The civil war in Ethiopia is reaching a point at which the government of Ethiopia is actively seeking the intervention of UN Security Council members. It is time for the UNSC to be involved and adopt a resolution. But if it goes about this the wrong way, a UNSC resolution could be an obstacle to peace, not an instrument for it.

There is no place in the world where the global asymmetry of power plays out vividly as much as the UNSC. No matter whether the rest of the members of the Security Council agree, there can be no resolution so far as any one of the permanent five members of the UNSC object to it. The UNSC has held eleven sessions on Tigrai but ended without even a single official statement. Russia and China—shielding themselves by the position of the three African members of the Council—defined the Tigrai problem as an Ethiopian internal problem and obstructed any process that might have led to even a press statement of concern, leaving the UNSC at its default position of leaving the matter to the government of Ethiopia.

Indeed, any internal Ethiopian issue should have been left to the government of Ethiopia had the government perceived sovereignty as a responsibility and acted to protect the wellbeing and security of its citizens. The very reason the Tigrai problem became an issue to the UNSC was the fact that the Ethiopian government not only failed to protect people but declared a genocidal war on the people of Tigrai. One can see that the decisions of council members depended on political expediency and their principles rather than concern for sovereignty.

Despite this structural bottleneck the UNSC frequently comes out with resolutions on issues of collective security. Some of the decisions of the Security Council, however well intended they were become a millstone around the UN’s neck because they are far from the reality on the ground. UNSC resolution 2216 on Yemen is the best example for such a phenomenon.

The balance of power on the war on Tigrai has changed in favor of the Tigraian Defense Forces. This new development might likely create a renewed appetite for the UNSC towards adopting a resolution. In such a case the council should take enough lessons from its previous mistakes and particularly from its resolution 2216 on Yemen and its consequences.

The Yemen Crisis

Ali Abdallah Salah, former president of Yemen, accepted to leave office for an interim government in exchange for his immunity in February 2012. Yemen during the two years of interim administration was led by Abd Rabbu Mensour Hadi, a man who served Yemen as vice president during the rule of Ali Abdallah Salah. The key mandate for the interim period was preparing Yemen for democratic elections. However, the administration sidelined its original mandate and drifted. Immediate to his ascent to power, Hadi steamrolled the country into membership of the World Trade Organization (WTO) that required various kinds of economic austerity and liberalization measures. It also introduced a new structure of the state. However both measures were considered by many Yemenis as a blatant effort to benefit foreign interests and subdue the rebellious populations through poverty and administrative obscurity. As a result, Yemenis continued to resist the decisions and actions of the interim government in various forms.

At the height of public protest, the interim government of Yemen unilaterally extended the life time of the interim period, a move that was legitimized by the US and the GCC, the lead powers in engineering and legitimizing the interim period. This move intensified the resistance and the Ansar Allah (‘Partisans of God,’ and colloquially called as the Houthi movement) armed movement controlled most of Northern Yemen and Sanaa, the capital in August 2014.

The civil war in Yemen had escalated at the time the UNSC convened and adopted Resolution 2216.

Key problematics of resolution 2216

Despite the good intention of the decision, some articles of the resolution ended up being a millstone around the UN’s neck. The key limitations of the resolution are: its complete and unconditional legitimization to the interim government of Mansour Hadi; its call for the complete and unconditional disarmament of the Houthis; and its demand to the withdrawal of the Houthi forces to its pre-2014 positions.

- The complete and unconditional

legitimization of Hadi’s government

Resolution 2216 in its preamble reaffirms the UNSC’s support for the legitimacy of the President of Yemen, Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi, and calls all parties and Member States to refrain from taking any actions that undermine the unity, sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Yemen, and the legitimacy of the President of Yemen. Strengthening this proposition, paragraph 1((d) of the resolution demands the Houthis to cease all actions that are exclusively within the authority of the legitimate Government of Yemen.

Such a complete and absolute legitimization narrowed the engagement of the UN Special Envoy (UNSE) to the recognized ‘legitimate’ government. Soon after resolution 2216, the Houthis expanded their operations and controlled most of Yemen initially shrinking the control of the government to the port city of Aden and later lost control of that area to a new anti-Houthi force (Islah group) with more local power and ended to being a government in exile. Both the Houthis and Islah in their respective areas of control assumed the role of a government.

Article 7 of the resolution urges all Yemeni parties to respond positively to the request of the President of Yemen to attend a conference in Riyadh. It looks like that the Council assumed the legitimacy of the government is accepted by all parties. However, the legitimacy of the government to the Houthis was dead. They considered that they had no obligation to agree the call of the president for national dialogue. The UNSE cannot engage the new force on the ground unless resolution 2216 is revised. In sum the resolution with good intentions ended being an impediment in any effort towards achieving the original intention of ending the conflict in Yemen.

- The call for the Houthis to end the

use of violence and fully disarm

Paragraph 1(a) of the resolution demands the Houthis to end the use of violence. Paragraph 1(c) of the resolution also demands the Houthis relinquish all additional arms seized from military and security institutions, including missile systems. Furthermore, 1(e) of the resolution demands the Houthis to refrain from any provocation or threats to neighboring states, including through acquiring surface to surface missiles and stockpiling of weapons in any bordering territory of a neighboring state.

The Houthi’s used violence as a means of their struggle to achieve certain political objectives. Unless forced, they can only relinquish the use of violence once they believed their political objectives are met and/or they are convinced that their political objectives can be met through peaceful negotiations. Calling for their complete and unconditional disarmament was therefore unrealistic. The resolution’s call for the Houthi’s not to plan any missile attacks without providing them any security guarantees for attacks from neighboring states was also unrealistic. Ansar Allah in response repeatedly offered to trade a halt in all ballistic missile attacks for cessation of all airstrikes which was rejected by the government of Yemen reasoning that the deal is not balanced.

Issues of disarmament and arms control required care and detailed planning. A more focused and gradual approach would have made sense. For example, one along the preposition of the Houthis, could look into trading missile attacks and air strikes to selected areas as a starter for the process. The exchange could involve a package of areas to be protected in the first stage. Such a deal could be done to incrementally expand its coverage until all of Yemen is free of air strikes and missile/drone launches.

- The demand for the Houthis withdraw

to their pre-2014 positions.

The resolution in Paragraph 1(b) calls the Houthis to withdraw to their pre-2014 positions and demanded them to withdraw from Sana’s and other provinces that were already under their control. During this time the military escalation by the Houthis had expanded to many parts of Yemen including to the Governorates of Ta’iz, Marib, AlJauf, Albayda, and were advancing towards Aden. During time the Houthis had already seized huge cache of arms including missile systems, from Yemen’s military and security institutions.

Why should then the Houthis consider their return to their pre-2014 positions? In exchange to what? They instead demanded a complete end to the Saudi blockade (including the full reopening of all international access routes, whether Hodeida port or Sanaa airport), and an end to what they term the Saudi led “aggression” before they would even consider a ceasefire.

In sum, as far as UN resolution 2216 remains in force, the ToR of any UNSE prohibits him from engaging effectively with both the Houthis and other forces on the ground–namely more representative anti-Houthi forces with more local power than the Hadi government. The special envoy cannot think of creative ways of silencing the guns by negotiating new ways of managing and controlling arms in Yemen. He cannot think of looking into alternative and realistic ways of redeployment of forces as far as the previous decision demanding the Houthis return to their pre-2014 positions is not revoked. Simply put, a resolution the UNSC adopted to address the Yemeni crisis ended up constraining its efforts to bring peace to Yemen. The UNSC should learn enough in dealing with the current war in Ethiopia.

The war in Tigrai

The original cause of the war is rooted in the intention of the Federal Government to tear up the Federal Constitution and replace it with a unitary imperial-like regime run from the center. To this original cause was added a second factor that has become a question of survival for the people of Tigrai: Addis Ababa and its allies violated the laws of war, declared and implemented genocide against the people of Tigrai.

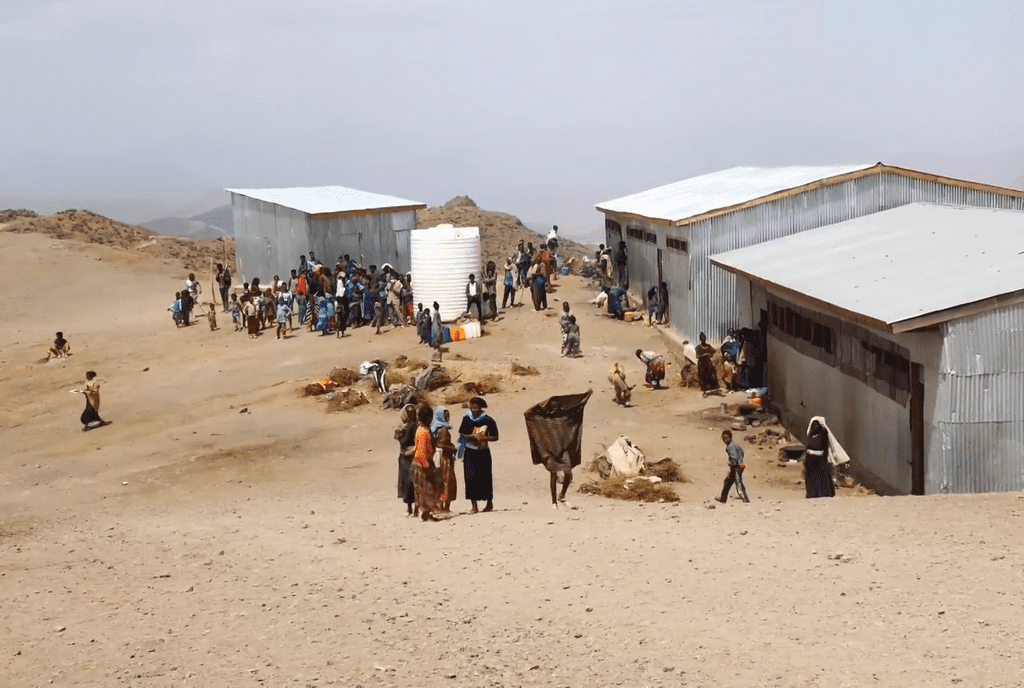

The war in Tigrai is now at its climax where the forces of the Federal Government and its allies are militarily pushed out most of Tigrai and the operations of the Tigrai Defense Force (TDF) has expanded into the Amhara and the Afar regions. Whatever happens next, the TDF has shown that the Tigraian people are undefeated and the strategy of Addis Ababa and Asmara for complete military triumph cannot prevail. Ethiopia now stands on the brink of escalating civil war and state failure. This is the moment to prepare for concerted international action to prevent further drift and complete collapse for this nation of more than 110 million people.

The government of Tigrai insists that it is not seeking outright military victory but rather a political settlement that secures its fundamental interests. It will continue to press its military advantage until the Federal Government in Addis Ababa is ready to negotiate.

In these circumstances, Addis Ababa is lobbying the African Union and the UNSC to take a position that would protect it politically, and thereby complicate the search for a negotiated solution.

The UNSC must take care of not making Yemen like mistakes in its deliberations and decisions. Some of the key issues that need to be handled with care are: All issues related with ‘legitimization’ of either or all the belligerents; issues related with redeployment of forces; and, issues related with disarmament and arms control.

- Correctly name

the parties to the conflict

It is standard practice, common courtesy and a requirement for any negotiations that the parties are named correctly.

It is therefore crucially important that the UNSC should be careful to name each of the parties in the way they call themselves. The Government of the National Regional State of Tigrai is at the center of combating the genocidal war on Tigrai. We can shorten this to ‘Government of Tigrai.’ The TDF is spearheading the resistance war under the auspices of the Government of Tigrai. The Government of Tigrai is also endeavoring to provide essential services including law and order, provision of electricity, rehabilitation of basic infrastructure, and other state functions in accordance with the law and normal practice. It is adhering to the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, which vests sovereignty in the nations, nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia, and not in the leader of the central government.

Calling the Government of Tigrai as the ‘TPLF’ and calling the TDF the ‘TPLF army’ is factually wrong. It is tantamount to calling the Government of Ethiopia as Prosperity Party and the ENDF as ‘Prosperity Army’. The TPLF doesn’t have an army in the same way that the PP doesn’t have one.

- Beware of the

trap of ‘legitimization’ of either or all of the parties

By definition, in a civil war, each party is contesting the legitimacy of the other. The UNSC naturally inclines towards respecting the authority of the government of the day, but it is unwise to award that government unconditional legitimacy.

To many Ethiopians, not only Prosperity Party’s legitimacy to rule, but its very legitimacy as a political party is contested. For others, including the regional government of Tigrai and other Ethiopian opposition forces, the legitimacy of the PP to rule ended on October 2020. Its controversial extension of its rule beyond October 2020 excusing the COVID pandemic was rejected by several political organizations in the country. The Government of Tigrai in defiance to the what it called an ‘illegitimate extension of the power’ of the Federal government held regional elections on September 2020. More than 2.7 million Tigraians voted in the elections for the regional house of representatives, the highest political body in the region and subsequently formed their government with a renewed mandate.

The Federal Government not only outlawed the Tigrai elections and the government formed through it but also began taking various measures to isolate the “illegal’ government and force the region succumb to the orders of the Federal Government. It not only began cutting government budgets but also among other things did cut a donor funded safety net program aimed at alleviating poverty. This tension eventually led the Federal Government to wage war against Tigrai in November 2020.

From the discussions above one can see that the ‘legitimacy’ of both the Federal Government and the Government of Tigrai are contested.

The African Union has already made the error of legitimizing Abiy’s regime through the declaration of the head of its observer mission H.E. Olusegun Obasanjo. AU’s legitimization of the June elections and its choice of the very same individual who championed this decision to be the candidate for mediating the conflict is a problem more than a question of mere partiality. Its affirmation to legitimize a corrupt political process is indicative of its readiness to countenance strategies of political management in the future. The UNSC should not repeat the same mistake.

The UNSC in its deliberations should at least not involve itself in this politics of ‘legitimacy’ but instead focus on issues of real politics. One of the important issues every international organization concerned with the crisis in Ethiopia raises is the need for an all-inclusive national dialogue for charting the future of a peaceful and prosperous Ethiopia. Many are concerned about the maintaining the unity and territorial integrity of Ethiopia without realizing that for all practical purposes Ethiopia is internally broken and caught in a civil war. For the Tigraians the Federal Government has tried to mobilize from all rest of the Ethiopian regions, aligned itself with the Eritrean Defense Forces and other external forces to eliminate them from the face of the earth.

If at all it is possible, the Tigraians are ready to give it a chance among other things by taking part in an all-inclusive dialogue. The UNSC and the world should at large must be clear that the Ethiopian government is not competent to organize and lead such an experiment. Any attempt to task and legitimize the government lead and run such an all-inclusive dialogue is dead before it even starts. The design, organization, and leadership for such a forum should be part of the negotiation for political settlement.

- Redeployment of

forces should follow the progress of the political process

The war that started in Tigrai has now operationally expanded to several parts of the Amhara and the Afar regions. Several resolutions of the US government and the European Union were passed demanding the cessation of hostilities and the redeployment of forces to their pre-November 2020 positions. Most recently a redeployment of the TDF to pre-November 2020 military positions in return for the opening of access routes for Humanitarian operations by the Ethiopian government is being proposed by some, including the AU.

The first problem with such a proposition is its attempt to implicitly or explicitly link the provision of humanitarian assistance to Tigrai with a ceasefire. The obligation on the belligerent parties to respect International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is not conditional on a ceasefire. Humanitarian aid should flow no matter what; rape and sexual violence are prohibited under all circumstances; and civilians should be protected regardless of whether there is ongoing

war. For these reasons ceasefire and associated redeployment of forces should not be linked to the opening of the routes for humanitarian operations.

The second problem with this proposition is its failure in fully understanding the driving reasons for the advance of the TDF operations into the Amhara and Afar regions. The advance was necessary not only for its need to open the Djibouti-Semera-Mekelle route for humanitarian operations but also to end the siege on Tigrai for good and to force the Amhara militia and the Eritrean Defense Force out of Tigrai to their pre-November 2020 positions. The TDF’s advance is also necessitated such that the full accountability and guarantee for the genocidal war is secured. Redeployment of the TDF to Tigrai without securing the complete liberation of Tigrai from the occupying forces and guarantees for non-occurrence of renewed aggression is unthinkable.

To this extend one can think of a three phased peace process towards a complete political settlement. Phase one is immediate actions which includes: the immediate suspension of hostilities for the limited purpose of unimpeded humanitarian access; restoration of essential services, withdrawal of Eritrean forces and Amhara militia from Tigrai; end of hostile propaganda and incitement of violence; and, the release of political prisoners as an essential pre-condition for negotiations. Phase two then follows including direct negotiations towards a permanent cease fire done directly between the federal government and the regional administration of Tigrai which negotiates key principles, key actions, time lines etc., for a complete political settlement. Phase three is an all-inclusive national political dialogue for a complete and national level political settlement.

- Issues related with disarmament and

arms control

The war thus far has ended in creating two conventional armies. The TDF has captured large amount of arms in the course of the war in the past ten months. It not only armed itself with mechanized war machinery that includes tanks, howitzers, and armored vehicles but also missile systems. The TDF did not exist prior to this war: it was created in response to the imposition of the war. It is now fighting for the full realization of the right of the people of Tigrai for self-determination including and up to secession. In doing this, it wants to make sure that any repeat of the current genocidal war is impossible.

The Government of Tigrai and its army realizes that Abiy’s government has broken the unity of this country. It is not against trying to mend the broken unity of the country, though it realizes it is a huge undertaking for all stakeholders. It believes that there should be some sort of transitional time whereby the reconstruction, accountability of crimes, and a national dialogue for a complete political settlement is completed. It is therefore impossible to talk about disarmament until such time the end of the transition and its results determine the fate of the TDF. One can only talk about arms control and management.

In summary, the UNSC in its future attempts for a resolution in Tigrai should review and take lessons from its past mistakes and particularly its resolution 2216 (2015) on Yemen. The war on Tigrai is a genocidal war. Tigraians are fighting for their survival as a people. Tens of thousands of innocent civilians have been killed through violence and starvation and heinous crimes including mass rape and all forms of war crimes are committed. Tigraians from all walks of life no matter their political, religious, and all other forms of differences have mobilized themselves under the umbrella of the TDF to fight for their survival. Attempts to deal with the war in Tigrai need to realize this and be designed with care and responsibility.