A letter from a young professional living in Tigrai

I am writing to share my story with the world as the world seems to be acclimatized to live with our suffering in Tigrai. From time to time I hear the international media struggling to put a positive light on the regime in Addis Ababa following the release of few thousand tons of wheat to Tigrai. But our suffering is not to be ended by allowing these deliveries of wheat and humanitarian aid to trickle through the encirclement. We Tigraians are as much human beings as the rest of the world and we deserve a dignified life.

I know that the world fully knows the horrors that are taking place in Tigrai and its inactions are not because it doesn’t know what is happening. Nevertheless, there is little that I can do except to continue telling my story and to continuously appeal to humanity no matter how repeatedly the world might have heard these kind of stories. Here under is my story.

I am living in Mekelle surviving the genocidal war—though it is debatable on whether it counts survival or a slow death. My name is Birhan which means light/world. My parents told me that they gave me the name Birhan because I was a light of hope for them. And a lot of my friends use to tell me that my name suits my personality. They knew me of being understanding, caring, and excessively sociable, which is not the case anymore. It all feels now dark and uncertain and couldn’t find my older self in the current environment. I am an electrical engineer by training and lecturer at Mekelle University. But that was 18 months ago. Since the start of the war in November 2020, the university has been closed and I don’t have a job and a salary like everyone else in Tigrai.

The moment the war broke and Mekelle was under the control of the Ethiopian force, I had the chance of getting out of Tigrai to Addis Ababa. I even had a chance to go abroad for better opportunities. I had two scholarships that I worked hard for and that were finalized. All I had to do was leave. However, I never felt like running away when the people of Tigrai began to face crimes more heinous they have even seen in their history. My fellow Tigraian sisters were being raped and my brothers being killed at the time I was making a decision whether or not to leave the country. I chose to stay with my people as I felt running away for my individual safety was selfish. I don’t know if that was the right choice or not, but I deeply believed it was the right decision at the time.

It had become the task of each and every Tigraian to think of what to do to avert the danger of extinction.

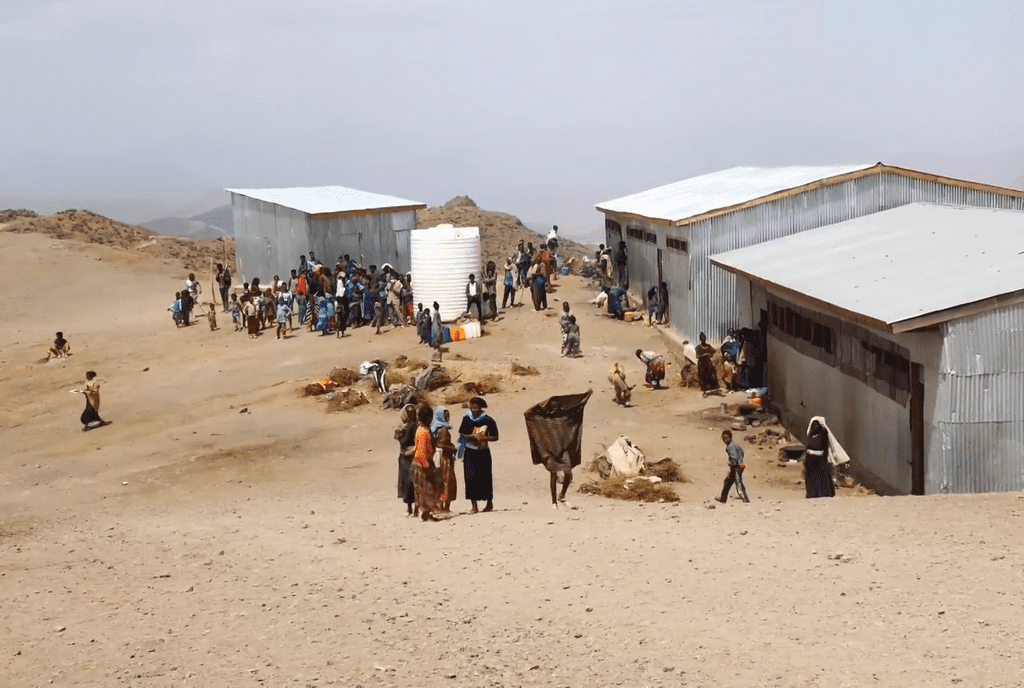

It had become the task of each and every Tigraian to think of what to do to avert the danger of extinction. It was at this time I decided to return to Tigrai and help those in need as my way of contributing to the survival of my people. The moment I returned I began witnessing horrible and disturbing things happening to my people and decided to do whatever I can to avert those things. I started doing voluntary jobs. Few months into the war Mekelle was filled by tens of thousands of internally displaced persons, from all over Tigrai. Like so many residents of Mekelle, I started spending all my time helping: raising food and non-food items and money to help feed them; facilitating the work of NGOs working to help the IDPs, and helping them in organizing themselves in those makeshift camps they were staying. This was fulfilling for me at the time. With the war continuing though, resources began to deplete and delivering those services continued becoming more and more difficult.

About eight months into the war, the Tigraian forces took over different cities. When the Tigraian forces took over the Mekelle, everything got shut down again. Banks got closed, telecommunication and all land and air transport to and from Tigrai was closed, Tigrai was cut out of the national electric grid, and fell under a complete siege by hostile forces. Life got even more difficult in Tigrai. Personally life became more difficult with no access to the little money I had in the bank and everyone’s life became tougher and harder.

Many of my friends volunteered for military training and joined the TDF to try to bring the war to a rapid end. At the resumption of free movement within most of Tigrai, the extent of the heinous crimes committed by the aggressors began to be known and I decided to document the stories of the victims of sexual violence. When talking to the victims, the hardest part was not being able to feed them. They start crying when talking to me, their kids also cry. After all their abuse and rape, all the psychological trauma, they had to deal with hunger as well. I couldn’t do anything to help them but cry with them. Once I finished documenting, the gruesome stories I heard haunted me and forced me to pass sleepless nights.

Few weeks after I finished with the documentation, I found one of the victims I interviewed passed out on the street. I tried to organize some assistance for her during that time. She is one of the many women infected with HIV during this war. The moment I got her, she seemed intoxicated of alcohol and I took her to a hospital with the help of friends. In the morning she was fully conscious and told me that she had no option but to sell her body for survival and got used to alcohol as a way of escaping the shame she felt. This life has become the fate of some Tigraian victims of sexual violence. There was literally nothing I could to do to her and cursed the world for not doing anything substantial to stop the war and save these women from the downward spiral of life they in which are caught.

I have friends who try to escape by drinking alcohol. Many of you might ask where they get the money to buy alcohol, but you would do anything to get it to escape the daily hardship. I tried it as well but my inside persona fought it back. Whatever you do, there is nothing that helps you escape for longer than a couple of hours. When I ran into some of my former colleagues, they tell me that they appreciate my condition as I am keeping myself busy in some meaningful task of documenting the stories of atrocities. I feel that they don’t understand how deeply painful it is to hear the stories of atrocities and capture them accurately but I also think maybe they appreciate my condition because they are hurting more.

Why do we deserve this? We have lost all that we have worked for our lives for and we have been stripped of all our human rights. How did we get to a point where we can’t even see rebuilding our lives back? If I get through and survive this I am doubtful on whether I can be the same person after all these dreadful experiences.

I’m one of the few people who is fortunate enough to have at least one meal a day for now. One of the few who are not starving on a daily basis. For me to do anything else besides eating for survival is luxury. For my neighbors one meal a day is a luxury. Taking a shared taxi is a luxury. I met a former colleague of mine who has a PhD the other day. She was telling me how hard the situation has been. She was in a taxi when someone she saw someone knows who was begging, and she only had just enough for the taxi ride, but she was ashamed that he was begging for food and she wasn’t able to help. She had to hide so he wouldn’t see her. Not being able to afford things is a pain but not being able to help others is even more excruciating.

I have been lucky enough to communicate with my family outside Tigrai. All communication is closed but if you find someone that has access to internet, which is rare, you can record a voice note to send to your family and they will send a message back through that person, which then I tell my family. This opportunity for communication is very rare. And waiting a message back can take days, so the message you get can be ten days old and you don’t know what can happen with in those ten days. It is a very emotional process. But still I feel like I am luckier than the millions who haven’t heard from their families for over a year. Life goes on. It is like being a prisoner with no rights.

I have a lot family and friends, who are confused about what will come next. They are not sure that they will survive this crisis and not sure how to start life if and when they survive it. The impacts of the trauma are deep and will to continue for years even after the end of the siege.

Recently I am having problems remembering things. People’s names and other things are becoming hard to remember. I was sharp minded, and I had an impeccable memory, but I wouldn’t even remember what I ate yesterday. My brain feels weak. I can’t plan anything because I would forget it anyway. This is happening to most of us. I was talking to an older woman walking to the city center, when suddenly she realized that she forgot to lock her house. She said to me “this war has left us empty, to where we can’t even think straight”. I doubt that we will get back to our old selves after this. I doubt I will be the Birhan I used to be, the sharp minded university lecturer. If I am lucky enough to survive, I just hope I will be able to get back to some kind of normalcy.

Death has become part of our daily life. Most of us has become desensitized to it. I hear of people dying from the smallest things. But no one can’t do anything about it, so I just accept it. I feel like I’m waiting for my turn. Everyday a family member, a neighbor or someone you know dies. They die from hunger, curable disease, stress or something that on this century shouldn’t kill. A woman in our neighborhood died from a dog bite.

When I run into the sexual abused victims, I interviewed for my book, and I can’t help them it kills me inside. This makes me think of the doctors in Tigrai who are trying to treat thousands for various health problems but fail to cure them simply because there is no medicine. They are being broken by every death from curable diseases they witness. All this is in the capital city, and what’s happening in the smaller cities, and urban areas is much worst. There is no communication or transportation so the tragedy is much worse.

When

I go to church and see mothers begging God and praying, it breaks my heart.

What keeps me alive and moving is the determination of the people to survive

this crisis. There is shortage of everything needed for life and yet the people

persevere with the little things they have. They all believe in the type of

resistance they have against the injustices inflicted on them and believe that

they will finally prevail. Their deep culture of sharing and helping each other

and their God-fearing manner are all seemingly little things but they feed my

morale for survival. I am sure the time will come when world becomes ashamed of

its silence up and reckons with its moral failures.

Birhan is a lecturer at Mekelle Institute of Technology of Mekelle University. Recently she has co-authored the stories of atrocities of Tigraian women focusing on gender based violence in her local language Tigrigna and is working to translate it into English. The Tigrigna version of the book is soon to be published and is looking for a publishing partner for the English version of the book. She can be reached at birhansk70@gmail.com