Essay published by openDemocracy, May 24, 2016, as part of a special series in conjunction with the publication of a report by the Human Security Study Group at the LSE, which is convened by Mary Kaldor and Javier Solana, entitled From Hybrid Peace to Human Security: Rethinking the EU Strategy Towards Conflict.

Almost all of Europe’s maritime trade with Asia passes within a few miles of the coast of the Horn of Africa, in particular the narrow straits of the Bab al Mandab, where the tiny African country of Djibouti is separated from Yemen by less than 30 kilometers of water.

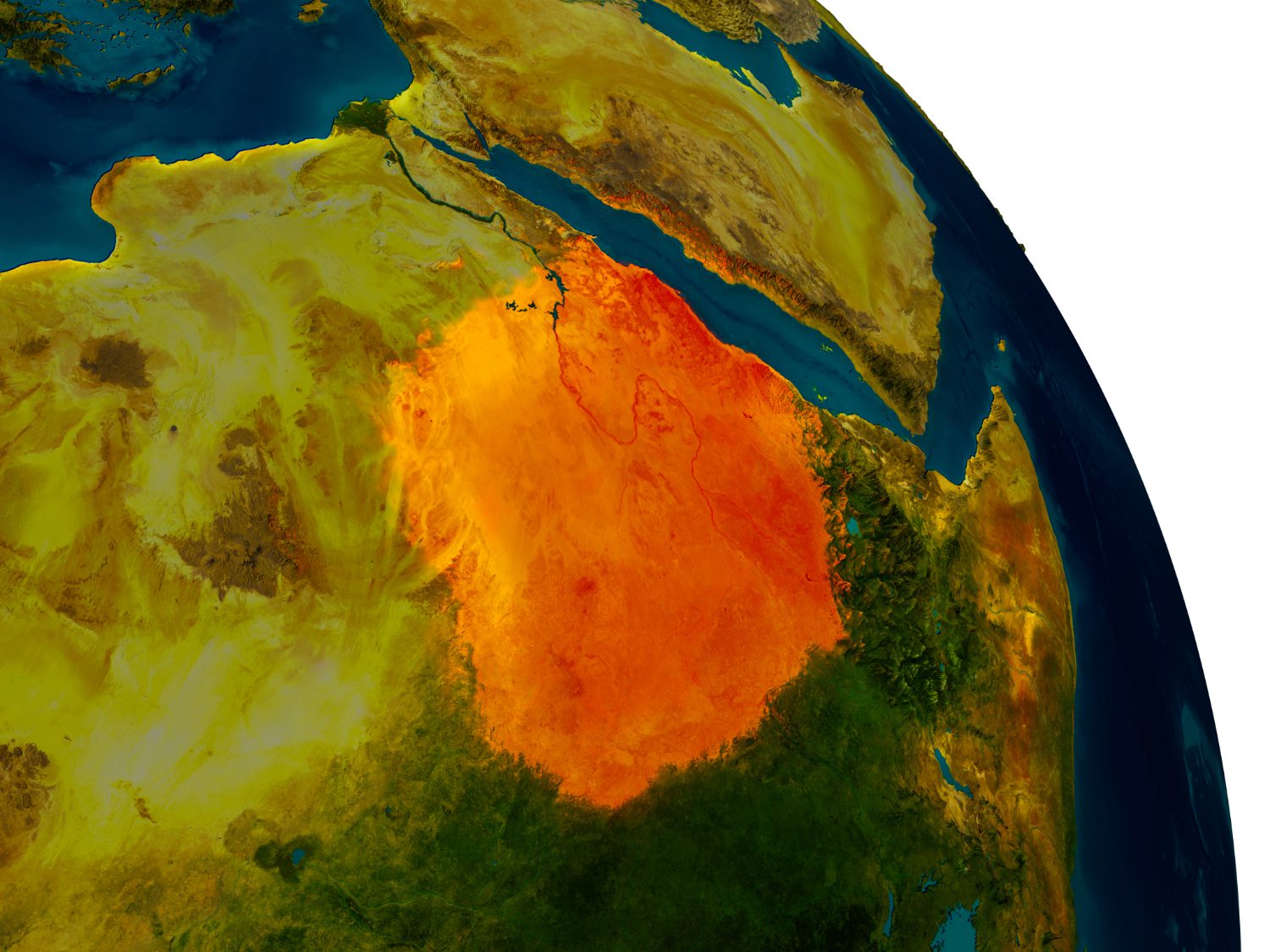

The Horn of Africa — which also includes Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan — has never historically defined itself as a region. It is diverse in physical and human geography, with extraordinary linguistic diversity, and with equal numbers of Christians and Muslims. Its peoples are linked to Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean — and more recently to Europe and America. But they rarely convene as the people of the Horn. Rather, the Horn of Africa has been defined by outsiders, particularly the world’s great powers, as a region that spells trouble.

Main artery

The Horn’s liability is its location. When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, the Red Sea became one of the world’s main arteries for commerce. Its southern reaches were briefly threatened a decade ago by piracy off the Somali coast. Today there’s a much more serious peril: Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsular controls a stretch of the coastline of the Gulf of Aden. We have yet to see what maritime terrorism will do for insurance rates for shipping.

Meanwhile the Saudi Arabia-led coalition of countries intervening in the Yemeni civil war are rushing to secure their military and political flank in Africa. In doing so they are shaking the already-fragile security order in the Horn of Africa — notably by pouring money into Somali factions and bringing Eritrea out of isolation by equipping military bases there. There are real risks of renewed war, notably between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Violent extremism

Alongside maritime security, two other issues are thrusting the Horn onto Europe’s political agenda. One is violent extremism: the Somali militant group Al-Shabaab is not only a threat to the people of the region, but far beyond. In response, the African Union has deployed a counter-insurgency operation dressed as a peacekeeping force. The African Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is largely funded by the EU: the single biggest European security expenditure on the continent. And while they fight terrorists, Saudi Arabia and Qatar also fund the spread of their intolerant, extremist version of Islam, Wahhabism. Traditional, tolerant Sufi forms of Islam are on the retreat in Somalia and Ethiopia. Where Wahhabism penetrates, militancy follows.

Migration expertise

The second issue is migration. Behind Syrians and Afghans, Eritreans fleeing their despotic government are the third largest group of refugees arriving in Europe today. Out of desperation, the EU has started to overcome its scruples and provide development aid to Eritrea—though its clear that spending aid money on that country’s electricity infrastructure isn’t going to change the circuits of political power, and so is most unlikely to stop the exodus.

It’s a typical ‘do something!’ reflex rather than a considered policy. And Europe needs to be aware that the Horn hosts many, many more refugees and migrants than ever make their way to the shores of the Mediterranean. Ethiopia alone has more than 700,000 refugees, and it provides free secondary education to them. Europe’s panic over distress migration needs to be tempered by the knowledge that African countries are doing far more — and also know far more about what works in dealing with this problem.

Where is the EU?

The Horn is on the cusp of becoming a strategic hard security issue for Europe. And not only Europe: China is building its first overseas military base in the enclave state of Djibouti, within sight of the procession of container ships that carry the greater part of Chinese exports to Europe. Saudi Arabia is constructing a Red Sea fleet. Iran and Russia are both interested.

Despite the activism of the EU Special Envoy for the Horn, Alex Rondos, a coherent EU policy is not yet within grasp.

Until recently, the Horn of Africa has been, for Europe, a region for engagement on issues such as poverty reduction and humanitarian action, conflict resolution and democratization. Policies and programmes have been well-meaning, but have had modest impacts. This is human security-lite: fragmented and inconsistent in accordance with disparate objectives. The risk is that the EU will transition from an ineffective human security policy to an ineffective hard security policy, and end up with neither.

But, approached rightly, Europe can have both, and the Horn can benefit. Indeed, a combination of a top-down approach aiming at preventing wars, and a bottom-up approach framed by the people’s issues, is the best chance for progress.

One talking shop we could do with

Starting at the top, one of the most striking things about the Horn and the Red Sea is that there is no regional organization that can grapple with its security challenges. The African Union does not cross the Red Sea. The InterGovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) includes the countries of the Horn, but not Egypt — an historic powerbroker, with strategic interests in the Nile and the Red Sea — and also is confined to the African shore. The Arab League is not effective, which is one reason why the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has taken the lead in the Yemeni intervention, and is using financial muscle to win African countries to support its operations, rather than multilateral diplomacy. Ethiopia, the pivotal state of the Horn, is landlocked and keenly fears being surrounded by hostile states backed by historic rivals such as Egypt.

In the absence of any Red Sea forum or similar peace and security mechanism, the EU can play a role as convenor of the overlapping multilateralisms of the various regional organizations that between them could provide the needed forum for defining and addressing the region’s problems.

It is the simplest of beginnings: a talking shop. This leverages the EU’s principled and strategic commitment to multilateralism; it distinguishes the EU from other western approaches that have been to project power and vanquish enemies rather than build peace. It also distinguishes itself from the dominant security strategy in the Middle East, namely ‘coalitions of the willing’ that engage in military deterrence and force projection. This can build on the real opportunities that exist in the Horn, namely the African Union’s hard-won norms and principles of resolving conflicts through political means. Can this deliver peace? It cannot do so alone, but without such a mechanism, the chances for durable peace are remote.

Pluralism and tolerance

The human security dimension is equally important. This is a long and complex agenda including a host of issues from human rights to the environment. It directly intersects with two of the EU’s main strategic worries — migration and violent extremism. Only with better prospects for human development, will young people be ready to stay in the region rather than seek a better and freer life in Europe. Only with a reinvigoration of the values of pluralism and tolerance will the apparently relentless spread of Wahhabism among the region’s Muslims be reversed.

What knits these issues together, and where the EU has a unique advantage as an external partner, is the need for an integrated regional approach. The countries of the Horn and their immediate neighbours in the Arab world possess all the potential of a richly variegated region. The huge differences in togography, climate, natural resources and human capabilities across the region mean that, better integrated, each country has valuable comparative advantages. Ethiopia’s national security strategy, founded on the ‘economy first’ principle of promoting economic growth and poverty reduction, while tying Ethiopia more closely to its neighbours through transport and power infrastructure, provides a foundation on which to pursue this.

Reviving neglected commitments

Meanwhile, a formerly vibrant agenda of popular engagement with peace and security issues has stalled. The African Union was established in 2000 riding a wave of popular demand for democracy, peace and unity. Its foundational principles are strongly democratic and its declarations and protocols (such as in Tripoli in 2009) repeatedly affirm the importance of academic freedom and civil society participation in Africa’s peace and security mechanisms. In 2005, IGAD adopted a regional security strategy document with major inputs from civil society organizations, which affirmed that promoting regional security was coterminous with the progress of democratic participation.

These commitments, solemnly adopted, have been neglected: now is the time to revive them. There is nothing comparable across the Red Sea, where the GCC is essentially a club of autocrats. The EU has the rationale it needs to place itself in the middle of this tri-continental conversation, and to contribute to both the hard security and the human security of the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea.