There’s a lot of bad analysis around the current “world food crisis” and the purported threat of “Biblical famines” globally. The World Peace Foundation program on mass starvation clarifies.

Last year, UN Secretary General António Guterres cited figures of 276 million people worldwide who were food insecure and an increase in food prices to warn of “multiple famines.” His solution: “stabilize global food markets.”

It’s essential to distinguish between chronic hunger and famines. A famine is an exceptional case of extreme hunger causing widespread death from starvation and related causes. Historical famines are usually measured by numbers of excess deaths, ongoing ones by a cluster of indicators of food insecurity, malnutrition and mortality.

Famine and food security have three component parts.

First is food availability. Scholars of famine have shown, time and again over the decades, that food availability decline is neither necessary nor sufficient for famine. But commentators and policymakers still persist in the rudimentary error of shouting “famine!” when there’s a decline in food production or delivery. The latest example was the interruption in grain shipments from Ukrainian ports. Definitely a crisis—but not a direct cause of famine.

A good indicator of food availability is prices. Staple food prices have been rising for the last three years—hitting a peak level of 171% of recent index level a year ago. But basic foodstuffs are still cheaper today than at most times in the 20th century.

The second element in food security is food entitlement—the ability of poor people to buy food. With economic crises rippling around the world, unemployment is up and wages are down. The World Food Program puts the number of food insecure today at 345 million, a big jump from last year.

But we still hear economic policymakers celebrating wage freezes or cuts as a sign of success in controlling inflation and keeping food affordable. Keeping food prices stable is meaningless if people don’t have money to buy it. That’s true not just in America and Europe but across the Global South, where rising interest rates threaten a new debt crisis and ultra-austerity.

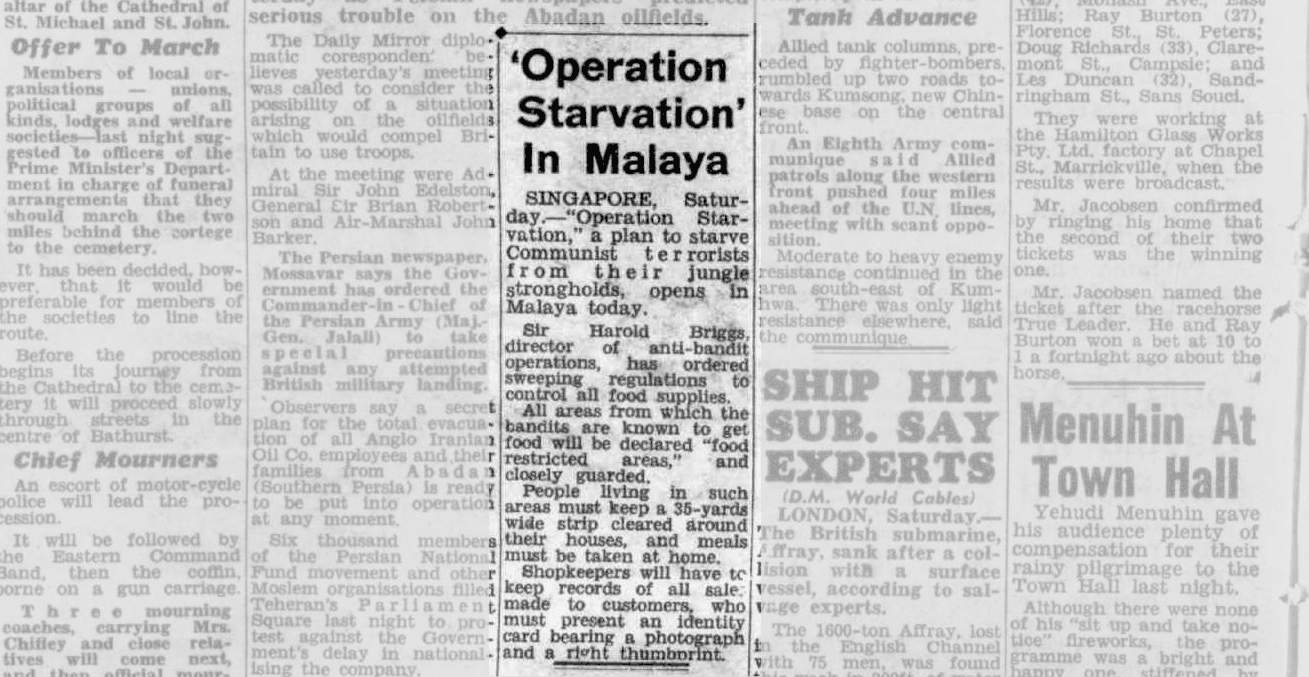

The third element in famine is starvation as political or military decision. The World Peace Foundation’s ‘famine trends’ dataset shows that great majority of modern famines have been caused by starvation crimes in war or the recklessness of dictators and generals who pursue their goals well aware that mass starvation will follow. To people subjected to pillage and siege, it doesn’t matter how much food there is in the world, or its price, or how much money they have in the bank. Someone in power is starving them with impunity and that’s what counts. The history of the last 150 years shows that when governments stop perpetrating famine crimes, famines stop. We strongly advocate for accountability for starvation crimes. A typical world leader’s speech about global hunger and famine begins by mentioning all three factors—food supply, poverty and conflict-related food insecurity. But when they get on to action, it’s only food production, transport and price. That’s the easy part because governments and corporations agree these problems to be fixed—they only quibble about the details. If we’re stop famine, world leaders need to deal with the hard stuff: food entitlements, living wages, and ending impunity for starvation crimes.