progressive politics and are arguably even less popular than the President himself in many circles. President Madobe of Jubbaland, a vocal critic of the government, has arguably only remained in power due to the support of Kenya and the strength of his own militia. Kenya, along with Djibouti and Somaliland, oppose this Ethiopia-Somalia-Eritrea axis. Kenya has its own interests in Somalia vis-à-vis a maritime dispute which includes areas of oil/gas potential in border areas with Somalia. For some, Farmajo has represented a strong hand vis-à-vis Kenya and internationally. President Deni of Puntland is himself an autocratic figure, increasingly unpopular in Puntland, and with aspirations to the national Presidency.

These intra-regional tensions have been compounded by competition within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) that has been playing out in the Horn of Africa; with Turkey and Qatar supporting the Federal Government in Mogadishu, and the UAE supporting various opposition groups. Somali elites are experts at playing off these different foreign interests in order to further their own individual or group agendas, a practice developed by President Siad Barre in the 1970s and 1980s.

Western donor countries have played their part, perhaps less actively supporting particular sides, but nevertheless giving mixed signals about political direction in recent years and playing down indications of Farmajo’s autocratic tendencies.

That said, it is not clear how directly foreign interests have been involved in the process to decide on the two-year extension. Insiders in the Somalia parliament claim there has been no widespread pay-off (of parliamentarians), although they do not discount that a very selective use of money may have taken place.[1] The influence of Isaias Afewerki of Eritrea and Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed – in some form – cannot be discounted given pre-existing relations and the political systems in both countries. The obstructionism of Presidents Deni of Puntland and Madobe of Jubbaland, and the personal grievances they have with Farmajo, are further aspects of these dynamics. Ultimately both Deni and Madobe (and other opposition figures) have not been confident that they could defeat Farmajo in any form of election.

Given these factors, Somalia’s predicament is extremely depressing. An optimistic scenario is that this facade of government – the federal system – will continue much as it has for the last few years, benefiting a small elite with people continuing about their lives as usual. The business community and traditional local livelihoods, based on livestock and agriculture, are more important to the lives of everyday people than what happens at government level.

A pessimistic scenario is more worrying but far from clear; for all the limitations of government, the federal system – and the political compact it signifies – has at least stopped large-scale violence and represents an accommodation of belligerents who might otherwise resort to fighting. However, the threat of serious conflict deserves closer scrutiny. This threat is frequently evoked by political entrepreneurs for their own personal agendas, to scare the international community into backing down over conditionalities or favouring their interests. This narrative has been used for months by some opposition figures, with only localised incidents having taken place, such as the 25th January attack on Belet-Hawo. Ultimately, and depressingly, far more people die from food insecurity, disease and malnutrition in Somalia than as a direct result of conflict or violence.[2]

Al Shabaab can be seen as both an inhibitor of large-scale violence (through its widespread presence, limiting clan-based mobilisation) as well as a security threat in its own right. The warlord era, and the mobilisation of clan militias as occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s, is over. There is limited appetite for such fighting although it would be foolish to completely discount such a possibility, amidst the incitement currently taking place.

The threat of Al Shabaab in a deteriorating political context is unclear. While the group remains a security threat within Somalia and in neighbouring countries, most notably Kenya, observers suggest it is less ideologically driven today and is more driven by financial interests; a mafia-type organisation. The economic reach of the group is formidable. It is able to tax all sectors of the economy far more effectively than the government, regardless of whether it physically controls territory. It provides a justice capacity that outcompetes equivalent government systems. Simplistic assumptions of an organisation that cuts off peoples’ hands or heads are much exaggerated; many people turn to Al Shabaab – including government figures – as its justice is considered fair (certainly fairer than alternatives) and comes with an enforcement capacity. Somalia has been the recipient of more drone attacks than any other country in recent years, yet the group remains pervasive and has extended its reach.

To conclude: there is no doubt that President Farmajo has attempted to impose an autocratic character on Somalia’s federal system, most likely drawing on the example and support of his closest regional allies. In this he has failed to provide leadership for a more collusive or cooperative political system that might enable further ‘progress’ within the country (and in this the Parliament has had an excuse to extend its own term). However, whether any such figure currently exists within the political elite is highly questionable. A deeply fragmented regional and international political arena has provided the context within which established elites continue to cling on to power or attempt to return, in order to pursue their very narrow agendas.

[1] The suggestion, for which there is no evidence as yet, is that a small number of key individuals may have been paid.

[2] Admittedly the relationship between these factors and conflict is complex; see Maxwell, D., Khalif, A., Hailey, P. and Checchi, A. (2020), Determining Famine: multi-dimensional analysis for the 21st Century, Food Policy, 92, 101832 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306919220300166?via%3Dihub), for a discussion of famine dynamics in several countries including Somalia.

Dr. Nisar Majid was Research Director at the Conflict Research Programme (Somalia portfolio) at the London School of Economics (2018-2021), where he remains attached.

Khalif Abdirahman was a core member of the London School of Economics Conflict Research Programme (Somalia portfolio) (2018-2021) and is a Fellow at the Rift Valley Institute.

Photo: Somali diplomat, professor, and politician Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo”, former Prime Minister of Somalia and founder and Secretary-General of the Tayo Political Party, Deeqosonna Warsame (CC BY 3.0)