Three years after the Ethio-Eritrean war against Tigray was launched, and one year after the Pretoria Permanent Cessation of Hostilities Agreement brought active conflict to an end, there are rumors of a new war. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been speaking about Ethiopia’s need for a port, and he is threatening to invade Eritrea.

Despite his love for hi-tech, Abiy won’t be able to fight a war by drones alone. If Ethiopia’s federal forces go to war against Eritrea, they will need Tigray on their side, as a full member of a fighting coalition. The Tigray region is strategically positioned next to the Eritrean highlands and the Tigrayan Defense Forces are a formidable army.

Some Tigrayans might consider that they have sufficient reason to go to war. It would be an opportunity to drive Eritrea out of the large Tigrayan territories it still occupies. Tigray could insist on the overdue return of Western Tigray as a precondition. Some Tigrayans would want revenge for the atrocities that the Eritrean soldiers committed—and continue to commit—against Tigrayan civilians. And Tigrayans might also calculate that Abiy may go to war anyway, and they will not be able to escape the fighting.

But the costs and risks of a new war far outweigh those considerations. A few weeks after the Tigrayans collectively mourned the deaths of 51,700 members of the defense forces in the last war, the prospect of sending more young people to die is unconscionable. Tigray is exhausted. A year on from the truce, people remain hungry. Little aid is trickling in. Another war would plunge Ethiopia deeper into economic crisis, from which Tigray cannot possibly benefit.

The answer to Tigray’s woes is to implement the Pretoria Agreement. The African Union, which convened the talks and proclaimed the agreement as a triumph, has yet to report on its obligations for monitoring and implementation. The international donors who lined up to applaud the agreement have not made assistance to Ethiopia conditional on full implementation of the key provisions of the deal, such as a return to the constitutional order. Nor, for that matter, did they suspend assistance when Abiy launched another war in Amhara region.

Too many people have died, too much wealth has been destroyed. Tigray should refuse to play Abiy’s bellicose games, just as the African Union and international donors should stop appeasing a serial warmonger.

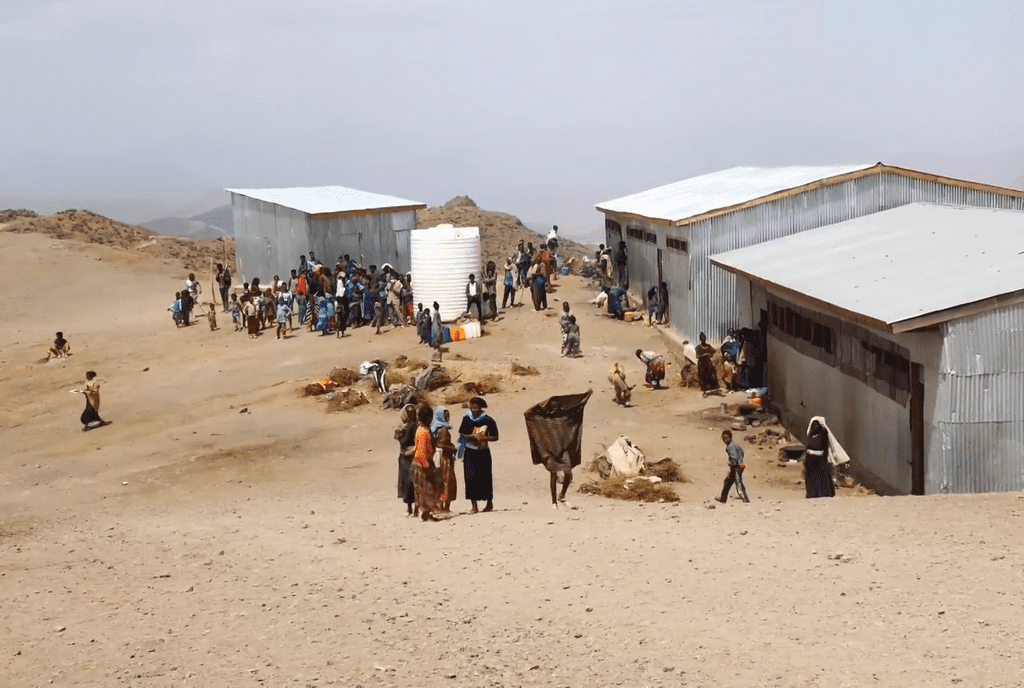

Photo: A destroyed armored vehicle in one of the main streets of Hawzen, Yan Boechat/VOA (Public Domain)