On November 4th, 2020, the Ethiopian government and its allies launched a full-blown offensive, which marked a key event in unleashing of genocide on Tigray. These allies include armies from the neighboring states of Eritrea, regional forces, and militias from across Ethiopia, primarily the neighboring Amhara region, and have been bolstered by weaponry obtained from China, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

From the onset, the war was characterized by indiscriminate and wholesale attacks against the civilian population of Tigray. The atrocities committed by Ethiopian and allied forces amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and acts of genocide. The roster of brutalities is lengthy and has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands, the displacement of millions, and the total destruction of essential civilian infrastructure and services. A particularly gruesome defining feature of the ongoing war against the people of Tigray has been the extensive weaponization of rape and the widespread prevalence of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV).

The pattern of weaponized sexual violence unleashed on Tigray during the war is consistent with the well-established definitions of CRSV. As is established by these definitions, perpetrators are affiliated with a state or non-state armed group and the victims are most frequently perceived to be members of a persecuted group, such as a political or ethnic minority.

Far from being an inevitable by-product of war, CRSV is a crime under International, Criminal, and Human Rights Laws. CRSV is a global phenomenon that has long affected people from across the world. As the Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict database shows, since the early 1990s, CRSV has been recorded in places such as Myanmar, India, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Perpetrators of CRSV in Tigray were state armed groups and their proxies, including Ethiopian, Eritrean, and regional Amhara forces. These attacks were directed against the Tigrayan people, an ethnic minority in Ethiopia, and took place in a climate of impunity precipitated by a war declared by the Ethiopian federal government. Women and girls, as well as boys and men in Tigray, have been subjected to rape, often perpetrated by groups of armed men. There have been numerous reports of sexual slavery, with women and girls held captive for days or weeks. Survivors have been told during the course of these attacks that the perpetrators seek to impregnate them, with the intent of eliminating the Tigrayan bloodline. Moreover, instances of extremely violent and brutal enforced sterilization by armed groups have been reported. The scale of the CRSV in Tigray is staggering both in its magnitude and brutality. Per the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the acts of sexual violence against Tigrayans were committed with the intention to make the target group infertile, cleanse the bloodline, and erase identity as indicated by the perpetrators fit the definition of genocidal rape.

The most conservative estimates using the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) commonly used by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) indicate that more than 26,000 women and girls will seek clinical care for SGBV in Tigray. It bears noting that while this calculator is very efficient for planning when it is used for natural and other emergencies it does not take into account situations in which sexual violence is deliberately used to terrorize, dehumanize and devastate communities, as happened in Tigray.

The full extent and magnitude of sexual violence in Tigray are not yet known because the Eritrean, Ethiopian, and allied forces impeded access to services, by threatening and killing service providers such as medical service providers, destroying health services as well as threatening survivors who tried to access services. However, with all the impediments the number of survivors that have accessed health services in less than 6 months has significantly downsized.

Given the near-complete destruction of the region’s health infrastructure and the collapse of reporting mechanisms, this number is most likely a significant underestimation. As shocking as these numbers are, they do little to capture the brutal and sadistic nature characterizing CRSV in Tigray. The attacks often took place in full view of people’s families, with children present, and were accompanied by physical as well as psychological torment. Sexual violence was also utilized as a tool of ethnic cleansing and genocide, designed to terrorize, humiliate, and dehumanize the entire Tigrayan community, using people’s bodies as battlefields to do so.

CRSV survivors have to grapple with numerous challenges in the aftermath of such attacks, including physical and psychological trauma, stigma, and denial. Survivors of weaponized sexual violence in Tigray, who have been denied access to sexual and reproductive services including post-rape care as a result of the humanitarian blockade imposed by the Ethiopian government, are especially vulnerable to these effects.

Double Victimizing Survivors

The agony however did not stop there. Survivors are further victimized by institutions that refuse to take their account with sufficient seriousness or disbelieve it altogether. In a leaked audio of UN representatives and chiefs of mission in Ethiopia, participants are heard sanitizing, rationalizing, and discrediting the voices of survivors of the genocidal rape in Tigray. The participants went further to discredit the testimonies of service providers by denying the fact that the safe house was raided. Alarmingly, a UN official participating in the meeting referred to the reports of CRSV as “media hype.” Former Minster of Ministry of Women, Children and Youth, Filsan Ahmed, disclosed in an open letter an instance when a UN representative remarked “the rapes are an exaggeration of the TPLF” when her office published a report documenting weaponized rape in Tigray by Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers.

Although some of the officials have been recalled following the audio release, international institutions’ continued action (or lack thereof) is reflective of systemic defiance of humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. The denial, downplaying, and outright erasure of victims have also been deployed by the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments, their social media networks, and state media in a coordinated disinformation and propaganda campaign, to a shocking degree.

Disputing the Numbers and Victim Blaming

When reports of the weaponized rape became beyond anyone’s ability to deny, the Ethiopian government resorted to disputing the numbers and systemic nature of the act. Gedion Timothewos, Federal Minister for Justice, in a press briefing claimed “cases investigated show deliberate exaggeration and campaign of disinformation.” As an extension of this minimization of the widespread of weaponized rape, Gedion also claimed that 25 Ethiopian soldiers were charged with committing acts of sexual violence and rape. Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopian Prime Minister, has also alleged exaggeration.

There has also been a campaign of false allegations and fabricated narratives targeting and accusing survivors, health professionals in Tigray and non-governmental organizations dedicated to helping the civilian population. These are systematically disseminated through government-operated and affiliated mass media platforms and on official social media pages with large viewership. It is estimated that more than two-thirds of the entire population who do not have any or regular access to the internet rely on these platforms as their primary source of news and information.

A particularly repugnant example of this campaign of disinformation was an interview on state media claiming to have evidence that survivors of CRSV that have come forward with their testimony are sex workers that were paid 2500 birr ($49) by non-governmental organizations to give false testimony. Another example includes an interview campaign of dehumanizing, victim-blaming, and shaming Tigrayan survivors of CRSV.

Gedion has also attempted to cast a doubt on reports of weaponized rape, even after claiming the government has conducted an investigation, stating that he “will take some of those reports with a pinch of salt” after alleging a campaign of disinformation and exaggeration. Similarly, Daniel Bekele, Chief Commissioner of the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, engaged in character assassination of survivors that testified to their gruesome experience from refugee shelters in Sudan by suggesting they are criminals and not credible. The Tigrayan refugees in Sudan have experienced some of the most gruesome crimes of weaponized rape and have relied on health professionals in these camps for life-saving medical care.

Odious Comparison: Justifying the Crime

In addition, there has been an extensive propaganda push justifying the reported rapes using odious comparisons. Abiy Ahmed was one of the first to use his position of power to use dubious comparisons in an attempt to justify the act. During a parliamentary session, Abiy replied to a question on sexual violence with “The women in Tigray? These women have only been raped by men, whereas our soldiers were humiliated with bayonets.”

Another means of denial has been contending that the victims were non-civilians. One of the examples of this has been the widespread disinformation in an attempt to discredit the testimony by Mona Lisa Abraha, an 18-year-old woman who was raped and shot by Eritrean soldiers, after which her arm was amputated. Officials such as the Head of Public Affairs of the Eritrean Embassy in Scandinavia, Sirak Bahlbi, shared doctored and false images claiming Mona Lisa was a fighter. These images have been debunked after being widely shared.

Odious Comparison: Pre-War Campaign Against SGBV

Most dangerously, high-profile individuals, reporters, and government spokespeople have actively and deliberately spread disinformation about pre-war gender-based violence (GBV) in Tigray to minimize and justify the weaponized CRSV committed by the Ethiopian government and its allies.

This line of argument contends that there was a “culture” of sexual violence in Tigray prior to the war, suggesting that the weaponized rape unleashed on the Tigrayan population is somehow more justifiable and less horrific as a result. The implications of this argument are clear: survivors and advocates should not raise alarm, demand justice, or request support because this is just a “normal” part of the life of Tigrayan women and girls. Sadly this perspective was carried into the report of the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Joint Investigation into atrocities committed in Tigray.

This talking point is not only patently untrue but it also has dangerous implications not only for survivors in Tigray but all people affected by CRSV. First, there is no evidence or data to support the assertion that GBV was more prevalent in Tigray than anywhere else in Ethiopia. While GBV is a widespread problem not only in Ethiopia but across the broader East Africa region, there are no studies that illustrate regional variation within Ethiopia. Second, GBV that occurs during peacetime and weaponized CRSV, deliberately deployed as a tool of ethnic cleansing and genocide, are different both in law and in effect. As noted above, CRSV is considered a crime under International Law, Criminal Law, and Human Rights Law because the intent and impact are qualitatively different from GBV. The former is committed with the intent to brutalize and terrorize a community, often an ethnic or political minority, during the war.

Finally, those who espouse this talking point claim that the presence of grassroots movements against GBV in pre-war Tigray is indicative of a higher prevalence of GBV in that region. This claim is based on the false assumption that the presence of grassroots movements against a particular phenomenon means that the phenomenon is more extreme in that place than elsewhere. In fact, the presence of powerful grassroots movements indicates that there is a community that has the capacity and willingness to identify injustice and take measures to mitigate it. Those grassroots organizations in Tigray, such as Yikono, led by young women who were strong allies were able to identify and demand justice for GBV in their communities indicating their social awareness, determination, and bravery in fighting for justice. Committed male allies supported this movement and the government of Tigray also showed significant interest in addressing this issue. The same advocates who fought against GBV in pre-war Tigray are still engaged in this fight, demanding justice and support for survivors of CRSV in Tigray.

Implications and Future Directions

As such, the talking points utilized by state and state-allied spokespeople that seek to whitewash and deny the CRSV committed during the war on Tigray are based on faulty assumptions and unsupported by evidence. However, the implications of these arguments ought to be taken seriously by those concerned with preventing CRSV in the future. If the claim that the presence of grassroots organizations is indicative of the prevalence of injustice is uncritically accepted, it opens the door for social justice movements to be weaponized against the very communities they work to serve. Feminist advocacy against GBV may be used to justify CRSV, as it has been in Tigray as can any type of advocacy that strives to identify and challenge injustice. Therefore, it is vital to challenge and illustrate the dangerous and malicious intent behind these talking points that strive to weaponize the work of community advocates to further attack their communities.

Any effort to normalize the deliberate and systematic use of sexual violence as a weapon of war by states and armed groups is morally reprehensible. But to use the work of brave and committed women advocates who organized during peacetime to raise awareness about GBV to justify the horrific CRSV committed against women and girls is beyond deplorable. In addition to being morally wrong, this nefarious talking point presents a clear danger to any community-led, grassroots efforts to challenge injustice.

As such, there needs to be a concerted effort by different bodies, including social media platforms, international organizations, human rights bodies, and donor countries. We particularly ask social media platforms to recognize the coordinated denial, downplaying, and gaslighting of survivors and communities traumatized by CRSV as hate speech, and denial of violent crimes, and take appropriate actions as outlined in community guidelines. Similarly, we call on international organizations, human rights bodies, and donor countries to denounce the denial of CRSV and the gaslighting of victim communities. In addition, it is important that media, international organizations, human rights bodies, and donor countries cut ties with local, regional, and international figures and groups that are engaged in denying CRSV and other practices revictimizing survivors and victim communities. Furthermore, the diplomatic community must deploy all means available to assist survivors that are facing physical, psychological, and socio-economic impacts that are long-lasting. There need to be concerted efforts at all levels to stop the continued denial of survivors’ access to care, rehabilitation, support, treatment, protection, and means of expression. This includes the deploying of tools to protect Tigrayans from the redeployment of Eritrean and Ethiopian troops to Tigray.

It is critical for all to center on survivors and victim communities in all of their approaches and outputs.

Saba Mah’derom is a masters student based in the U.S and a board member for Women of Tigray.

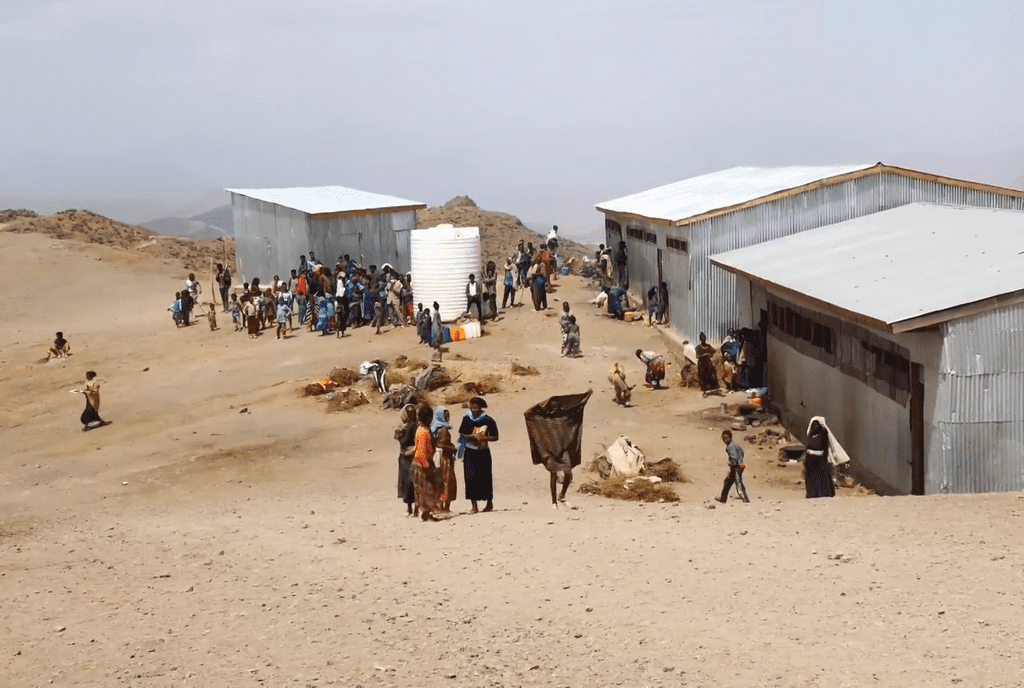

Photo: Clothing, Tigray, Ethiopia, Rod Waddington (CC BY-SA 2.0)