Every day we read that we live in an age of disorder. But what does that mean? Are our intellectual tools for ordering the world just not sharp enough?

In my essay ‘No End State: Exploring Vocabularies of Political Disorder,’ I try to clarify what we might be talking about when we talk about disorder in society, politics and global affairs. I suggest that there are at least give different kinds of disorder, each of which deserves its own analysis.

First is lawlessness, exemplified by the barbarians outside the gate, such as the nomad, the pirate or the outlaw. Such groups represent the antithesis of the orderly state—yet in history they have often been fundamental to state-making, from the Mongols of central Asia to the frontiersmen celebrated in contemporary America. Second is chaos, the character of a system too complex to be modelled accurately. Within this category of chaos there is risk generated by the triumphs of modernity: our own institutions and technologies have become so complex that those who design them may not understand them. Next is incommensurability: the incomplete legibility of an unfamiliar system. Because translation always contains an element of indeterminacy, this isn’t just a question of seeking a deeper underlying order—there is at least a residual element of uncertainty. Fourth is disorder by design: the strategies adopted by rulers to prevent organized opposition from emerging. Last is revolutionary disruption, once a preserve of the radical left but recently appropriated by the political right.

I go on to identify four processes of disordering, namely calamity, violence, markets and democracy. Of these, the most intriguing is the last: possibly, disruption is a fundamental character of democratic power, subverting of any entitlement to rule on the basis of social order.

Western nations have been relatively protected from disorder, and the western academy even more so. There is much to learn from societies on the margins of global power relations, where the workings of disorderings can be seen in their most raw forms.

The essay explores what it might mean to bring concepts of disorder in from the margins of political-economic theory, dethroning the ordered institution as the analytical center of the political science episteme. This is not a theorization of disorder, but the preliminary task of exploring a vocabulary which could allow us to talk sensibly about the varieties and logics of disorder.

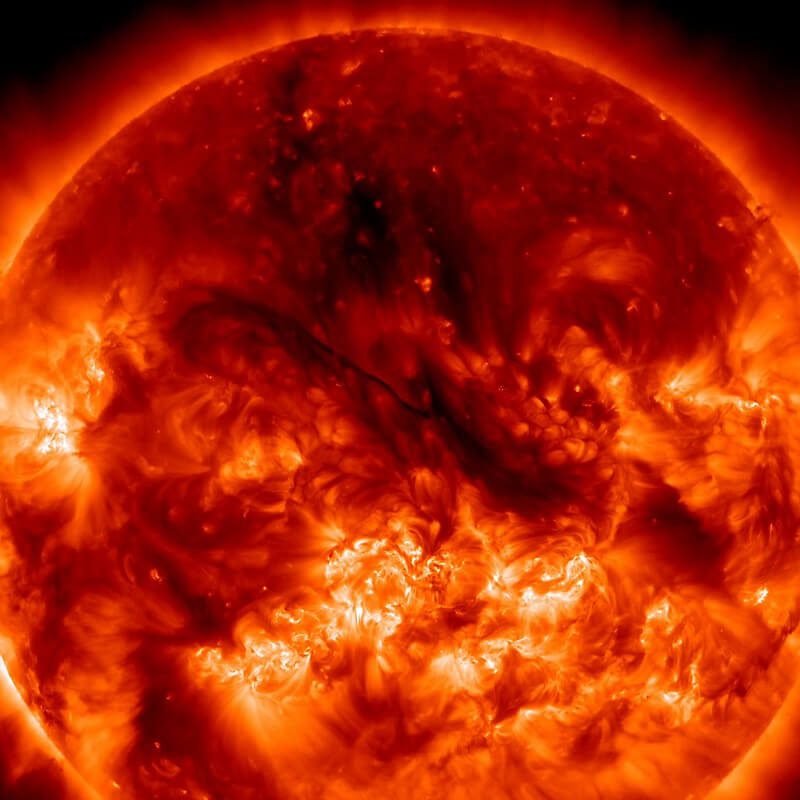

Photo: Amazing Filament, Solar Dynamics Observatory, NASA, August 7, 2014 (CC BY-NC 2.0)