In a just-published paper in the journal Disasters, entitled ‘Hunger in global war economies: understanding the decline and return of famines,’ I argue that the decline and return of famines over the last fifty years can best be understood through the ‘war economy lens.’ This lens brings three elements into focus: how a state or insurgent pays for its war; how it inflicts economic damage on its enemy; and how it justifies these actions.

This lens involves re-appraising the hegemony of the ‘Pax Americana’ from the 1980s until about 2015 as a unique kind of war economy; examining the challenge subsequently posed by the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) club over the last decade; and delving into the subaltern criminalized war economies that have become entrenched in the zones of contestation, which are also the places where faminogenesis is most acute.

The paper is part of a special issue of Disasters on contemporary famines and famine theory edited by Susanne Jaspars and Luka Biong Deng. ‘Hunger in global war economies’ is a reworked version of a lecture I gave at SOAS in February 2023. Because of the timeline for academic publishing, it doesn’t take account of the war economies of Israel and its regional enemies over the last 12 months. And for obvious reasons it cannot take account of the imminent Trump II administration, but I think its framing is relevant to the global economic warfare in prospect.

In this blog post I summarize some of the key points of the paper and pose questions about what it implies for the era we are entering.

The Pax Americana era was the unipolar world order dominated by the US dollar (both Wall Street stocks and Treasury instruments), the Pentagon’s trans-continental, trans-oceanic reach, and the global corporate food regime, along with liberal multilateralism. This was a period of rising living standards, cheap food, and also the widespread adoption of more open, democratic political systems. Together, these factors contributed to a decline in famines and even held out the promise of the definitive end of famine within a decade or so. This historic achievement was within grasp, notwithstanding the alarm bells sounded by climate change and the emergence of a global precariat.

Over those three decades, faminogenesis was concentrated in the frontier zones of the Pax Americana, especially where rentier political markets and the political business model of the post-2001 ‘Global War on Terror’ forged violent kleptocracies.

The Pax Americana was a war economy without precedent. The US ran its ‘forever wars’ on credit, using the exorbitant privileges of the dollar to pay for an apparently limitless hegemony. Wall Street set the pace of returns on investment, attracting capital from around the world whether the dollar was high or low, meaning that every country in the globalized economy was financing America’s deficit including its war budget. Meanwhile the Treasury oversaw the global financial switchboard, giving it extraordinary financial intelligence and opportunity for weaponizing its new-found controls.

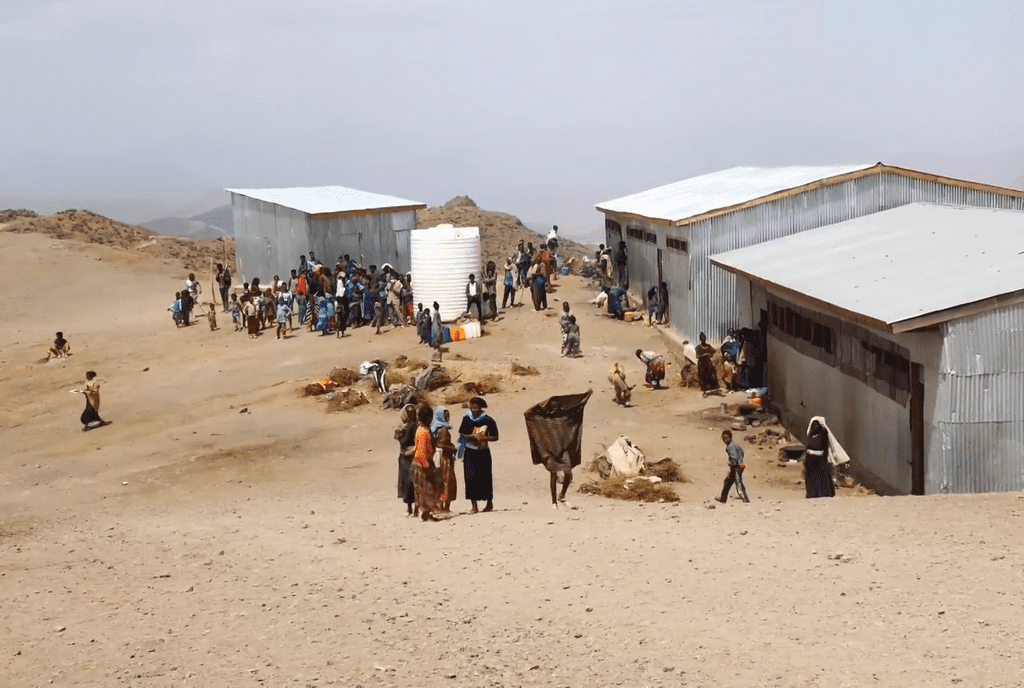

The return of famines began in the frontierlands of the Pax Americana. At first—in Somalia and South Sudan—these crises looked like hangovers from the previous era of state collapse in very poor countries. But mass starvation in Ethiopia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen signalled a new syndrome. These catastrophes were caused by a combination of emerging contests for control over key resources and strategic locations along with belligerents getting away with starvation crimes because of the collapse of international consensus on humanitarian norms.

Both the contests and the normative regression were triggered when global resentment against the overreach of the Pax Americana turned to organized resistance. The challenge was inchoate. It was initiated by the BRICS and centered on sovereignty—financial and normative. For the BRICS club members, reclaiming financial sovereignty involves proactively hedging against the domination of the US dollar. It’s not de-dollarization as such, but rather trying to establish a healthy distance from the gravitational pull of Wall Street and setting up new financial systems beyond the reach of the Treasury’s financial weapons.

The geographical frontlines of this contest runs through the greater Middle East and especially the Red Sea Arena, where BRICS added four new members this year: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, with Saudia Arabia undecided and Turkey knocking at the door. Not coincidentally, the Red Sea Arena is also the shatter zone where we see the new faminogenesis. The rising powers of the Middle East, seeking to undergird their diversifying currency options, sought to control gold, land and strategic real estate. Their political business models are transactional. Whether acting in concert or as rivals, they generate political markets in their hinterlands. When these countries turn violent, they become subaltern war economies—violent kleptocracies.

The BRICS club members don’t agree on the global normative order they want, but their collective challenge amounts to reasserting state privilege over human rights and undermining liberal multilateralism. In turn this creates a permissive environment for belligerents to commit starvation crimes with impunity.

My paper takes us this far. Where next?

The war economy lens helps us make sense of Israel’s escalation against Gaza, Lebanon, the Houthis and Iran. As Adam Tooze has explained, Israel was financially and economically well-prepared for this war, able to pay for its war effort (even without America’s open wallet), while its Arab adversaries and Iran already had very limited war finance capacities. Economically, it’s not even a serious contest. Israel can sustain its war, its enemies can only take pot shots from the rubble (albeit, in the case of the Houthis, disrupting Red Sea shipping). The logic of political survival in the shatter zone is a subaltern predatory war economy. In Gaza, we could expect to see Hamas vying with clans and Israeli-sponsored private contractors to secure the relatively modest funds it needs to remain in political business.

The most obvious development is that the international normative order has been sharply tilted in Israel’s favor.

In the Middle East, the Pax Americana was never liberal nor multilateral and the Trump Doctrine of empowering chosen allies merged into Biden’s practice of tepid rhetorical support for the multilateral order while sticking with those same favored allies. The region’s emergent peace and security architecture is the Abraham Accords, which is a war economy alliance in the three-fold sense that I use the term: it organizes war finance, punishes its enemies, and justifies what it is doing with moral claims.

This also clarifies that the Pax Americana-BRICS contest is not a new ‘cold war’ but a hot contest over the rules of the world order. Normatively, Trump’s America is joining the BRICS, intending to be the biggest bully in the playground.

Key members of the Abraham Accords alliance—notably the UAE—are also members or affiliates of the BRICS club. There is no contradiction here. The rules of the new global political marketplace are that you hedge against your friends’ bargaining strategies. It’s a post-multilateral world, in which the Trump II Administration will want to weaponize the dollar in a tactical ‘America first’ way and disregard the norms and institutions of international law. A hundred years’ worth of humanitarian principles and protections are unravelling before our eyes.