America versus the Houthis in the Red Sea: what the confrontation means for the rest of the world

It’s time to rethink global maritime security. The current system—based on the US Navy—isn’t working and isn’t sustainable.

In its air attacks on Yemen, the US sent both lethal missiles targeted at Ansarallah, known as the Houthis, and messages to the American public, the Middle East, Europe and the global trading system.

The immediate public rationale for the American attacks is that they will degrade the Houthis’ military capabilities so that the Houthis will be unable to attack Israel or ships in the Red Sea or will be decisively deterred from doing so. These goals are unlikely to be achieved.

It’s true that international ships are at risk. According to different metrics, between 12-15 percent of world trade passes through the Red Sea including most container ships sailing between Asia and Europe. The US Navy is the self-appointed guardian of the sea lanes. That’s not sustainable.

US Vice President JD Vance texted in the no-longer-classified Signal group chat, ‘The strongest reason to do this, as POTUS said, is to send a message.’ In fact, the US is sending several different messages.

- For domestic audiences: the Trump team is muscular.

- For the Middle East: Israeli priorities trump everyone else’s concerns.

- For the BRICS: trade corridors are part of the trade war.

- For Europeans: pay up or pay the price.

- To the world trade system: don’t expect to continue relying on the US Navy.

The air strikes have put the question of global maritime security on the table. That’s needed. What’s important is to have the right debate. In the Red Sea, this means addressing not just the safety of ships, but peace and stability on shore as well. It means a multilateral arrangement involving global cooperation. Above all it means thinking of sea lanes protection as a political project for peace.

There’s No Military Solution

If the metric of the air strikes’ success is destruction or deterrence, this would mean that the US has to succeed where seven years of bombardment by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates plus ground attacks failed.

‘Operation Decisive Storm’—the Saudi-led bombing campaign against the Houthis was launched almost exactly ten years ago. Its name stands as a warning against those who seek to repeat the exercise. After seven years of attacks, along with ground offensives by Yemeni armed groups and foreign mercenaries, Saudi Arabia and its key ally, the United Arab Emirates, decided to opt for co-existence.

It’s possible that the US, in concert with Israel, may succeed where the Gulf states failed. Few analysts believe that it will happen.

The Houthis declared that they were standing in solidarity with the Palestinians of Gaza, a stand that was wildly popular across the Arab world. The Saudi leadership cannot wholly ignore public opinion.

The Houthis said they would selectively target ships associated with Israel and its allies and would cease attacks in the case of a ceasefire in Gaza—and have by-and-large conformed to that. But their attacks have not been as discriminate as they claimed. They are a real threat to any ships. They have deterred shipping companies and driven up insurance costs. The attacks are crimes in international law regardless.

Using force to protect ships under attack is perfectly legitimate. But exactly how far the US can lawfully go in using force is unclear.

The Biden Administration launched ‘Operation Prosperity Guardian’ in December 2023 after the first Houthi attacks on shipping. The US then sought a UN Security Council resolution to endorse US strikes on ground targets. While other states supported the US right to protect shipping, many of them didn’t support the stronger measures against ground locations.

Few other countries joined the American-led coalition. Particularly conspicuous by their absence were the major US allies in the region, namely Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

One of the Houthi missiles came within seconds of striking a US warship. If American sailors had been killed and a ship had been damaged, what was billed as a policing action could have sparked something far more dangerous.

The Europeans also had reasons for skepticism. Almost twenty years ago, as piracy in the Gulf of Aden and western Indian Ocean escalated, the European Union launched Operation Atalanta, a multinational coalition for policing the sea lanes. It was remarkably successful in reducing attacks on shipping. Anti-piracy was operationally and politically much less contentious than exchanging fire with the Houthis. But it has important lessons nonetheless.

Like war, security missions are the conduct of politics by other means. Success is defined by political objectives. Key policymakers in the European Union and their counterparts in north-east Africa understood that maritime security required on shore peace. Pirate attacks from the Somali peninsula could be sustainably reduced only with a program to improve governance and livelihoods among coastal communities. In turn, that demanded a strategic approach to peace and security involving the countries of the Arabian peninsula, the Horn of Africa, Egypt, and a range of other states with commercial and security interests.

Resolving the US-Israeli war with the Houthis is much more challenging than suppressing piracy. But it is a political project nonetheless that requires a political strategy.

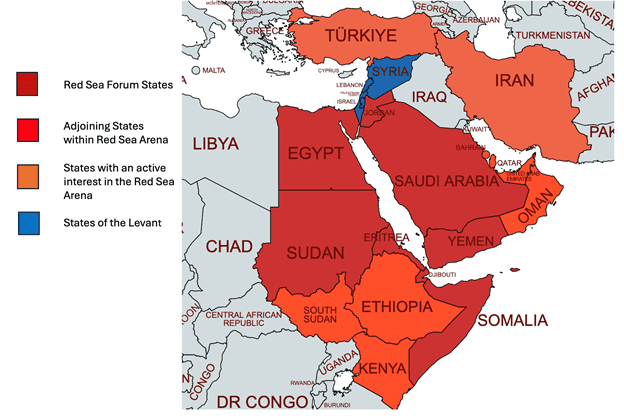

A Political Perspective: The Red Sea Arena

The concept of the ‘Red Sea Arena’ was born out of the experience of the multilateral suppression of piracy and peace and security architecture of the Horn of Africa. It’s an ‘arena’ in two senses.

First, it isn’t a region in the conventional sense of a grouping with shared institutions or norms. An arena is where people go for a contest—a fight or a performance. Like a boxing ring it may be a fight with a real risk of injury. It may be a ‘sell game’ in which a gambling cartel has bribed the contestants, or the referee, and fixed the outcome. Like the World Wrestling Entertainment, what looks like a fight may be a performance staged for profitable entertainment.

Second, it has concentric circles of states with varying levels and kinds of interests.

The arena’s inner tier is the countries of the Red Sea Forum, which is a grouping convened by Saudi Arabia that includes all the littoral states of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden except Israel, i.e. Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. Egypt has a special place because the Suez Canal brings in major revenues—$9.4 billion in 2022/23. Since the Houthi attacks started, revenue is down 60 percent.

The arena’s middle tier is neighboring countries with a commercial or security interest in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. On the African side this includes Ethiopia, Kenya and South Sudan. Ethiopia is particularly important because it is the world’s most populous landlocked country and its leadership is actively seeking a port. On the Arabian Peninsula side this includes Qatar, Oman and the United Arab Emirates, plus Israel, and other regional powers that have active engagement (Iran, Turkey) and, more distantly, Lebanon, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Syria. The UAE is a particularly significant actor because it is assertively pursuing influence across the southern Red Sea Arena and acquiring and building naval bases. For Israel, the Red Sea is its back door.

In 2024 and 2025, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Turkey and the UAE joined the BRICS while Saudi Arabia is equivocating on whether to join.

The Red Sea Arena framework was used by the U.S. Institute of Peace, which issued a bipartisan report on the topic in 2016. (Since USIP was shuttered by the Trump Administration and its website taken down, the report is only available on the Wayback Machine.) A follow up report was due to be issued this month but is fate is uncertain. Europeans have also adopted this lens.

The key point shared across all these analyses is that a political resolution of onshore conflicts is necessary to increase the safety of shipping. This was true when the conflicts in question were the civil wars in Somalia and Yemen. The conflict between the Houthi-Hamas axis and the Israel-US alliance has implications of a different order of magnitude but it is also a political conflict.

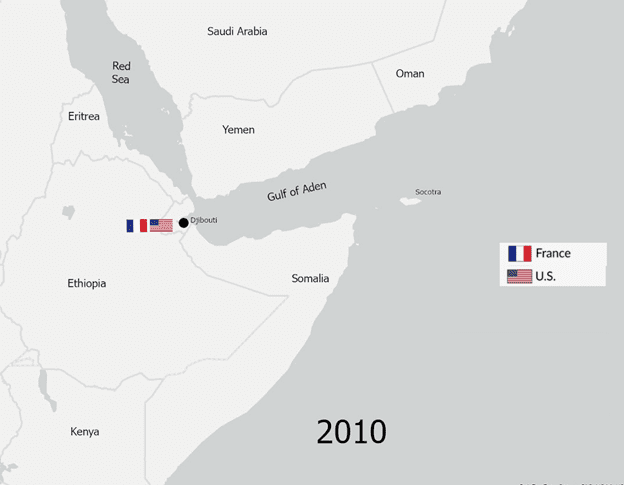

But the logic is in the other direction. These were the foreign-owned ports and naval facilities in the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in 2010.

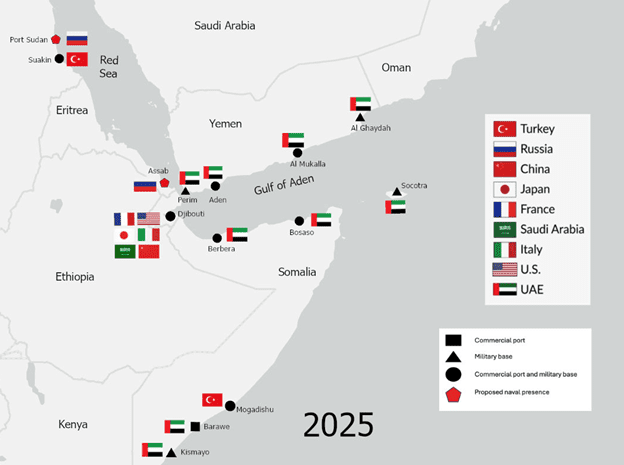

This is the situation today: a scramble for military and commercial real estate. This is where a ‘trade war’ can become something more than a metaphor.

The outer tier in the Arena is the global actors that have trade and security interests, including China, the European Union, India, Russia, the UK and the US.

For China, the Red Sea is the ‘buckle’ on its maritime belt, the major route for its commercial traffic with Europe. It has a naval facility in Djibouti—its first such base in what it calls the ‘far oceans.’ Despite those major commercial interests, China has stood aloof from the conflict with the Houthis. The Houthis say they won’t attack Chinese ships.

Russia is seeking Red Sea naval bases. Europe is concerned because so much of its trade passes this way.

The $40bn Question: Global Sea Lanes Protection

The US argues that that China is having it both ways—it negotiates with the Houthis for exemption from attacks while benefiting from any military successes achieved by the Americans. China spends next-to-zero on sea lanes protection while in the years to 2023 the US spent $40 billion on this globally—not counting the additional expenses of its operations in the Red Sea.

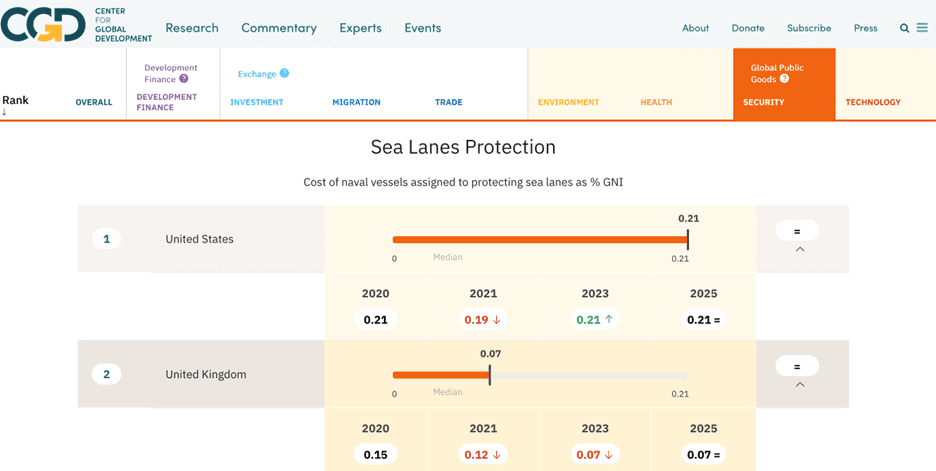

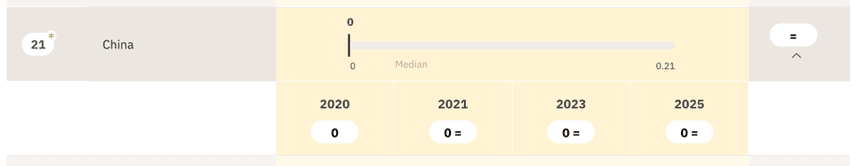

According to the Center for Global Development data,

The US ranks 1st on sea lanes protection by a significant margin, contributing an equivalent of 0.2 percent of its GNI in naval vessels protecting international waters, as compared to a CDI average of 0.015 percent, and with the next-best country, the UK, providing less than half as much at 0.07 percent.

China is at zero on this indicator.

Globally, this is as big a deal as the question of NATO.

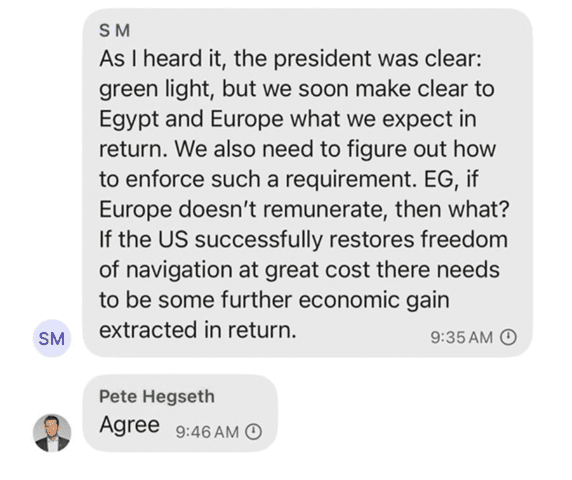

Vice President Vance referred to this in the Signal group chat. But he texted that only 3% of US trade passes through the Suez Canal, while 40% of European trade does, so that he saw the action as ‘bailing Europe out again.’ Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth texted, ‘I fully share your loathing of European free-loading. It’s PATHETIC.’

And another question arose later in the chat, from ‘SM’:

Maritime security should be on the global agenda. Under successive American administrations, this has been framed as a question of the number, location and posture of warships. The Trump Administration has simply made this overt and added the price tag, opening a bargaining session over who picks up the tab.

The transactional method is not going to provide the needed security. It will accelerate the scramble for strategic real estate, which, in several arenas around the world, risks conflict. But more fundamentally, it presupposes the wrong question. Maritime security is a political issue first and a shipping safety issue second. It cannot and should not be done by the US Navy acting almost alone. That’s the lesson of the Red Sea Arena.

In all the noise around the air strikes and the Signal group chat, President Trump’s action should do one important thing: opened a debate on these questions.