Originally published by Foreign Affairs, September 18, 2023.

In 2003, mass atrocities in Sudan’s Darfur region shocked the world. A coalition of human rights organizations mobilized in response, accusing Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and his Janjaweed militia of genocide. Although the United Nations did eventually dispatch troops to protect Sudanese civilians, the response was too slow.

Today, Sudan is again ravaged by war, and atrocities are happening on a comparable scale in Darfur. The Janjaweed’s successors are the Rapid Support Forces, and they are killing, raping and looting the same Darfuri communities. The international response to the war has been glacial and the reaction to the situation in Darfur ever slower. This is despite the fact that what is happening in Sudan is a direct outcome of the first Darfur crisis, which brought forth the RSF and its leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, known as Hemedti.

Hemedti was a junior Janjaweed commander 20 years ago, when Bashir’s government effectively declared Darfur an ethics-free zone, where impunity was the only rule. After the massacres came anarchy and then rule by Darfur’s new Janjaweed overlords, later formalized as the RSF, a paramilitary arm of the government. Hemedti’s RSF has a fighting capacity equal to that of the official Sudanese Armed Forces, which are headed by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. The two generals acted together to overthrow Bashir in April 2019, and then lived in uneasy partnership with a civilian government. In October 2021, they again joined forces in a military coup. Relations broke down and, since April, the RSF has been battling the Sudanese army for power in the streets of Khartoum.

Peace initiatives proposed by Sudan’s neighbors and the United States have focused on ending the fighting in the capital. They have overlooked the situation in Darfur, where the RSF and its local allies have relaunched their unfinished campaign of ethnic cleansing. The United Nations and the African Union—up to now apparently oblivious to the massacre, ethnic cleansing and looming mass starvation—should threaten the RSF with punitive action and dispatch military advisers to support a civilian protection force drawn from Darfurian communities.

A Troubled Land

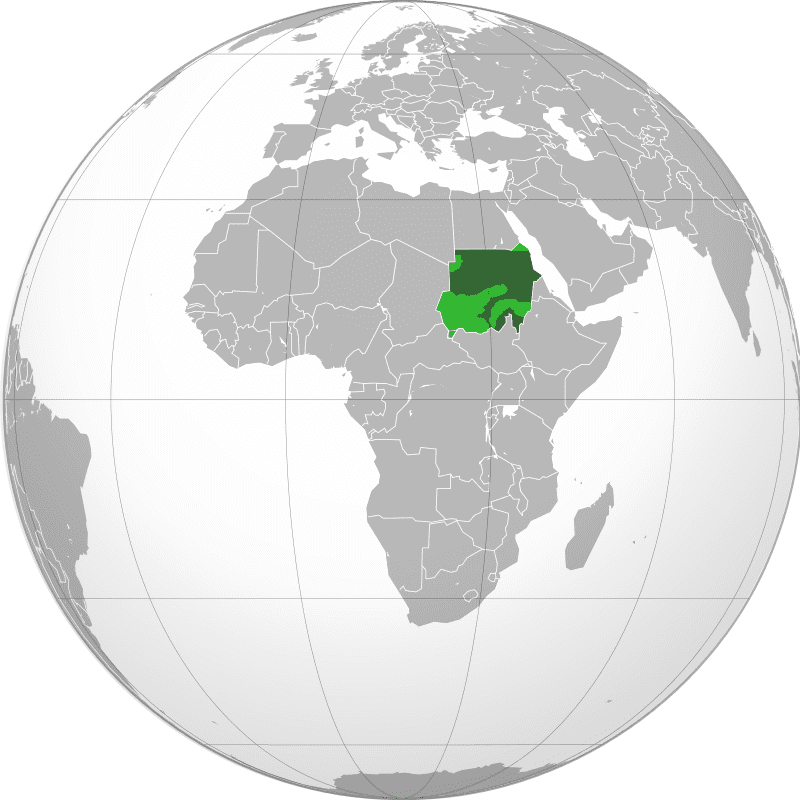

The violence that began in Darfur in 2003 had three causes. The first was Darfur’s geography. It is a vast and impoverished region, named for the historic sultanate of the Fur people, who make up a quarter of the population. A dozen other indigenous groups also call Darfur home, the largest of which are the Masalit and the Zaghawa. Darfur is home to Arab tribes, too, which are mainly pastoralist herders in the drier north and the savannas to the south, whose ancestors migrated to the region centuries ago. Together, they account for 40 percent of the population.

Neglected by successive Sudanese governments and stricken by drought, Darfur’s social fabric began to tear in the 1980s. The population grew fast, partly through a high birth rate but also because Saharan Arab nomads migrated to Darfur in search of land. The fragile coexistence of farmers and herders began to break down. Ethnic conflicts pitted the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa against Arab tribes. Violence escalated, culminating in the conflagration of 2003–5, which cost the lives of more than 300,000 people.

By 2009, intense conflict had subsided but peace was not in sight. High-level representatives from the African Union traveled throughout Darfur and spent 40 days in town-hall meetings, listening to the experiences, analyses, and complaints of the people. Members of all communities agreed that a complex tangle of disputes needed to be addressed, especially those relating to land and local administration. Local conflict resolution was required. The communities had a traditional mediation system, run by elders, which Darfuris agreed was still fit for purpose. The Sudanese government just needed to give the green light. But Bashir did not oblige. Instead, he played divide and conquer, fearing that united Darfuris would challenge his power.

Local conflicts were made more lethal by a second factor: the overspill of the decades-long Chadian civil war, which began in 1966. It intensified the following decade, when the Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi tried to annex Chad and, to that end, hosted and armed discontents from across the Sahara. In Libyan training camps, nomads calling themselves the Arab Gathering coalesced around a sinister plan to seize Darfur, drive out non-Arab peoples, and establish a Bedouin-Arab homeland. Disdaining international borders and scorning the pretensions of diversity and civilian rule, they nursed a toxic ethnic supremacism. They were the original Janjaweed, and their successors are, today, the soldiers, paramilitaries, brigands, and smugglers who are terrorizing Darfur.

Sudanese national politics also contributed to Darfur’s rebellion and its brutal suppression. Long-simmering resentment at Khartoum’s neglect of the region, and the way in which Bashir took the Arab side in local disputes, pushed its activists to take up arms. The Sudan Liberation Movement and the Justice and Equality Movement joined forces to launch devastating attacks on the Sudanese army in 2003. The army’s response was to mobilize the Janjaweed to strike back, pillaging and destroying any communities they suspected of supporting the rebels. Following a State Department investigation, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell announced that the Janjaweed had committed genocide.

Wester Eyes Aren’t Watching

Darfur was a rare case of an African crisis eliciting a passionate international response. Through a global advocacy movement, Darfur campaigners acheived their main goals. In 2007, a huge peacekeeping force, the UN-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), was mandated by the UN Security Council to protect civilians. The International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Bashir on ten counts, including three of genocide.

But peace did not come to Darfur. Talks—first headed by the African Union, then by Qatar with a staff of UN experts—reached deals that received the support of only a minority of the increasingly fragmented rebels. Khartoum blocked an African Union plan for an inclusive process of political reform.

Instead, the big questions were left unresolved. The displaced people stayed in their vast camps, which became de facto cities, fed by the World Food Programme. Darfur’s Arab tribes ruled the land, raiding with impunity, fighting each other and the militias over tribal boundaries and—most important—over who got to control the region’s lucrative gold mines. Hemedti emerged as the most capable Janjaweed commander. His family’s trading company expanded, and he profited from smuggling and guarding the border. Hemedti headed a transnational business-mercenary conglomerate, and became the chief employer of Darfuri youth.

Darfur was a rare case of an African crisis eliciting a passionate international response.

Over the objections of his generals, Bashir formalized Hemedti’s brigades as the RSF and brought them to Khartoum as his praetorian guard. It was a fatal error. In April 2019, peaceful civilian protestors surrounded the army’s headquarters, demanding that Bashir go. The dictator instructed his generals to crush them. In the generals’ late-night debate, Hemedti cast the deciding vote in favor of siding with the civilians. Bashir was overthrown. But the generals wanted power for themselves. Six weeks later the RSF dispersed the protesters with lethal force, killing more than 100. The civilians were not cowed. Hemedti and Burhan then agreed to talks convened by the African Union and Ethiopia, and backed behind the scenes by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States, which engineered a compromise. A turbulent military-civilian government resulted. As the cabinet wrestled with Sudan’s economic problems and the need to bring Darfur’s rebels into a new peace deal, Hemedti consolidated his businesses, expanded his forces, and strengthened his international networks. The RSF rented its services to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to fight in Yemen, and partnered with the Wagner paramilitary company.

Although Hemedti’s forces had murdered scores of civilians, he nevertheless presented himself as a champion of the people and the bulwark against the return of the cabal of soldiers and Islamists that had ruled Sudan under Bashir. Hemedti also positioned himself as a spokesman for Sudan’s deprived peripheries and as the broker of peace talks with Darfur rebels. In due course those rebels signed a peace deal—named the Juba Agreement—and returned to Darfur. The deal included ambitious promises of development, reform, and the integration of fighters into the army. In practice, however, it boiled down to political posts, jobs, and money for the rebels and their leaders. Hemedti hoped that they would join his coalition, but they distrusted him as an ambitious Janjaweed. The former rebel fighters’ return threatened Arab control of Darfur and sparked local violence.

This was the moment at which UNAMID should have enforced the Juba Agreement and kept the peace between the mistrustful armed groups. Instead, the UN, pressed by the Sudanese generals to wind down its operations, closed its mission in June 2021. A joint force of government soldiers, RSF troops, and former rebels was tasked with protecting civilians. Darfurians were aghast, but the UN appeared oblivious to the perils. It was an act of willful optimism that seems astonishingly misguided today.

Falling Towns

Under the Juba Agreement, a former rebel, Khamis Abubakar, an ethnic Masalit, became governor of West Darfur State. The local Arab militia was unhappy, and there was sporadic violence thereafter. But no UN mission came to investigate, sound the alarm, or dispatch political affairs officers to facilitate peace. The moment that fighting between the army and the RSF began in Khartoum on April 15 of this year, widespread violence also erupted in West Darfur. The spark for the conflict is not clear, but Arab militias began a murderous rampage against the civilian population. Army soldiers, outgunned and afraid, sheltered in their garrisons.

Survivors who have fled to nearby Chad describe RSF and Arab fighters going house to house in the regional capital of El-Geneina, killing, raping, and pillaging, leaving the corpses of men and boys to decompose in the streets. In May, paramilitaries attacked the city’s hospital and ransacked the sultan’s palace. In June, Abubakar denounced the violence as “genocide.” The next day he was abducted and murdered by armed men in RSF uniforms.

Darfur is without cellphone or Internet access, making it a black hole for information. But it appears that the RSF has also taken over Zalingei, the capital of central Darfur and the largest city of the Fur ethnic group. The militia commander has moved into the governor’s office. One by one, Darfur’s towns are falling to the RSF. The cattle-herding Arab tribes of eastern Darfur, which had tried to remain neutral in the earlier war, now find themselves with no option but to ally with the RSF. Rural aristocrats, whose writ once determined tribal policy, are now subject to the diktats of young militia commanders. Last month, nine senior chiefs declared support for the RSF.

So far, the most powerful of the former rebels—including Minni Minawi of the Sudan Liberation Movement—have stayed out of the fight. They fear the RSF, but they do not trust the intentions or the capacity of the army and have accused Burhan’s government of neglecting Darfur’s urgent humanitarian needs. Others have joined forces with the beleaguered army to defend key cities. How long the former rebels can stay neutral is uncertain, especially as the targeted communities need protection. Darfuri communities’ self-defense units urgently need international support to create safe zones in cities and displaced people’s camps.

The RSF has also swept across neighboring Northern Kordofan. Its conquest of the main city of al-Obeid was only thwarted by mass demonstrations by its residents. RSF paramilitaries are moving eastward to reinforce their fight for Khartoum, as trucks laden with the capital’s looted goods rumble in the opposite direction.

No Way Out

The Darfur crises—the still unresolved ethnic tensions and the Saharan Bedouins’ search for land and employment—are now driving the future of Sudan. Even if the Sudanese armed forces regroup and, with military assistance from its allies in Egypt and Turkey, manage to drive the RSF out of Khartoum, the government has no solution to the problems ravaging Darfur.

Neither does Hemedti. The RSF struck fierce early blows in the battle for Khartoum and has held its ground against a heavy counter-onslaught. But whatever support Hemedti may have had among the population has been destroyed by the behavior of his soldiers, who have killed and raped, ransacked residential neighborhoods, taken over hospitals, and desecrated cultural sites and civic buildings.

As Sudan burned, Hemedti disappeared from view. For a populist leader reliant on projecting his personality and setting the political agenda, this silence was surprising. His invisibility fueled rumors that he had been seriously injured. On July 28, he released a video in which, stiff and pallid, he spoke for 20 seconds to lay out his peace terms. Since then, he has released audio recordings, but he has not been seen. There are signs that he is losing his grip: RSF units in parts of Darfur have begun to divide along tribal lines and fight one another.

Meanwhile, the Sudanese are learning what Janjaweed governance is like. It is rule from the saddle: violent and venal. It relies on tribal solidarity, racism toward darker-skinned people, and disdain for institutions and laws. It involves robbery on a massive scale, which will likely stop only when there are no more cities left to loot.

The UN’s 2021 actions in Darfur had a willful optimism that seems astonishingly misguided today.

There is no sign of a serious international effort to resolve the crisis. Only halfhearted mediation efforts have been made, and they concentrate solely on stopping the fighting in Khartoum. None has made progress or paid attention to Darfur.

Twenty years ago, the United States was active; today it is absent. The first sign that Washington’s disinterest might be shifting came when the U.S. ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, visited Darfuri refugees in Chad earlier this month. But beyond imposing sanctions on RSF leaders and supporting humanitarian efforts on the border, the United States appears to be at a loss for what to do. The UN, which has the authority to act, is waiting on the African Union, which is doing next to nothing.

Far greater resources and political will—albeit much of it misdirected—did not solve the previous war. This time it is going to be tougher. But there is one promising factor: there are no geostrategic stakes in Darfur. All sides should have an interest in stopping the bloodshed. Countries that are at odds over other global issues should be able to set aside their differences and agree on actions to protect civilians, provide essential aid, and stop an unfolding calamity that will likely surpass what Darfur suffered two decades ago. When the UN General Assembly meets in New York this week, African leaders will gather on the sidelines to discuss Sudan. This is the opportunity for them, and the UN, to show that the agendas of peacemaking and civilian protection are still alive, and for the United States to put its weight behind a serious reengagement with Darfur. It is the least the long-suffering Darfuris deserve.