Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, known as ‘Hemedti’, attracts a horrified fascination. A man of humble origins, who rose through military prowess, has a great city at his mercy. His story evokes great historical antecedents such as the Turko-Mongol conqueror Timur (1336-1405). Timur led an army of nomads that conquered Persia, captured and sacked Delhi, defeated the Ottoman Empire, overran Baghdad, Aleppo and Damascus, and turned to invade China, failing only because of his death from illness.

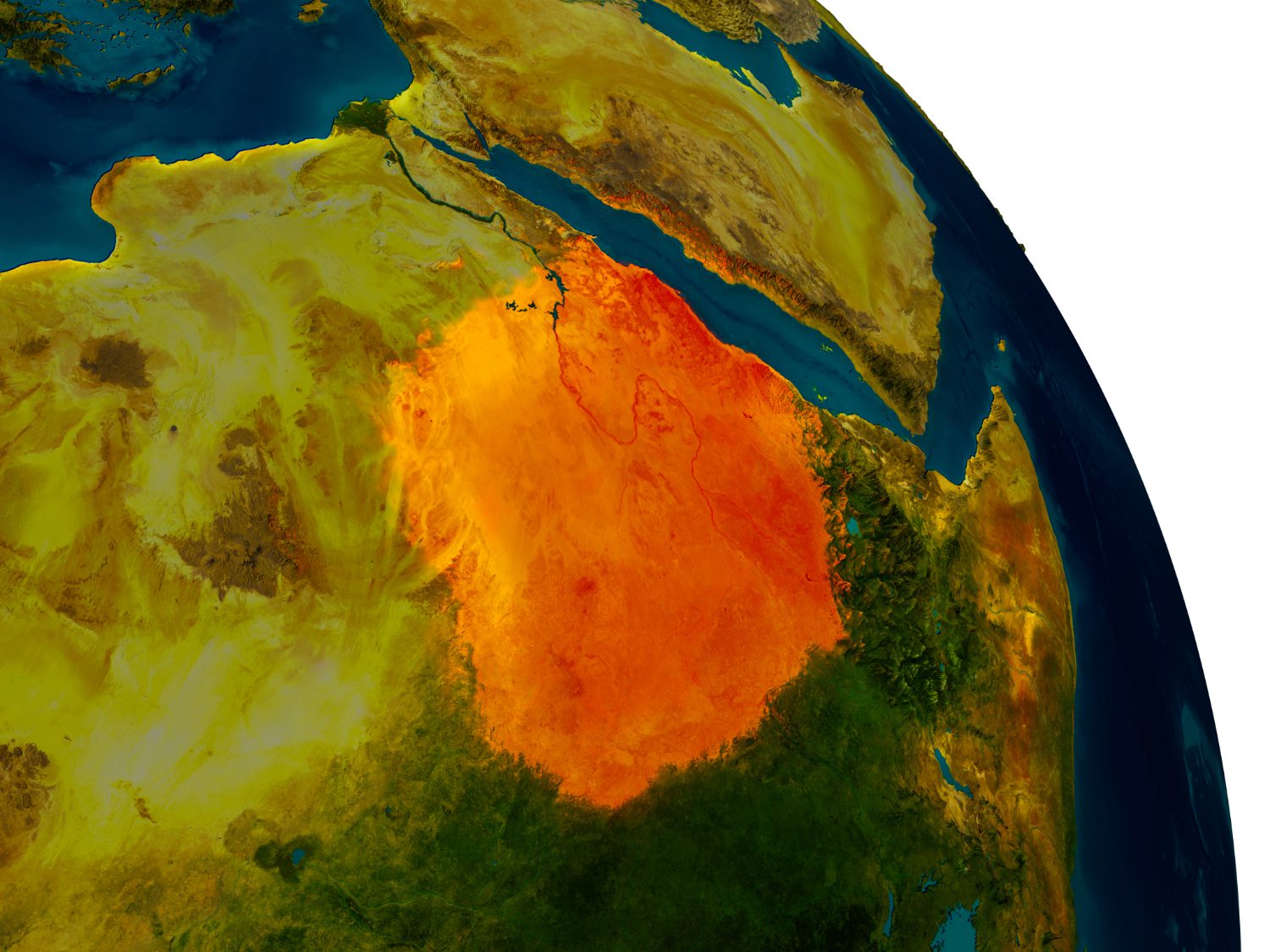

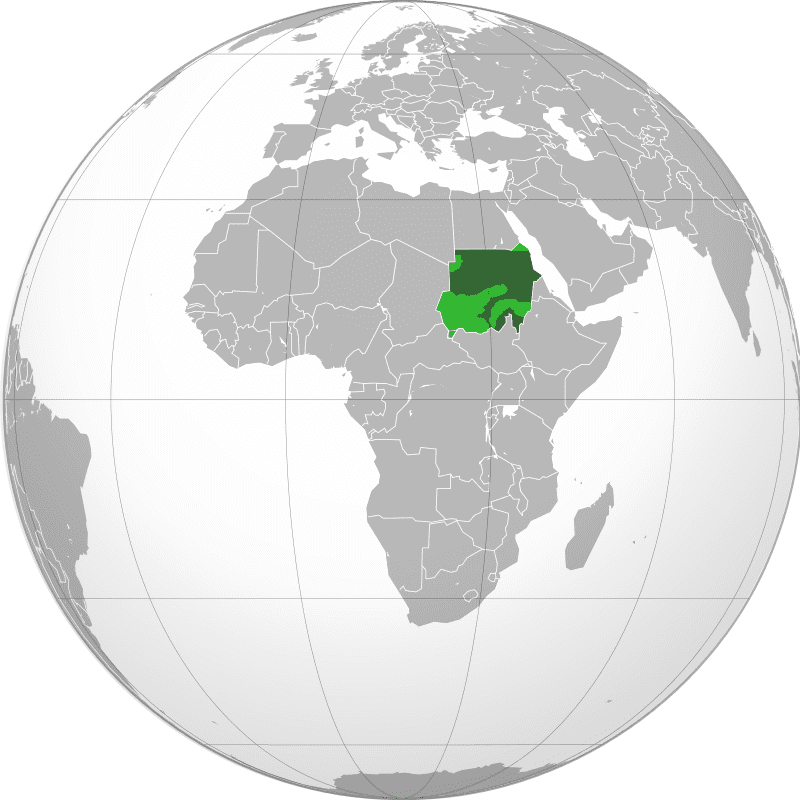

Sudanese have begun talking of Hemedti’s ‘Republic of Kadamol.’ The scarf that covers the face is called kadamol, and from the Atlantic shores of the Sahara to the Red Sea, it is the ubiquitous dress of the desert nomad, keeping wind-blown sand and dust out of one’s mouth and nose.

While Timur laid siege to Damascus, the famous scholar Ibn Khaldun was lowered by rope from the city walls to make his way to Timur’s camp to parley with him. Ibn Khaldun wrote a vivid account of those events, detailing his debates with Timur, the Mongol army’s breaching of the city’s defenses, and its subsequent plunder and burning of the city and its great mosque. Ibn Khaldun also recounts the odd story of his mule, which the conqueror asked to buy, the scholar thought it advisable to offer as a gift, and for which Timur later sent payment. One doesn’t haggle with a man who killed 17 million people. Timur reputedly left piles of skulls at the gates of cities he had ransacked; in the case of Damascus he appears to have stopped short of that conspicuous barbarity.

Ibn Khaldun described the destruction of Damascus and its Great Mosque as ‘an absolutely despicable and abominable deed’. He immediately qualified this with the words ‘but the changes in affairs are in the hands of God.’

Timur’s conquests were, for Ibn Khaldun, an exemplary case of the triumph of asabiyyah—the spirit of group solidarity, found in its purest form among nomadic clans—and how it could vanquish a decaying dynasty. In his masterpiece, al-Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun casts the history of civilization as a cycle in which metropolitan dynasties preside over cultural glories but also, over a median span of three generations, suffer from political decay, until a new political force, animated by primordial solidarity, sweeps in and installs a new warrior leader on the throne.

It is not difficult to see Hemedti, and his army representing asabiyyah overrunning a decayed body politic of a Sudanese state that had failed to believe in itself.

Timur’s influence on western European political thinking was profound, though rarely recognized. By diverting the Ottoman armies to their eastern frontier, Timur was seen as the unheralded savior of western Christendom. In Kit Marlowe’s play Tamburlaine the Great, he is portrayed as the godless ‘scourge of God’ and the prototypical world-conqueror of unbounded ambition. More profoundly, Timur was also a devastating—and revealing—example of brute power replacing the transcendental order of existence, in which church and state were fused.

Nowhere in The Prince does Nicolo Machiavelli mention Timur. The connection was drawn by Eric Voegelin, for whom Timur provided the single most compelling image of the prince creating a principality by the force of his own skill in arms, ruling by laws of his own creation. The order of this new polity lay beyond good and evil, simply in what is enforced by its prince and experienced as real by its subjects. Timur’s political theology anticipated Friedrich Nietzsche—as seen in Marlowe’s infamous (and factually false) depiction of him not only as a Pagan but as a destroyer of the Quran.

Voegelin was interested in how the Timurid Empire endured, its ‘representative Cosmic order’ aspiring to perpetuity. He compared it with mid-20th century Communism. Hemedti isn’t likely to do anything comparable, though he is part of a world-wide trend of politics untamed by norms and institutions—the ‘wild power’ of the frontier staking its claim on the metropolis. Sudanese rulers’ hubris was to formalize that frontier within the state and hope to remain its master, not its victim.

For every revolution that history records as creative destruction, there are many that are just destruction. The ‘give war a chance’ school, drawing on a simplistic reading of Charles Tilly’s maxim that in modern Europe, ‘War made the state, and the state made war’, overlooks the brute fact that, most often, war breaks states. Hemedti’s political norms answer to nothing higher than the group solidarity of the disaffected lumpenmilitariat and the myopic greed of his commercial partners and patrons. It tears down the façade of civic rules at home and multilateral principles abroad.

It’s not likely that Hemedti has read Machiavelli but he doesn’t need to. He knows how to do wrong according to political necessity, how to maintain the appearance of a virtue while practicing its opposite, how to engender fear as required. The flaws of President Omar al-Bashir and General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan are to have relied on the military services of auxillaries and mercenaries (who, if capable, are untrustworthy, and if incapable, are useless). They too ruled by the book of Machiavelli, and they failed—al-Bashir hated more than he was feared, al-Burhan despised more than he was feared.

On the failings of the civilian-led transition, we can do no better than to quote from Chapter XIV of The Prince:

A prince ought to have no other aim or thought, nor select anything else for his study, than war and its rules and discipline; for this is the sole art that belongs to him who rules… Because there is nothing proportionate between the armed and the unarmed; and it is not reasonable that he who is armed should yield obedience willingly to him who is unarmed, or that the unarmed man should be secure among armed servants. Because, there being in the one disdain and in the other suspicion, it is not possible for them to work well together.

Hemedti has dealt a probably lethal blow to the rotting edifice of the Sudanese institutional state. But he has a bigger significance. He and his backers show that there can be no coexistence of wild power with the rule-governed multilateral order, that was the work-in-progress of the UN agenda for peace and the Pax Africana. If Hemedti prevails in Khartoum—and it’s still very uncertain whether he can do so, or whether there will be a Khartoum at all—he can thrive only if others of similar ilk wield power across the wider Sahara-Nile Valley-Red Sea region. That is the Republic of Kadamol in spirit if not in law.

Meanwhile the world’s diplomats and international civil servants appear like the bewildered Damascus dignitaries who accompanied Ibn Khaldun to make their futile supplications to Timur, and who ended up scurrying away for safer cities, their worldly goods plundered by brigands on the road.

Photo: Desert man with head scarf, Savvas Stavrinos | RGBstock.com