In previous blog posts I have made the argument that the dominant logic of power today is power-as-commodity. I also argue that formal institutional power—the established organs of state and mechanisms of communication—has become subordinated to kleptocratic logic.

I have also suggested that ambitious political entrepreneurs are mounting a constitutional coup to unleash unlimited money-making to set up and run mechanisms that shape our thinking in the future. At the center of this is a race to dominate the new world of AI.

That’s not the whole story. There’s a third logic of power at work. It’s the oldest, the original mode of power—’wild power’. It comes in different forms. And each has its theory of violence, including one a theory that violence, at scale, can be its own legitimation—that might becomes right.

To follow this logic, we need to see state formation not as a general sociological law but as something that happens in a particular configuration of historic circumstances. It’s hard to break out of this intellectual confinement. It helps to have lived and worked in places such as Somalia, it requires astonishing intellectual contortions to argue that there’s anything like ‘state formation’ going on. This is how I began my Somalia chapter in The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa:

There are more cogent explanations for what appears to be ‘anarchy’ other than decrying nihilism, disorder and the absence of a working state. That doesn’t make this state of affairs desirable—not in the least—it’s just a description of how power works.

Nonetheless, in our Enlightenment canon, every influential theory of power and politics is subsumed under a theory of the state. That’s a huge oversight. Power also exists ‘in the wild’. There have been many societies in which power is exercised without anything resembling a state. Indeed there’s a strong argument—made by David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything—that Enlightenment ideas of democracy and liberty were derived from the actual practices of Native American political systems, which didn’t possess states.

Wild power appears in different modes. There’s the politics of peoples without rulers, as described by many of the pioneer social anthropologists whose writings inform Graeber and Wengrow’s book. There are communities reachable, but not graspable, by states and empires, whose social systems are mobile or deliberately unintelligible to outsiders—what James Scott calls the arts of not being governed. There’s the politics of everyday resistance, what Scott calls the weapons of the weak.

In each of these modes of wild power, violence has roles. It can serve to deter an outsider and defend autonomy, to preserve a social order or ethic dedicated to resistance. Like some languages and social mores, practices of violence may be designed to be untranslatable.

There’s also the lawlessness of the colonial frontier, including the heroic ethos of the pioneers who live by their wits, weapon in hand, beyond the grasp of the state to which they nominally owe allegiance. Metropolitan rulers treat their licensed servants warily—they can be ‘martial tribes’ conscripted as frontier police, or privateers and buccaneers who are the vanguard of conquest. Those governors have good reason to worry—it’s best to keep a close eye on specialists in violence.

The great medieval sociologist Ibn Khaldun saw history as a cycle in which metropolitan dynasties preside over cultural glories (hadhari) but also, over a span of a few generations, suffer from political decay, until a new political force, animated by primordial solidarity (‘asabiyya) sweeps in and installs a new warrior leader on the throne. We can see this as the clash between institutional power and wild power, between state-building and heroic violence.

Great conquerors such as Jinghiz Khan—the original Mogul—and Tamerlane, are exemplars. These men were practitioners of heroic violence, their legitimacy proven by the scale of their massacres, their legacy manifest in a new civilization that defines its own rules.

These aren’t historical curiosities. Eric Voegelin, whose writings have cult-like status among many on the Christian nationalist right, wrote about these phenomena, and his followers celebrate with the bastardized slogan, ‘God, like fortune, loves the strong man.’

How could someone like J.D. Vance, formerly a declared critic of Donald Trump, become a convert while retaining his core beliefs? This lineage of thought can help us understand.

For two millennia, religious zealots from Judaism, Christianity and Islam have believed that their devotion, expressed in acts of holy violence, will prompt providential intervention and a new cosmic order. Counter-enlightenment political projects in 20th century Europe were infused by reinterpretations of these traditions of heroic violence. Similar thinking colors Kananist ultra-Zionists, Christian Zionists, and apocalyptic jihadis even today.

In a less mystical way, the United States is unique among today’s developed countries in that its frontier ethos remains a vibrant strand in political culture—arguably its most vibrant strand. It’s manifest in the passion for Second Amendment rights—gun ownership symbolizing refusal to defer to the strictures of authority. It’s evident in the resonance of narratives that portray the ‘deep state’ as a conspiracy to impose order on ‘real’ Americans who believe that the law rightfully belongs in their own hands.

The alt-right and the tech moguls believe in disruption in principle. In shaking the existing order, something better is bound to emerge.

Some neo-reactionary advocates—such as Curtis Yarvin and Nick Land—take Carl Schmitt’s dictum that the sovereign is the one who determines the exception a stage further, to make the sovereign literally untamable, perpetually above the reach not only of law, but of order.

It’s notoriously difficult to theorize violence—it’s an act, an experience, and a communication. Each of the logics of power—commodity power, institutional power, wild power—utilizes organized violence in different ways. Institutional power is concerned with regulating and legitimating violence—ideally, making state violence invisible and criminal violence abhorrent to all. This is the Weberian formulation of power. Commodity power is concerned more with the utility of violence, in the way that the heads of criminal cartels calibrate their killing and coercion. Kleptocracy possesses a collusive logic of violence.

Each variant of wild power frames acts, experiences and communication of violence differently. For example, acts of violent resistance can be communicated as acts of emancipation—as Frantz Fanon articulated.

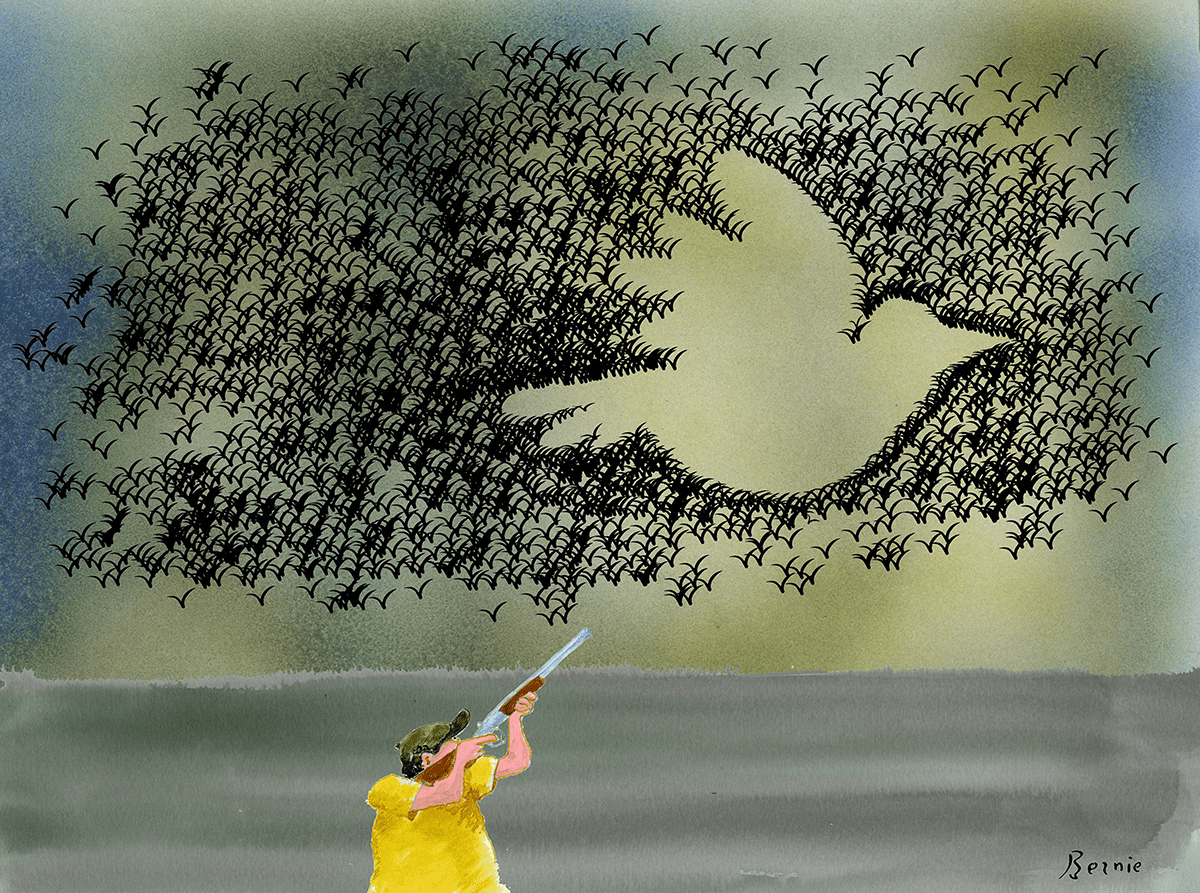

Our main concern is sovereignty-seeking wild power. It’s the greatest threat. Some of its adherents value violence as such. They hold not only that acts of revolution or conquest can in due course be self-legitimating, but they take it a stage further and advocate entrusting themselves—and everyone else—to the logic of violence and see where it leads.

In the next post I will bring together the three logics of power and violence asking how they interact to drive World War X.