For the first time in history, starvation is at the center of international law. And judges at the International Court of Justice face a challenge for which they are perhaps under-prepared.

The core question is this: given that the judges have been presented with evidence that Israel has brought the population of Gaza to the brink of mass starvation, what urgent remedy should Israel be instructed to provide?

The issues are legally and factually complex but the core issue is very simple: it’s wrong for Israel to starve people and it has stop at once, and do its utmost to save lives.

In a simplified form, the logic of South Africa’s application to the Court is that there is a plausible case that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinians of Gaza, based on (a) public statements by the most senior government officials that, prima facie, display genocidal intent and (b) evidence that Israel is committing acts prohibited under the Genocide Convention, causing immense human suffering and death.

As observers including Alon Pinkas in Haaretz have pointed out, the path to South Africa making a credible case at the ICJ was laid by public incitements made by senior Israeli leaders, including Benjamin Netanyahu, in his infamous Amalek statements. It was these statements that opened the door to the ICJ hearing the case under the Genocide Convention.

International mechanisms for adjudicating whether Israel is committing war crimes or causing famine either do not exist, do not possess the same weight, or (in the case of the ICC) would prosecute individuals long after the fact. But once the door to the ICJ has been opened, issues that would not otherwise have come before an international court, at least not in an expedited manner, press their way in. Among them is starvation.

Much of the weight of the South African case is carried by Article II(c) of the Genocide Convention:

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or part.

For the purposes of this blog, I will assume that the right protected here is essentially the same as that protected by the war crime of starvation, as defined in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 8(2)(b)(xxv):

Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare by depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival [OIS], including wilfully impeding relief supplies as provided for under the Geneva Conventions.

The war crime of starvation does not have to cause mass death to qualify as a crime. In the case of Gaza, it is coming close. Once the threshold of mass mortality from hunger and related causes is crossed, the relevant lenses for assessing culpability and, especially, considering remedies are broadened. It’s simply an empirical fact that a widespread acute humanitarian emergency demands bigger and more urgent measures than a less severe crisis.

According to the framing of ‘famine crimes’ developed by David Marcus, we can distinguish between a ‘first-degree’ famine crime, when famine is inflicted at scale with the intent of genocide or extermination, and a ‘second-degree’ famine crime, which is the reckless continuation of a policy of starvation without such intention, but nonetheless continued even in the knowledge that famine is the likely result.

The ‘famine crimes’ framing is relevant because the ICJ cannot now ignore the imminence of mass death from hunger, disease and exposure.

It is important to underline that, just as the judges do not need to make a determination on genocide in order to instruct provisional measures, neither do they need to decide that a threshold of ‘famine’, or any other metric for humanitarian crisis, has been crossed. But those measures need to be sufficient to address the humanitarian emergency as it actually is.

Once the ICJ has accepted that the rights threatened in the Genocide Convention are threatened, its judges cannot in good conscience issue a ruling that might in any way allow Israel to commit war crimes or pursue faminogenic actions, even if those crimes fall short of genocide.

South Africa has demanded nine provisional measures in paragraph 144 of its Application.

The first is an immediate suspension of hostilities by Israel. It is reasonable to expect that the Court will not grant this because, as the Israeli counsel has argued, it would be imposing a cessation of military activities on one party to a conflict (Israel), and not on the other (Hamas).

Wars can be fought without genocidal intent and without causing such high levels of destruction of OIS that humanitarian emergency and famine ensue. In short, military action need not be faminogenic. The Court may consider ordering Israel to desist from destroying OIS and other faminogenic actions in its ongoing military actions.

Provisional measures 4 and 5 in South Africa’s application would impose restrictions on the military activities that Israel could undertake. Measure 4 restates the prohibited acts in the Genocide Convention, replicating its Articles II(a)-(d). Measure 5 elaborates on Article II(c), demanding:

The State of Israel shall, pursuant to point (4)(c) above, in relation to Palestinians, desist from, and take all measures within its power including the rescinding of relevant orders, of restrictions and/or of prohibitions to prevent:

- the expulsion and forced displacement from their homes;

- the deprivation of:

(i) access to adequate food and water;

(ii) access to humanitarian assistance, including access to adequate fuel, shelter, clothes, hygiene and sanitation;

(iii) medical supplies and assistance; and

- the destruction of Palestinian life in Gaza.

This is where it gets tricky. The rationale for spelling out these steps in detail is, presumably, to end the humanitarian emergency in Gaza in an expedited way and to save lives, especially the lives of children who are most at risk.

The difficulty is this. If the acts in question were shooting or bombing, then ceasing those acts would immediately end death and destruction. The case of mass starvation is different. Humanitarian emergency is like a heavy, fast-moving freight train. The driver can apply the brakes with full force but it will still take many miles for the train to come to a halt.

The actions spelled out in provisional measure 5 would significantly mitigate but not, in themselves, end loss of life from hunger, disease and exposure.

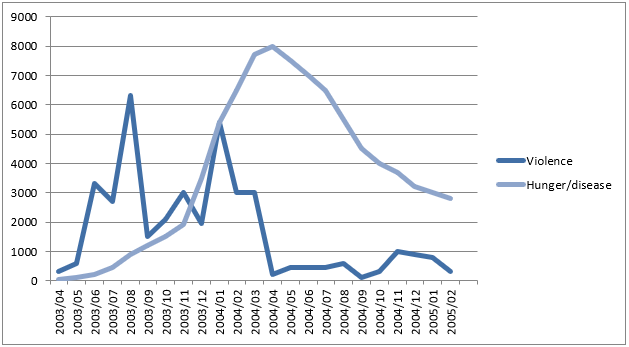

Typically in a humanitarian emergency or famine caused by war, deaths from hunger and disease continue to rise, or are slow to fall, even after a ceasefire. In my testimony to the ICC in the case of Ali Kushayb, standing trial for crimes committed in Darfur, I submitted the following graph, which shows deaths from violence (spiky line) and deaths from hunger and disease (smoother line):

The impact of the Humanitarian Ceasefire of April 2004 can clearly be seen: violent deaths sharply declined and deaths from hunger and disease peaked and began a slow decline. Nonetheless, more civilians perished from hunger and disease after the ceasefire and the associated scale-up of humanitarian aid, than beforehand.

Returning to the case of Gaza, even if Israel were immediately to cease the destruction of OIS and allow humanitarian assistance to flow unhindered, the death toll through hunger and disease would continue to mount for some time, possibly passing the threshold of famine even if the faminogenic actions had themselves ceased.

In short, provisional measures 4 and 5 might not be sufficient to prevent the people of Gaza dying from hunger and disease en masse. Even a total suspension of military action by Israel might not be sufficient.

Gaza needs a truly massive, immediate and unhindered full spectrum emergency relief effort.

The major part of the responsibility for providing this falls upon Israel, as the occupying power and the party responsible for the faminogenic acts. Israeli leaders seem unbothered with hunger. The Court can change that.

The fact that the Court cannot instruct Hamas to take actions such as ending its practice of stealing essential relief items, and the fact that Hamas may take advantage of Israel desisting from destroying OIS and imposing a siege, is simply a price that Israel has to bear. Restrictions on the conduct war for humanitarian purposes are the cost of humanity.

What the ICJ can do is ultimately quite simple: instruct Israel, unconditionally, to do everything in its power to desist from actions that are creating starvation and instead provide and facilitate a full-spectrum of humanitarian assistance without any hindrance or delay.