It’s often been said that democracy and a free press are the best famine prevention measures. The claim was famously put forward by Amartya Sen and has been challenged and refined by Dani Banik, Olivier Rubin and a number of others, focusing especially on India’s post-independence record.

What does the World Peace Foundation historic famine dataset show? In this blog post I present three graphs derived from our data.

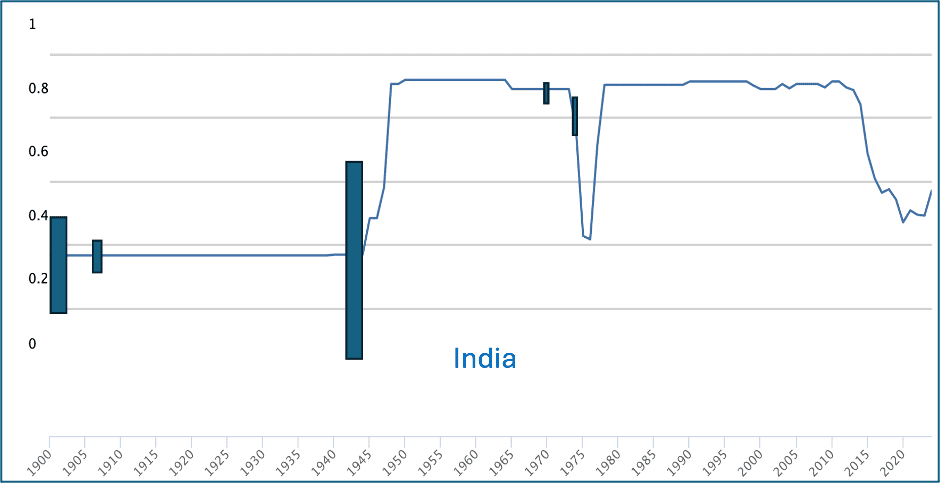

The first graph shows the rating of India on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset freedom of expression score. The score ranges from zero to 1. The data cover 1900 to the current day. I have put rectangles representing famines in India on the graph, their size proportional to the numbers of people who perished.

Figure 1: Freedom of Expression (V-Dem) and famines in India

There are five famines: 1899-1901, which killed a million people in the Central Provinces and Bombay; 1906, a smaller famine that covered much of the same area; the 1943 Bengal famine which killed 3 million; the 1966-67 Bihar famine and the 1973 Maharashtra famine. (There were also many famines in the previous few decades.)

It’s clear that after independence in 1947, freedom of expression was much improved, and famines declined. How to explain the clear exception, whic is the Bihar famine? This case was explored by several scholars, including Thomas Plümper and Eric Neumayer, who argued that governmental inaction in response to a well-publicized problem was explicable because of the small size of the affected population and its low political weight. The Maharashtra famine struck just as India was descending into a short-lived period of emergency.

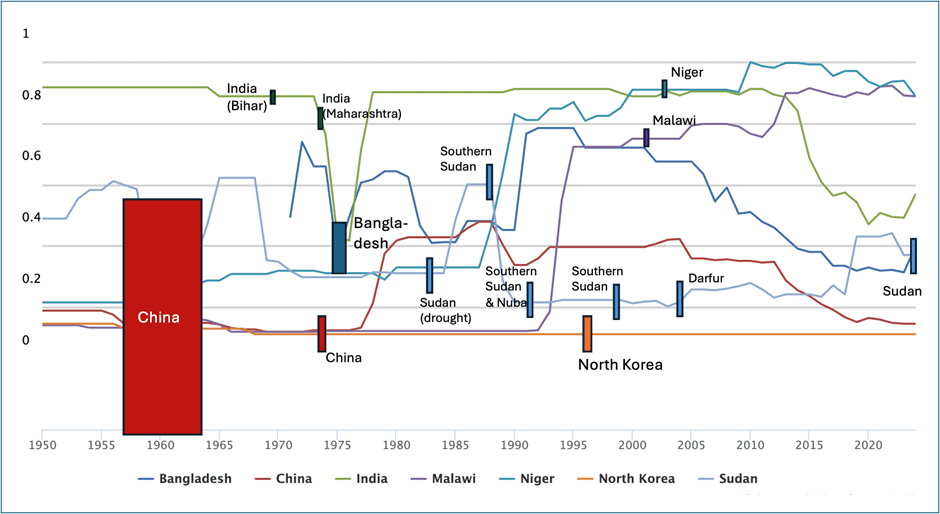

Now let’s bring several other countries into the picture: Bangladesh, China, North Korea, Malawi, Niger, and Sudan. These are the countries studied by Rubin and other scholars who have worked on this topic.

Figure 2: Freedom of Expression (V-Dem) and famines in selected countries

For the famines with the largest mortality, the association remains pretty clear. It’s most striking for the 1958-62 ‘Great Leap Forward’ famine in China, the North Korean famines, the Bangladesh famine and all-but one of the Sudanese famines.

How to explain the outliers. These are the famines in Malawi and Niger and the southern Sudan famine of 1988, which occurred during the period of parliamentary government when there was relative freedom of expression?

Three possible factors jump out.

One: excepting southern Sudan, the cases at freedom of expression scores of 0.5 or above are all smaller famines, that didn’t hit the threshold of 100,000 dead. For whatever reason, they’re less lethal.

Two: governments simply didn’t have the capacity to act. This is arguably the case for Malawi. It wasn’t a collapsed state, but as Stephen Devereux and Zoltan Tiba have argued, it had almost zero room for maneuver in its economic policies.

Three: the famines struck minority populations that counted for less politically. This has been argued for the Indian cases and for Niger.

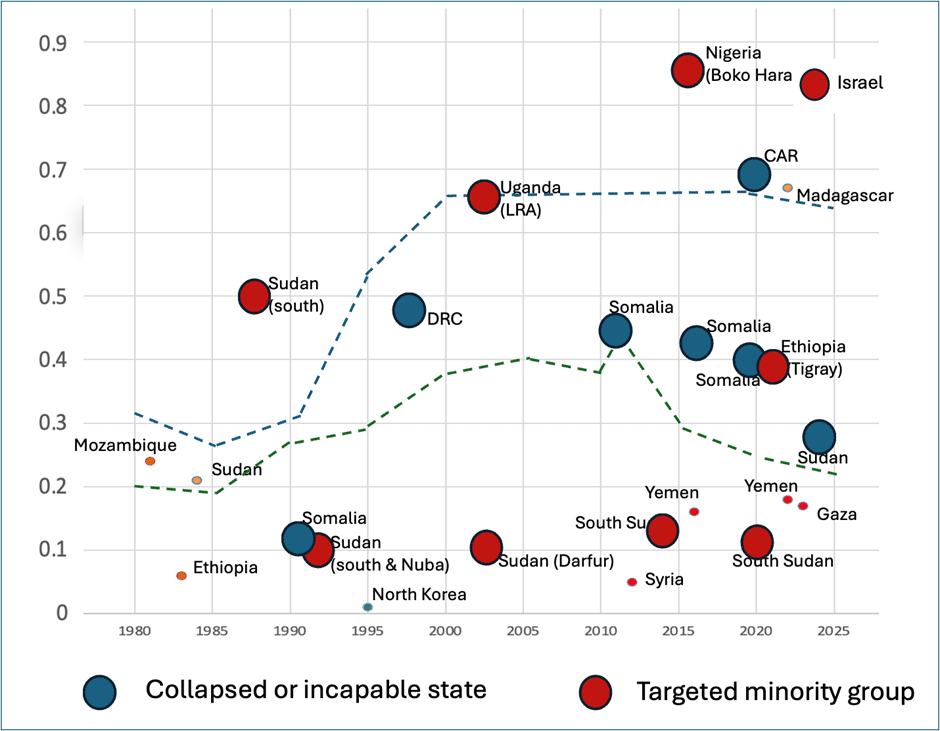

We can amplify this by putting all of the cases in the WPF historic famine dataset, and all those reviewed by the Famine Review Committee of the Integrated food Security Phase Classification, on a chart with the freedom of expression scale.

Figure 3: Freedom of Expression (V-Dem) and cases in the WPF famines dataset

The dotted lines show the average V-Dem scores for sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa regions respectively (the SSA is the higher line). It’s that very few famines strike in countries ranked above-average. And almost all that do are either collapsed or incapable states (e.g. CAR, DRC or Somalia) or the famine is striking a targeted minority (southern Sudan, northern Uganda, north-eastern Nigeria, Tigray in Ethiopia, or Israel’s targeting of Gaza).

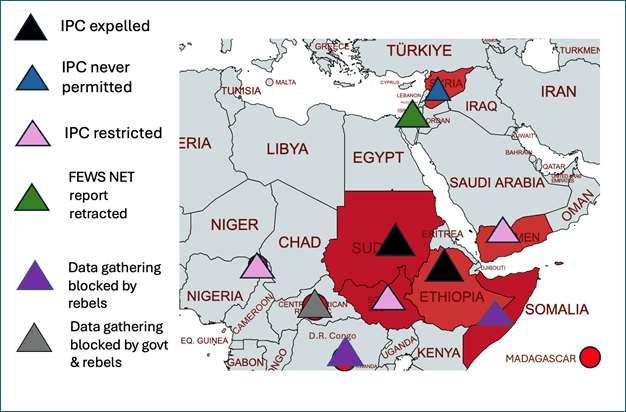

Censorship extends to the suppression of humanitarian data too. Almost everywhere where famine early warning and response systems try to operate, the authorities try to stop them, or manipulate them. Look at this map, of places where the Famine Review Committee has conducted famine reviews plus countries where there is good evidence for excess deaths exceeding 100,000 (CAR, DRC, Syria).

Figure 4: Countries where humanitarian data gathering is restricted.

The outlier on this map—and in the previous figure—is Madagascar. It’s an anomaly because it is solely a crisis caused by climatic stress (prolonged drought) and also because aggregate mortality is much smaller than all other cases.

Conclusion: hypothesis confirmed. Most famines—and especially most big famines—strike in the dark.